The War of Alexander's Successors

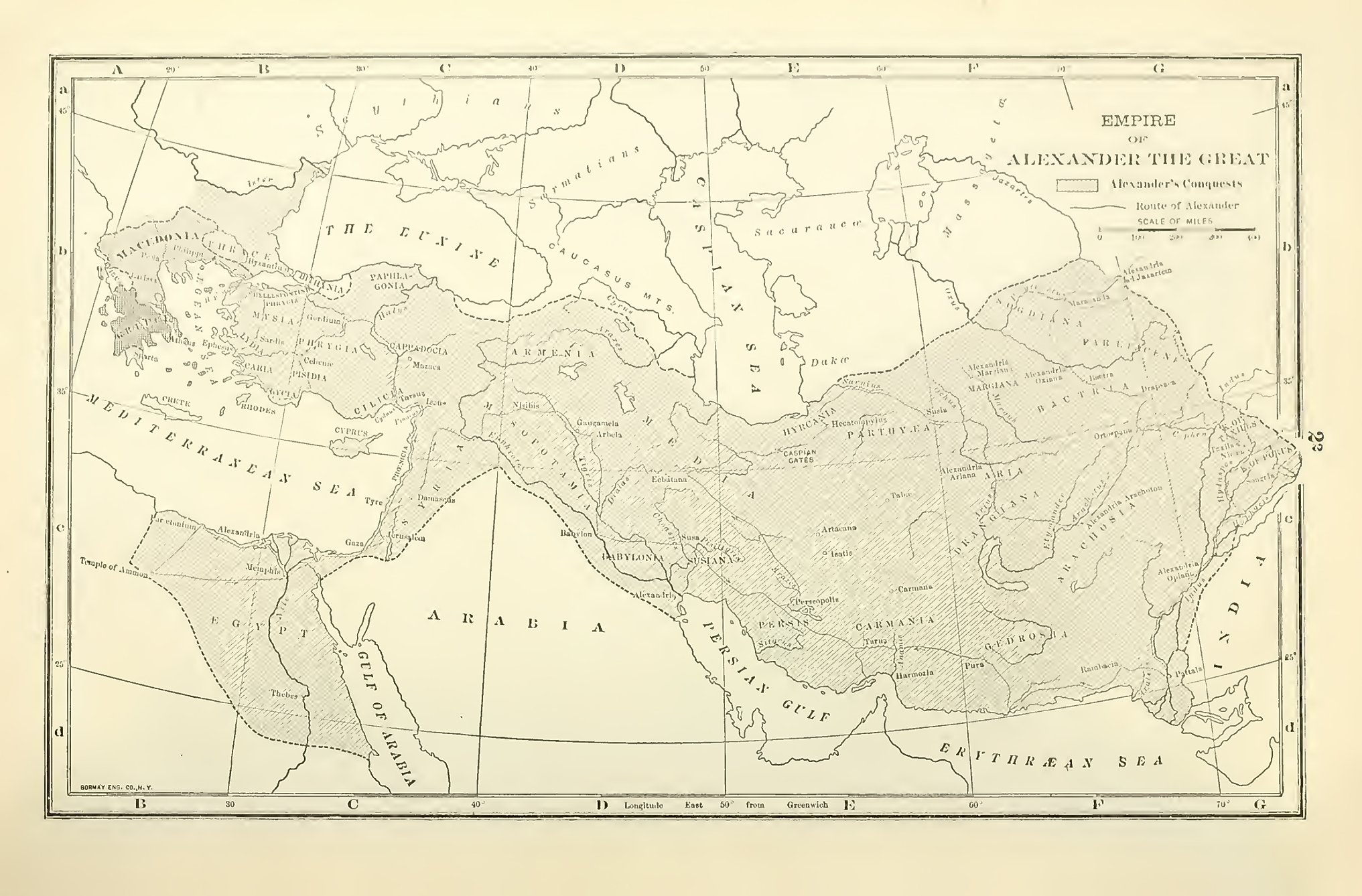

The demise of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE precipitated a tumultuous and extended conflict for control of his expansive empire. This struggle, known as the War of Alexander's Successors, unfolded over several decades, profoundly shaping the geopolitical landscape of the ancient world. Alexander's sudden death left a vast empire, stretching from Greece to Egypt and deep into the heart of Asia, without a clear heir. The ensuing power vacuum ignited a series of conflicts among his generals, the Diadochi, as they vied to carve out realms from the sprawling Macedonian Empire. This essay explores the intricate web of military engagements, political intrigues, and cultural transformations that marked the War of Alexander's Successors, delving into the events that fragmented an empire and gave birth to the Hellenistic Age.

The Struggle for Power: Initial Conflicts

The immediate aftermath of Alexander’s death saw his empire at a crossroads, with numerous generals and satraps positioning themselves for power. The Partition of Babylon in 323 BCE, a council held to settle the empire’s fate, established a framework for sharing power, yet it was hardly a solution to the brewing storm. Key figures emerged in this initial struggle: Perdiccas, Ptolemy I Soter, Antigonus, Seleucus, and Lysimachus, each commanding significant military and administrative resources.

Initial conflicts centered around the guardianship of Alexander's half-brother Philip III Arrhidaeus and his infant son Alexander IV. Perdiccas, appointed as regent, sought to maintain a united empire, but his authority was contested. The first series of battles and political maneuvers revealed the ambitions and capabilities of the Diadochi. The initial period was marked by shifting alliances and sudden betrayals, as each successor sought to strengthen their position.

Ptolemy's appropriation of Alexander's body, diverting it to Egypt, was a symbolic move that demonstrated his intent to establish an independent rule. The subsequent wars, including the First War of the Diadochi (322-320 BCE), were characterized by complex military campaigns across Asia Minor, Egypt, and the eastern provinces. Perdiccas's failed Egyptian campaign in 321 BCE and his assassination marked a significant turning point, leading to the Partition of Triparadisus and a realignment of power among the successors.

Key Battles and Turning Points

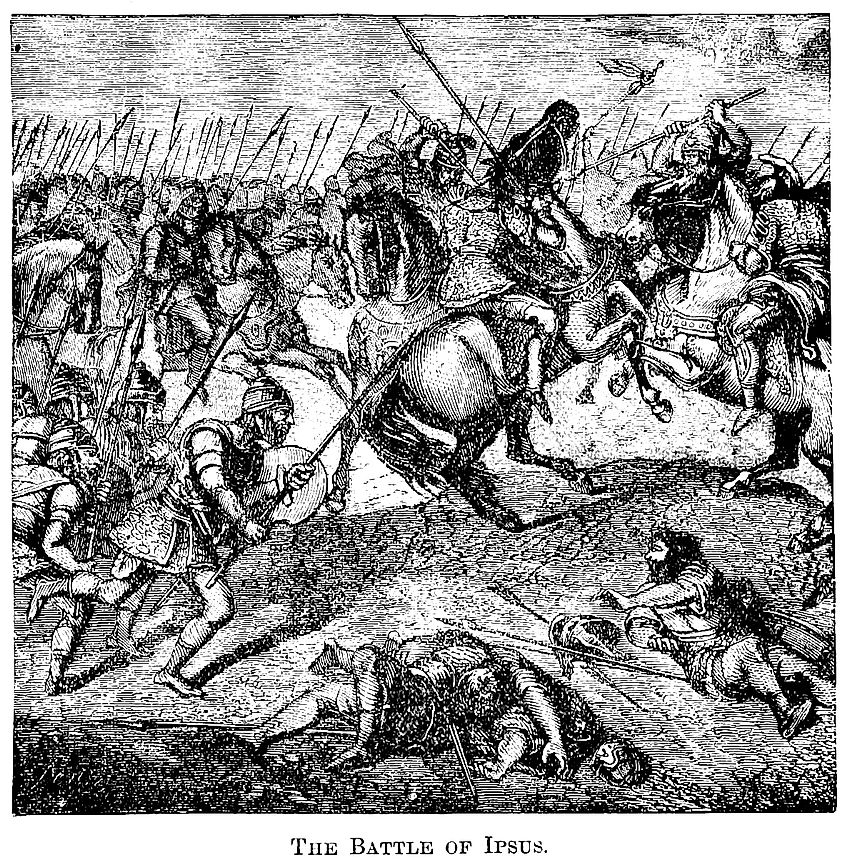

The ensuing conflicts were marked by several decisive battles that reshaped the landscape of the Hellenistic world. The Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE can well represent the turning point. Fought in Phrygia, in present-day Turkey, this battle saw the coalition of Seleucus, Lysimachus, and Cassander clash with the forces of Antigonus Monophthalmus and his son Demetrius. The victory of Seleucus and Lysimachus not only led to the death of Antigonus but also arguably ended the dream of reuniting Alexander's empire under a single ruler.

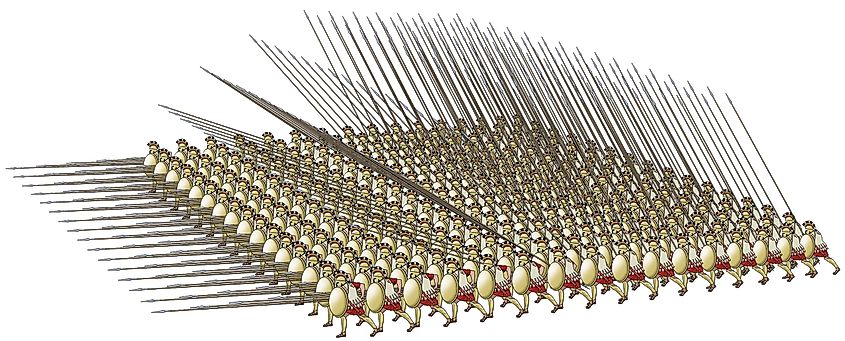

The tactics and strategies employed during these battles were diverse, reflecting the military genius of Alexander's former generals. From the use of phalanxes and cavalry to innovative siege techniques, the Diadochi demonstrated a profound understanding of warfare. The Battle of Ipsus, in particular, was notable for the use of war elephants, which Seleucus had acquired from the Indian king Chandragupta Maurya.

This period also saw the emergence of new power centers. Seleucus established the Seleucid Empire, encompassing much of Alexander’s Asian territories. Ptolemy solidified his control over Egypt, founding the Ptolemaic Dynasty. Lysimachus and Cassander carved out realms in Thrace and Macedon, respectively.

Political Betrayal and Diplomacy

The war of Alexander’s successors was not merely a series of military confrontations but also a chessboard of political machinations. The Diadochi were adept at forging and breaking alliances, marrying into each other's families, and engaging in diplomatic negotiations to achieve their aims. The intricate web of alliances and enmities often shifted the balance of power, reflecting the fluid nature of political loyalty in this era.

Intrigue and betrayal were rampant, with notable instances such as the murder of Perdiccas by his own officers and the frequent double-crossings among the successors. The diplomatic exchanges were complex, involving the Diadochi and other powers like the Greek city-states and external kingdoms, which saw opportunities to expand their influence amidst the chaos.

The fragmentation of Alexander's empire into smaller, more manageable realms under individual rulers was a gradual but inevitable outcome of these political dynamics. Over time, the vision of a unified empire under Macedonian rule faded, giving way to a multipolar world where the successors ruled as monarchs over their respective territories.

Cultural and Administrative Impact

The Wars of the Diadochi did more than just redistribute territories; they fundamentally altered the cultural and administrative landscapes of the Hellenistic world. As the successors established their independent kingdoms, they brought with them elements of Macedonian and Greek culture, effectively spreading Hellenism across a vast expanse.

The new rulers established cities, many of which were named after themselves, such as Antioch (by Antigonus) and Alexandria in Egypt (by Ptolemy). These cities became centers of Greek culture, language, and learning, often blended with local traditions and customs. This fusion of cultures, known as Hellenization, led to significant developments in art, science, and philosophy. The Library of Alexandria, for instance, became a symbol of this cultural synthesis and intellectual prowess.

Administratively, the successors adopted and adapted Greek methods of governance while also respecting and utilizing local practices. They continued Alexander's practice of founding cities as administrative and military centers, which facilitated trade and economic growth. The integration of diverse regions under larger entities, such as the Seleucid and Ptolemaic empires, possibly contributed to a more interconnected economic system, enhancing trade routes that spanned from the Mediterranean to Asia.

Militarily, the Diadochi maintained the phalanx and other Macedonian innovations but also incorporated new elements, such as war elephants. Socially, the wars led to changes in class structures and power dynamics within the successor states. The creation of monarchies ruled by Macedonian elites in regions like Egypt and Persia marked a shift from the previous political systems.

The lasting impact of these changes can be seen in the persistence of Hellenistic culture long after the end of the Diadochi wars. The blend of Greek and local elements gave rise to a distinctive period in history that continued to influence subsequent civilizations.

Key Takeaways

The War of Alexander's Successors was more than a mere scramble for territory; it was a complex series of events that reshaped the ancient world. Through their ambition and prowess, the Diadochi fragmented Alexander's empire but also laid the foundations for the Hellenistic Age. Their actions led to the spread of Greek culture and ideas far beyond their native lands, influencing a wide array of regions and peoples.

The wars, while destructive and chaotic, facilitated the fusion of cultures and the spread of Hellenism, impacting art, science, governance, and society. Though eventually succumbing to Rome and other powers, the successor kingdoms left a lasting legacy that continued to shape the course of history long after their demise.