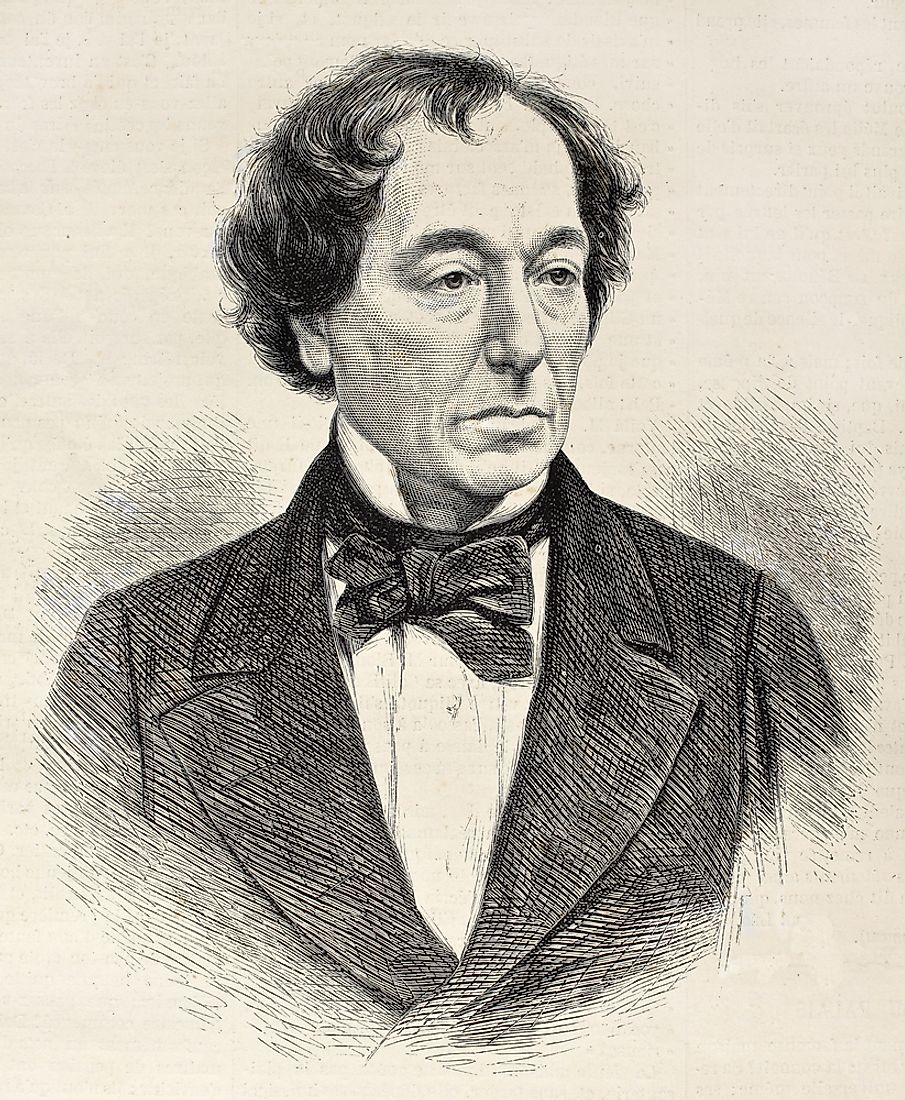

Benjamin Disraeli - Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom

5. Early Life

Benjamin Disraeli was born on December 21st, 1804, in Bedford Row, Bloomsbury, London, to a family of Jewish and Italian origins. His father would later on renounce Judaism, and had all four of his children baptized. Disraeli went to a dame school in Islingston from the ages of 6 to 8, and then attended Reverend John Potticary's St. Piran's school at Blackheath. He then attended the school ran by scholar Eliezer Cogan in Walthamstow, and graduated from there when he was 17. Upon graduation, he was apprenticed to a firm of solicitors in London, but he found the position incompatible with his sensational nature. He quit his position, and in the following several years travelled extensively and published several novels.

4. Rise to Power

By 1831 Disraeli, then an active member in England's literary circle, decided to enter politics. He joined the Tory Party and, after several failed attempts, finally won a seat in the House of Commons in 1837. In the following decades the House of Commons was split, and the Whig and the Conservative parties took turns to govern. It also saw the control of many minority governments. In 1865, when the Whig-Liberal led government fell, Lord Derby, known as "The Earl of Derby", formed yet another minority government, and appointed Disraeli to act as Chancellor of the Exchequer. Then, in 1868, when Derby decided to retire, Disraeli became Prime Minister. When his party lost the election that year, however, Disraeli resigned. It was not until 1874, when the Conservatives won another big victory, that Disraeli became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

3. Contributions

During his tenure, Disraeli past several important reforms. Domestically, the Artizans' and Labourers' Dwellings Improvement Act helped to clear much of Britain's slums effectively, and the Public Health Act of 1875 further codified laws regarding the regulation of slums. He also passed a series of factory acts throughout the years, intending to prevent the exploitation of labor, and of legitimate unions as legal representatives of workers. Then, in the sphere of international relations, Disraeli made bold moves and expanded the Great Britain's imperial prestige. He successfully bought shares of the Suez Canal, conferred Queen Victoria as the Empress of India, and defended the British Empire's interests against Russia in the Congress of Berlin.

2. Challenges

Through most of Disraeli's political career, the Conservative party was split over key issues, and they often lost popular support because of the dissent. After Disraeli became the leader of the party in 1872, he radically reformed the party, and made its stance into one clearly distinguishable from that of the Whig-Liberal Party. He defended the monarchy and the House of Lords, as well as the Church of England. He also insisted on radical measures to consolidate the Empire against rebels and foreign threats. All of these values were later on reflected in his policies. During his ministry, Russia was a big threat to Great Britain, and when the Turks yielded to the Russians after a major conflict, it was agreed that Russia would take considerable territories in Europe that had belonged to the Ottoman Empire before. Disraeli firmly protested such measures, and forced Russia to attend the Congress of Berlin, during which he successfully prevented Russia's further expansion throughout Europe.

1. Death and Legacy

Disraeli died on April 19th, 1881, in London at the age of 76. He had long suffered from gout, asthma and bronchitis. Disraeli was instrumental in forming the Conservative Party as a unified and coherent party, and in doing so also consolidated the two-party system that is iconic of democracy in the U.K. still today. The reforms he carried out regarding working conditions and unions won him the support of the working class people, and established their voting preferences for favoring the Conservative Party. He was also a firm believer in the British Empire and the British Monarchy, and his measures consolidated Britain's imperial power at his time, but such measures also produced colonial domination and oppression, which led to resistance movements against the British around the world in the following century.