Are There Panthers In Florida?

In the stillness of a balmy Florida dusk, a hiker in the Big Cypress National Preserve once caught sight of a sleek, tawny form silently weaving through palmetto scrub. Startled yet fascinated, they wondered: Was that really a panther?

For centuries, stories of large cats roaming the Sunshine State have sparked curiosity and debate. The question still arises today—do panthers really exist in Florida? The short answer is yes, but the long story behind the Florida panther (Puma concolor coryi) is one of survival against daunting odds.

What's A Panther? Terminology and Misconceptions

Panther vs. Cougar vs. Puma

"Panther," "cougar," "puma," and even "mountain lion" are all common names used for Puma concolor, a large cat species native to the Americas. Although the word "panther" may evoke images of black leopards or jaguars in distant jungles, in North America it typically refers to the cougar. This name confusion often leads to misunderstandings. In the southeastern United States, when people talk about “panthers,” they are almost always referencing the local population of cougars.

Florida Panther: A Subspecies

The Florida panther is a recognized subspecies of cougar, scientifically known as Puma concolor coryi. It is distinguished by certain physical and genetic traits, including a tendency toward a smaller overall size and a characteristic crook in the tail. Evolving in the subtropical swamps and forests of Florida, this subspecies is uniquely adapted to its humid, water-rich habitat. Genetic studies suggest that Florida panthers were once part of a larger cougar population spread across the southeastern U.S., but today, they remain isolated in a shrinking range primarily in southwestern Florida.

Misidentifications and Rumors

Florida’s sprawling suburbs and thick natural areas can confuse even the keenest observer. Other animals—like bobcats, feral dogs, or even large domestic cats—are sometimes mistaken for panthers, fueling rumors. Urban legends about "black panthers" roaming golf courses or backyards persist, despite a lack of verifiable evidence. Such misidentifications make it difficult to separate folklore from legitimate sightings.

Historical Presence of Panthers in Florida

Pre-Colonial Times

Long before European contact, indigenous peoples in Florida hunted alongside—or sometimes fell prey to—large cats akin to today’s Florida panthers. Archeological remains and tribal lore suggest that these predators once roamed across much of the southeastern United States, thriving in forested wetlands and grasslands. Florida’s subtropical climate, abundant deer (before deer hide trade came into the scene,) and vast wilderness areas offered a near-ideal ecosystem for these apex predators.

Population Decline and Causes

With the arrival of European settlers, large swaths of Florida’s wilderness were converted into farmland and urban centers. Panthers were hunted aggressively—sometimes under government-sponsored bounty programs—due to fears of livestock predation. By the early 20th century, extensive habitat loss, hunting, and fragmentation of wild lands had decimated panther populations. Panther sightings plummeted, and the species appeared perilously close to extinction in Florida by the mid-1900s.

Legislative Milestones and Protection

Recognizing the dire situation, conservationists and scientists began to advocate for legal protections. The Florida panther was listed as an endangered species in 1967, before the Endangered Species Act (ESA) was formalized in 1973. Federal and state agencies then initiated recovery efforts, including habitat protection and research programs, establishing the panther’s endangered status as a priority for wildlife management.

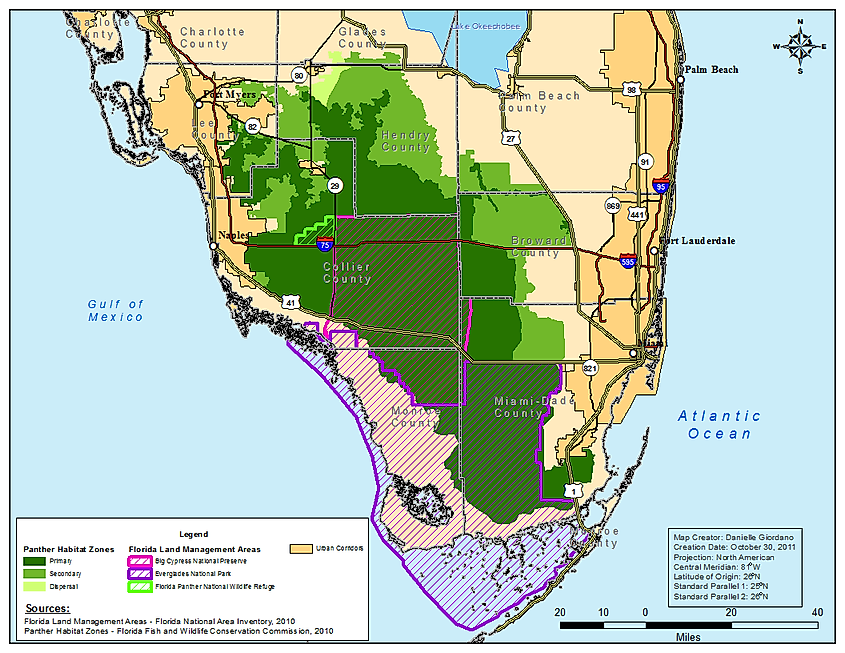

Current Panther Range and Habitat

Today, Florida panthers predominantly inhabit the southwestern portion of the state, with a core population centered around Big Cypress National Preserve, Everglades National Park, and nearby private lands. Historically, these cats ranged across the southeastern United States, from Arkansas to the tip of Florida. Urban development and the expansion of roads have significantly shrunk their roaming areas.

Florida panthers require large territories filled with dense vegetation, where they can stalk prey and rest unseen. Their primary food sources are white-tailed deer and wild hogs, supplemented by smaller animals when necessary. Adequate water sources and natural corridors that connect different patches of wilderness are essential for migration, breeding, and maintaining genetic diversity. Roads and residential areas that fragment these corridors pose a major threat to their survival.

Typically nocturnal or crepuscular, Florida panthers do much of their hunting at dawn or dusk, relying on stealth and acute senses. They stalk their quarry, often pouncing at close range.

Population Status and Conservation Efforts

According to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC), the Florida panther population hovers around 120 to 230 adult individuals. While this is an improvement over the mid-1990s—when the number was estimated at fewer than 30—these cats remain one of the most endangered mammals in the United States. Conservationists closely monitor births, deaths, and genetic health to gauge the population’s trajectory.

One of the pivotal steps in rescuing the Florida panther was a genetic restoration project in the 1990s. A handful of female Texas cougars (Puma concolor stanleyana) were introduced into South Florida to breed with the inbred panther population. The infusion of new genes strengthened kitten survival rates and reduced genetic defects. While considered a success, the project stirred debate among purists concerned about diluting the Florida panther’s distinct traits. Nonetheless, most biologists agree that without genetic restoration, the Florida panther might have vanished.

Federal and state agencies, alongside nonprofits, have prioritized habitat preservation to allow the population room to expand. Conservation easements, land purchases, and wildlife corridor projects seek to protect and connect essential panther habitats. Highway underpasses designed for wildlife crossings have helped reduce road mortalities, though collisions remain a significant problem.

Human-Wildlife Conflicts

Direct encounters between panthers and people are relatively rare, and attacks on humans are even rarer. Still, it is crucial for those living in panther country to take precautions, such as keeping pets indoors and securing garbage to avoid attracting prey animals. Experts advise that if you encounter a panther in the wild, you should make yourself appear large, speak firmly, and slowly back away. Running may trigger a chase response.

Unfortunately, vehicular collisions rank among the leading causes of death for Florida panthers. Many succumb while attempting to cross major highways like Interstate 75 (Alligator Alley). In response, wildlife managers have installed underpasses and fences in key areas, significantly cutting down on collisions. However, as development intensifies, road mortality remains a challenge that requires ongoing infrastructure planning.

Debunking Myths About Black Panthers in Florida

Popular culture often features black panthers, and many Floridians claim to have seen large, black cats in local woodlands. These stories likely stem from the global fascination with melanistic leopards or jaguars—true “black panthers” found primarily in Africa, Asia, and parts of Latin America. The mystique surrounding big cats easily embeds itself in local folklore.

Despite persistent rumors, there has never been a confirmed case of a melanistic cougar in Florida. Jaguar or leopard populations do not exist in the state, according to wildlife experts. Many supposed "black panther" sightings are eventually attributed to black dogs, bobcats with darker coats, or even large housecats viewed from a distance.

To ensure the Florida panther’s continued survival, wildlife managers, policymakers, and citizens must work hand in hand. Supporting conservation groups, pushing for habitat-friendly development, and educating ourselves about safe coexistence can make all the difference. By safeguarding these majestic cats, we also protect the broader ecosystems they help stabilize—and preserve a vital piece of Florida’s wild heritage for generations to come.