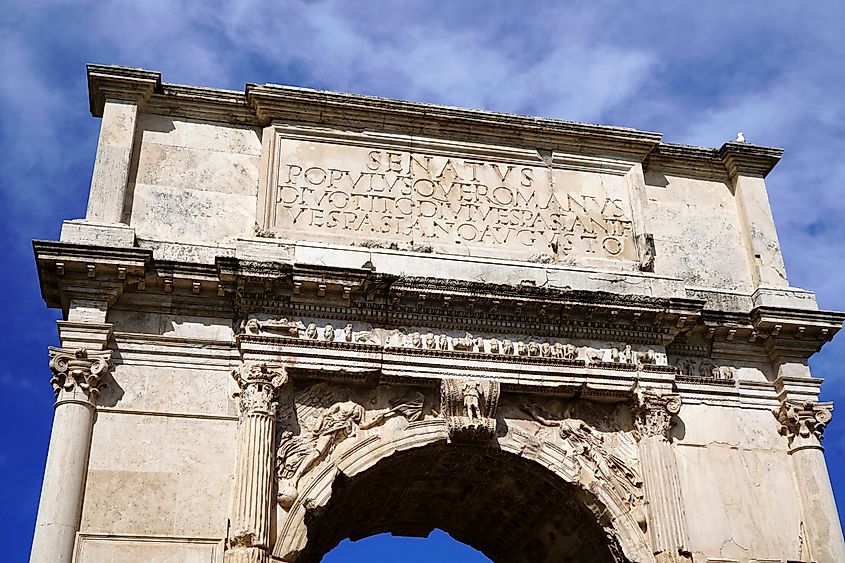

The Demise of the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate was the beating heart of the Roman Republic and its political machinations for centuries. At the time, it was arguably the most robust political organization in the world. It oversaw Rome's transformation from a small city-state to a vast empire across three different continents.

While the Senate would lose much of its powers that it once had during the years of the Republic, the Senate during the years of the Roman Empire and even after Rome's collapse still had a significant impact on the day-to-day life throughout Roman-held territory.

The Origins Of The Senate

Rome was ruled as a monarchy between 753 BC and 509 BC. During this time, the groundwork for the Senate was first put into motion. While the function of the Senate was much different in the years of the Republic, the Senate during the Roman Monarchy played more of an advisory role to the king.

Within this Senate, there was still a clear distinction of rank between its members. The members were made up of lesser and greater families, with the larger families usually set apart by their wealth and prestigious military victories, who held the lion's share of power and influence. While the king ultimately made the final decision on all political matters, he was still beholden to the Senate as all of its members belonged to the wealthy land-owning elites of Roman society, often referred to as Patricians. The Senate at this time was exclusively made up of the Patrician class.

The Roman Monarchy came to an end when the final Roman king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, was overthrown in a revolt. Lucius was regarded as a ruthless tyrant by most Romans, particularly when he had several senators put to death after calling their loyalty into question. When Lucius was deposed, the Roman Republic was established in 509 BC with the explicit aim of safeguarding against the pitfalls and shortcomings that were so prevalent during the years of the monarchy.

The Golden Age Of The Roman Senate

During the Roman Republic, the Senate reached its height in power and influence over Roman society. The senator was never elected at this time but was instead appointed by the consuls, the highest ranking member of the Senate. Consuls were elected from within the Senate itself and were only permitted to serve for one year at a time. In nearly all cases, a second consul would rule simultaneously in hopes that both consuls would keep one another in check. After their term as consul had ended, they rejoined the Senate, and another consul was elected. While the position of consul was only temporary, senators served for life. Consuls almost always appealed to the Senate when it came to passing laws and other policies, as they knew angering the Senate could mean political suicide after their time as consul ended.

The Senate did allow for the appointment of a dictator during times of crisis. This dictator was given absolute power but was expected to surrender the emergency powers when their role was no longer needed. The most famous instance of this occurred in 458 BC when Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, a Roman statesman who had since retired from his political career to become a farmer, was given the office of dictator to rescue a Roman army at war with a rival city. According to legend, Cincinnatus crushed the enemy forces and won the war for Rome. Afterward, he gladly gave up his powers and returned to his simple life on his estate. Cincinnatus was forever held up as a moral example of the ideal Roman citizen who selflessly answered his civic duty for the good of the Republic.

A Slow Decline Into Empire

The Senate became considerably more powerful in 312 BC when the censors, a position within the Senate, could control who joined the Senate rather than the elected consuls. This radically increased the power of the general body of the Senate and resulted in intense factionalism within the Roman government.

As Rome expanded outwards through its many conquests, military generals started to rise in power that often exceeded that of the Senate. There were many such cases when the Senate would issue commands to generals only for the generals to completely disregard their orders. Ultimately, true power in the Late Roman Republic was held by the Legions rather than the Senate. This became abundantly true during the time of Julius Caesar. Caesar, who had gained considerable power and prestige by conquering Gaul (modern-day France) marched on Rome and after vanquishing his political adversaries he declared himself dictator. Caesar then grew the number of senators to 900, most of these new positions were filled with his allies.

Caesar was famously killed on the Senate floor by his enemies which plunged the Republic into another brutal civil war. When the dust settled, Augustus, Caesar's adopted son, emerged victorious. While officially fighting to reinstate the Republic, he effectively ruled with absolute power and became Rome's first emperor.

The Senate During The Empire

The Senate throughout the Roman Empire still held moderate power, but was second to the emperor's. The Senate was responsible for governing Rome and the province of Italy. Their power was also extended to rule over provinces that did not require a direct military presence, but that was uncommon due to the nature of the Roman Empire.

The Roman Emperor was now the only person who could elect and remove senators. The Senate also lost all of its power regarding the treasury and foreign policy. While the Senate could still lend advice and bring issues to the attention of the emperor, its true power was a shadow of its former self. Senators eventually lost their rights to lead armies in battle for fear that they would challenge the imperial throne should they become too successful. Towards the end of the Roman Empire, the number of senators rose to around 2,000 and were often made up of quasi-feudal lords who ruled over large farming estates mostly dependent on slave labor.

While the Senate did not hold much legislative power during the time of the Roman Empire, it was still made up of wealthy landowners who held sway in day-to-day life within Rome. Even though the institution of the Senate had been defanged, numerous Roman Emperors were assassinated thanks to the political scheming of groups of ambitious senators.

The End Of The Roman Senate

Rome ended in 476 AD after it was sacked and occupied by the Ostrogothic King Odoacer. Contrary to popular belief, Odoacer and his predecessors surprisingly respected Roman tradition and likely saw themselves as an extension of Roman rulers rather than outright foreign conquerors. They attempted to repair Rome's crumbling infrastructure and derelict neighborhoods. The Ostrogoths also made a considerable effort to try to assimilate into the previous Roman political framework, and this can be seen in the preservation of the Roman Senate.

While it is unlikely that the Roman Senate under Ostrogothic rule played an almost identical role as it had during the days of the Empire, the fact that it was not destroyed paints a very different picture of these new rulers. The last mention of the Roman Senate occurred in 580 AD. The exact fate of the Roman Senate remains a mystery. Ironically, it is most likely that the Senate was abolished by the Eastern Romans (Byzantines) shortly after they retook Rome from the Ostrogoths in the middle of the 6th century.

The history of the Roman Senate is as long as Rome itself. Despite its power being severely reduced during the time of the Roman Empire, it still remained a formidable political organization for centuries. Even centuries after it faded away from the historical record, the Roman Senate and its legacy remain the basis for dozens of governments in the modern age.