The World's Most Puzzling Ancient Disappearances

There’s nothing more fascinating than a cold case. In recent years, countless true crime podcasts and documentaries have taken advantage of our fascination with unsolved mysteries, but our shared love for speculating about the blanks on our map of the past goes much, much further back. Want proof? The stories of these eight mysterious disappearances in the ancient world have been passed down, speculated about, and discussed ad nauseum for centuries. From lost treasures to entire civilizations that vanished without a trace, these ancient cold cases continue to puzzle and fascinate scholars and dabblers alike. Let's examine the world's most puzzling ancient disappearances.

Lost Army of Cambyses

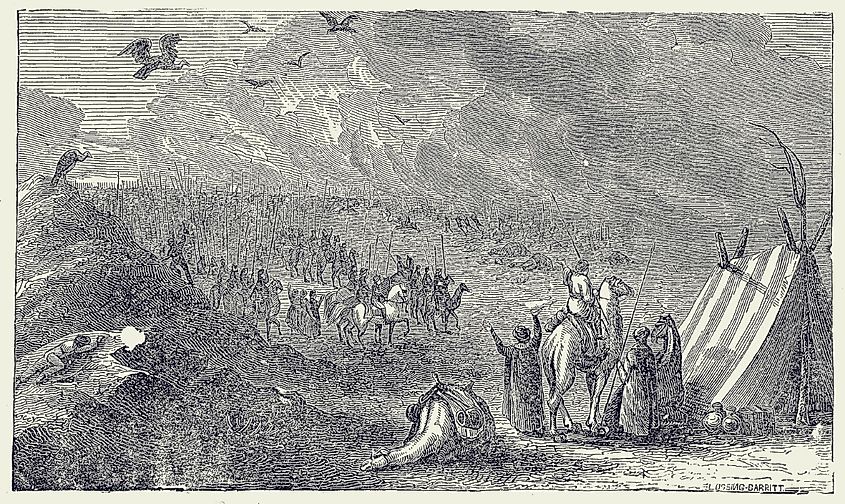

Many of ancient history’s unexplained disappearances are on a grand scale: whole cities abandoned without a trace, civilizations who disappear from the historical record suddenly and without explanation, and peoples who vanish, leaving behind only material proof of their existence. But the Lost Army of Cambyses is even more mysterious: a whole army, 50,000 strong, that set out for an engagement in Egypt from which they never returned.

According to the ancient historian Herodotus, the Lost Army of Camybses was a Persian military unit that had been sent by then-king Cambyses II in 525 BCE to suppress a revolt against Persian rule by followers of an Egyptian religious figure, the Oracle of Amon. But they never made it to their final destination; Herodotus wrote that the army was buried in a catastrophic sandstorm and never heard from again.

But Herodotus’ account has not gone unquestioned. There’s the lack of archeological evidence, for one thing: an army buried in a sandstorm would still be lying somewhere beneath the desert sand, and no such remains have ever been found. And there’s the sheer improbability of such a natural disaster to think of, too. As Egyptologist Olaf Kaper said of the story, “experience has long shown that you cannot die from a sandstorm,” and he’s not the first to wonder what else might have befallen them. Even so, no conclusive evidence has yet been found.

This lack of answers isn’t for lack of trying. Notably, a Harvard-sponsored 1983 expedition spent six months searching for the remains of the Lost Army on the Egypt-Libya border, but it turned up virtually nothing that could reasonably be connected to the Lost Army of Cambyses. Oil prospectors supposedly turned up artifacts that seemed contemporary with the Lost Army in 2000, but the site was never investigated any further. To this day, archaeologists have yet to find any answers, leaving the disappearance of the Lost Army of Cambyses shrouded in mystery.

Could this have been the work of a furious sandstorm? Perhaps. But lately, scholars have had a different idea: the Lost Army was not buried alive but rather defeated by an Egyptian rebel leader named Petubastis III. This theory stems from telling inscriptions on blocks used in temple construction that tie Petubastis III to the oasis where the Lost Army was heading when it “disappeared.” As such, these scholars posit that Petubastis III, not the Oracle of Amon, was the true target of their military campaign — and that his forces came out on top in the ensuing battle. When later Persian king Darius the Great vanquished Petubastis to retake control of Egypt, these scholars argue that the cover story of a killer sandstorm spread as a way to erase their army’s embarrassing earlier defeat by the Egyptians.

While answers remain elusive in the case of the Lost Army of Cambyses, the latest developments excitingly imply that this so-called history might actually be the work of ancient spin doctors. Archaeological evidence that Petubastis III was the real target of the Lost Army would strongly indicate that Herodotus’ sandstorm story was Persian propaganda. And that would make the legend of the Lost Army a revealing example of the internal practices that helped the Persian Empire’s leaders centralize and retain their power.

Indus River Valley Civilization

If you had to take a world history class in school, there’s a good chance you read about the Indus River Valley Civilization. Dating back to roughly 3300 BCE, this five-thousand-year-old culture is one of the first major civilizations we know of. Its people’s accomplishments included the creation of their own system of writing, the implementation of sophisticated sewage and irrigation systems, and participation in long-distance trade. But in about 2500 BCE (some experts argue it was closer to 2000 BCE), the Indus River Valley Civilization began to decline.

Its peak population of roughly 60,000 began to dwindle as people migrated from major urban centers to decentralized villages. Its cities, some of the world’s largest and among the earliest major cities in world history, were soon abandoned. And we have no archaeological evidence that any of the smaller villages that succeeded them were still inhabited by 1300 BCE. So how did one of the world’s great early civilizations simply disappear? Scholars have posited a few theories, but the short answer is that we just don’t know.

The prevailing theory at present is that climate change made the large urban centers that defined early Indus River Valley civilization unviable. The Saraswati River began to dry in 1900 BCE, a date coinciding roughly with the decline of major cities like Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro. It has been suggested that summer monsoon cycles also played a role: the intensity of these annual rains in the Indus River Valley began to decline around 2500 BCE as well, and they may have forced the primarily agricultural civilization to abandon its cities in favor of areas where monsoons were more abundant and could support farming.

Though it’s also been suggested that an invading Indo-European tribe wiped out the Indus River Valley civilization, modern archaeological evidence doesn’t widely support that theory. Instead, contemporary scholars largely agree that the Indus River Valley people simply dispersed and dwindled gradually in numbers as climatological factors made their prior way of life unsustainable. Though elements of their culture are seen in later civilizations on the Indian subcontinent, many of the innovations this early society have resultingly been lost forever.

Legio IX Hispana

It took a lot to stand out as a military unit among the legions of the ultra-militaristic Roman Empire, but the Legio IX Hispana — the Ninth Spanish Legion in English — did just that. These elite Roman soldiers served in Julius Caesar’s Gallic campaigns, the Cantabrian Wars in Spain (from which they took their contemporary name), and the invasion of Britain in 43 CE. They survived multiple mutinies and near-total defeats to participate in almost every notable Roman campaign before its disappearance in or around 120 CE. So what exactly finally felled this storied unit?

Several theories have been proposed. The prevailing one at present is that they simply met their match during their skirmishes with the Caledonian people of Scotland in 122 CE. It’s often suggested that they acted dishonorably in their engagements with the Caledonians and were stripped of their status, leading historians to skip over them when retelling the history of the conflict. But others cite surviving soldiers who went on to be recorded in connection with future conflicts to suggest that their final defeat came much later. Proponents of other theories suggest that the Ninth Legion met its end during the Second Jewish Revolt in 132 CE or in battle with the Parthians in 161 CE.

However, military history of this period is muddled and exceedingly difficult to track when gaps in the record appear, making it unlikely that the reason for the disappearance of the Ninth Legion will ever be conclusively known. Because the Romans were faithful chroniclers of their own history, the so-called legend of the so-called “Lost Legion” presents a tantalizing mystery that reminds us that there will always be gaps in our knowledge of the past.

Minoans

When we think about “the ancient Greeks” today, we’re thinking about several successive civilizations that contributed to the culture we now recognize. One of the first of those civilizations sprung up on the island of Crete in about 3000 BCE. The Minoans — whose name is now most recognizable in the name of a legendary Greek monster, the minotaur — had a flourishing civilization that weighed heavily in Mediterranean trade and seafaring despite its small size. Its advanced infrastructure and architecture speak to a prosperous culture that enjoyed great success in its day. But around 1450 BCE, that all came to a screeching halt. Why?

Once again, natural disaster is a popular theory. In 1500 BCE, a volcano eruption on nearby Santorini may have sent tsunamis hurtling towards the shores of Crete or disrupted weather patterns in the region. Its follow-up fifty years later could’ve done even more damage. Alternately, some scholars believe that invasion brought the Minoans to their demise. And still others believe that the Minoan civilization may have begun to falter when natural disasters and political tensions disrupted its prosperous maritime trade, eventually falling into obscurity and fading away once it was no longer able to control key Mediterranean trade routes.

Though the Minoan culture’s sudden decline is shocking, one only has to look at the area’s turbulent tectonic past and the Minoans’ heavily trade-based economy to see a variety of ways that it might have come about. Though the exact details of the decline and fall of the Minoans aren’t known, what we do know is that their sudden decline didn’t keep their highly advanced culture from profoundly impacting later Mediterranean people.

Olmecs

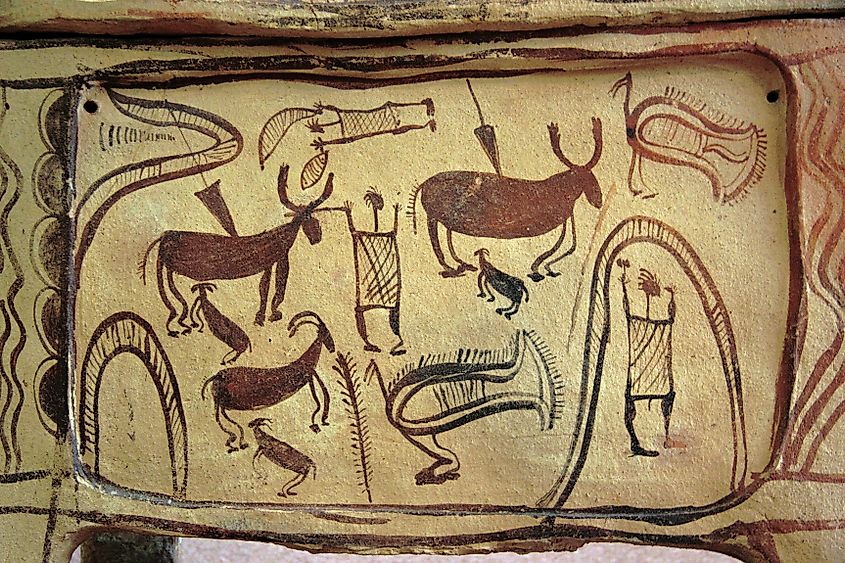

Some historical mysteries are documented in ancient texts: we know the Lost Army of Cambyses from the writings of Herodotus, and the Ninth Legion from the fastidious record-keeping of the Roman army. But other civilizations left behind solely material evidence of their ways of life, and the Olmecs of Mexico are one of those cultures. That means that all we know of their culture — and its mysterious disappearance — comes from the archeological evidence that researchers in the region have uncovered.

The Olmecs made their home in southern Mexico from roughly 1200 BCE to 500 BCE, and archaeological evidence has revealed that they were a primarily agricultural society. They’re probably best-known today for the massive stone heads they carved, statues whose purpose is not yet known. They paved the way for future Mesoamerican civilizations: for example, a ball game invented by the Olmecs was played by later cultures in the region and remained culturally significant for centuries after their decline. But the chain of material evidence for their continued activity in the region abruptly ends around 400 BCE. Why is that?

Based on damage to Olmec monuments at the key site of San Lorenzo, many archaeologists have speculated that armed conflict played a role. Invasion or internal revolt might have been catastrophic to the Olmec culture. Natural disaster may also have explained the decline: volcanism in the nearby Tuxtla Mountains might have altered the course of the region’s rivers, which would have stripped the Olmec cities of a lifeline.

However, it’s highly unlikely that the Olmec people totally disappeared; if that had been the case, they couldn’t have passed on aspects of their culture that are clearly seen in later civilizations.

Zannanza

It’s not every missing person case that’s remembered for thousands of years. In fact, this one is the oldest in recorded history: in 1324 BCE, the Hittite prince Zannanza was sent to Egypt to marry an Egyptian princess and vanished without a trace. His disappearance sparked conflict between the two empires, and it remains unknown what became of the unfortunate prince.

Zannanza’s troubles began when the recently widowed queen of Egypt requested that Suppiluliuma I, then ruler of the Hittite Empire, send her one of his sons as a husband. This aroused suspicion due to the tendency of Egyptian royalty to marry within their own country, but Suppiluliuma eventually acquiesced, hopeful that putting his son on the Egyptian throne would give him leverage with which to conquer the rival empire.

But when Zannanza failed to appear in Egypt, Suppiluliuma’s initial suspicions seemed like they may have been founded. Accusations of murder were quickly levied, armed skirmishes broke out, and an epidemic brought from Egypt by prisoners of war eventually killed Suppiluliuma himself. And as for Zannanza, nobody ever got to the bottom of his disappearance.

Both then and now, many believed that the eventual king of Egypt, Ay, had Zannanza assassinated before he reached Egypt. But as there’s virtually no chance that any concrete evidence for this theory will emerge, Zannanza’s 3,000-year-old case remains cold.

Çatalhöyük

One of the world’s oldest cities is a major outlier. Located in the Anatolian region of modern-day Turkey, the Neolithic settlement of Catalhoyuk is over 9,000 years and may have had as many as 8,000 residents. It’s a very early example of the settlements that the dawn of agriculture allowed people to begin building, located temporally at a historical node when a nomadic way of life was beginning to give way to a settled agricultural lifestyle. There’s nothing else like it in the world of archaeology, which makes its abandonment in roughly 5950 BCE all the more mysterious.

However, modern archaeology is pointing to surprisingly modern problems as probable causes of the city’s downfall. Skeletons of inhabitants with signs of human-inflicted injuries have been found. Teeth of those skeletons have demonstrated an overall decline in health over the centuries that Catalhoyuk was inhabited. And the city’s extremely high population density could very well have led to both outbreaks of violence and the rapid spread of disease, and agriculture could have impacted their diets nutritionally for the worse.

We don’t know if this declining quality of life really spelled the doom of the city of Catalhoyuk, but it’s highly possible that it was a contributing factor. And it’s a powerful ancient cautionary tale: although bringing humans together on a large scale has allowed us to be more efficient, productive, and prosperous, there are trade-offs to a centralized urban lifestyle that can’t be ignored.

Clovis People

In school, many of us learned that the first inhabitants of the Americas migrated across the Bering Land Bridge from Siberia during the Ice Age. But less of us learned about the first of those people that archaeologists have found and studied in-depth: the Clovis people, named for the New Mexico town where archaeologists first discovered stone tools that provided the initial evidence of their existence. They’re one of the oldest cultures in the Americas, and their mysterious disappearance from the archaeological record is one of the greatest mysteries of the ancient world.

Over 15,000 years ago, the predecessors of the Clovis People — actually several unrelated groups — settled in North America, creating stone tools and spreading across the continent until evidence of their existence abruptly disappeared about 12,750 years ago. Why? It’s likely that the rapid climate change of the Ice Age made it impossible for their subsistence hunting lifestyle to continue, forcing them to migrate south.

Archaeologists have come to believe this because North America’s megafauna — prehistoric mammals like mammoths and mastodons — became extinct around the time that the Clovis people stopped leaving behind material goods. It’s been proposed that the extinction of these species may have factored into the sudden decline in Clovis cultural artifacts seen by archaeologists.

Although ancient disappearances tend to attract scholarly interest, the fact remains that much of the evidence that could have solved them is lost to time. With nothing to go by but written and archaeological records of long-ago events, we’re left to piece together sources that don’t always fit, and the odds of finding a conclusive answer are very low. But perhaps that’s for the best: without the excitement of a mystery to solve, it’s doubtful that archaeologists and historians would have gone out in search of answers and come away with unexpected but equally valuable discoveries.