How Caribbean Islands Played A Part In The European Conquest On North America

- Luxury goods imported from the Caribbean colonies contributed the development of a consumer society in North America and the rise of a colonial elite.

- The Caribbean islands received a majority of the slaves shipped from Africa, and exported many of them to North America.

- Piracy flourished in the Caribbean and expanded into North America, threatening trade routes and enriching local officials.

Stories of the European conquest and settlement of North America tend to focus on the northern colonies and the European powers back home. But the European colonies in the Caribbean islands had a significant part to play in the development of North America. The settlement of the Caribbean islands in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries provided bases of operation for further expansion. They also proved to be a significant economic boon. The Spanish brought home ships laden with gold, and while the other countries largely failed in their search for similar treasures, they established cash crops, such as sugar and tobacco, which provided significant boosts to their economies, and in part supported expansion in North America. The Caribbean islands also exported slaves to North America, who had a driving role in the economy. Pirates were another Caribbean export, and they were both a threat to trade and an economic boon, particularly for local officials.

Background: Colonizing The Caribbean

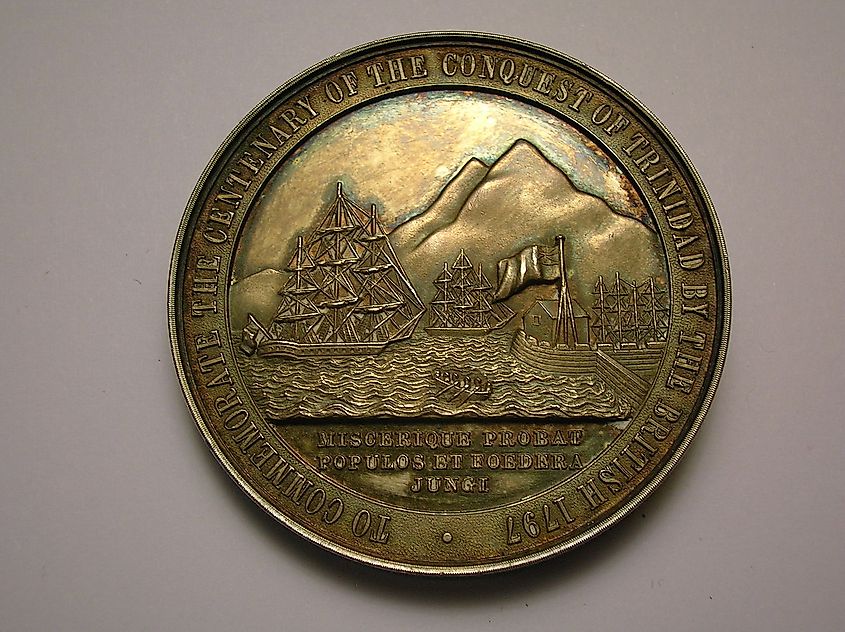

Spain first established settlements in the Caribbean in 1493, following Christopher Columbus’ initial voyage. Their presence nearly wiped out the native population. Seeking their own share of the apparent wealth the Spanish found in the Caribbean islands, other European powers moved to establish their own settlements in the region in the seventeenth century. Early British settlements include Bermuda (1612), Saint Kitts (1623), and Barbados (1627). Early French colonies include Saint Kitts, which France split with Britain in 1625, Guadeloupe (1635), and Martinique (1635). These settlements served as bases for further conquests. In 1655 Britain seized Jamaica from Spain, and the island soon became a leading exporter of sugar. The Dutch followed suit, establishing the Dutch West Indies in the 17th century, and from 1672 Denmark-Norway established its presence in what is now the Virgin Islands. While these European powers hoped to follow Spain’s example and find gold in plenty, but their hopes were not fulfilled and they turned to agriculture instead.

Cash Crops

The European Powers were almost constantly at war with one another, and the territories frequently changed hands in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. As they fought for dominance in the Caribbean, their economies became increasingly dependent on the rich exports from the region, which helped finance further expansion and solidify British dominance in North America.

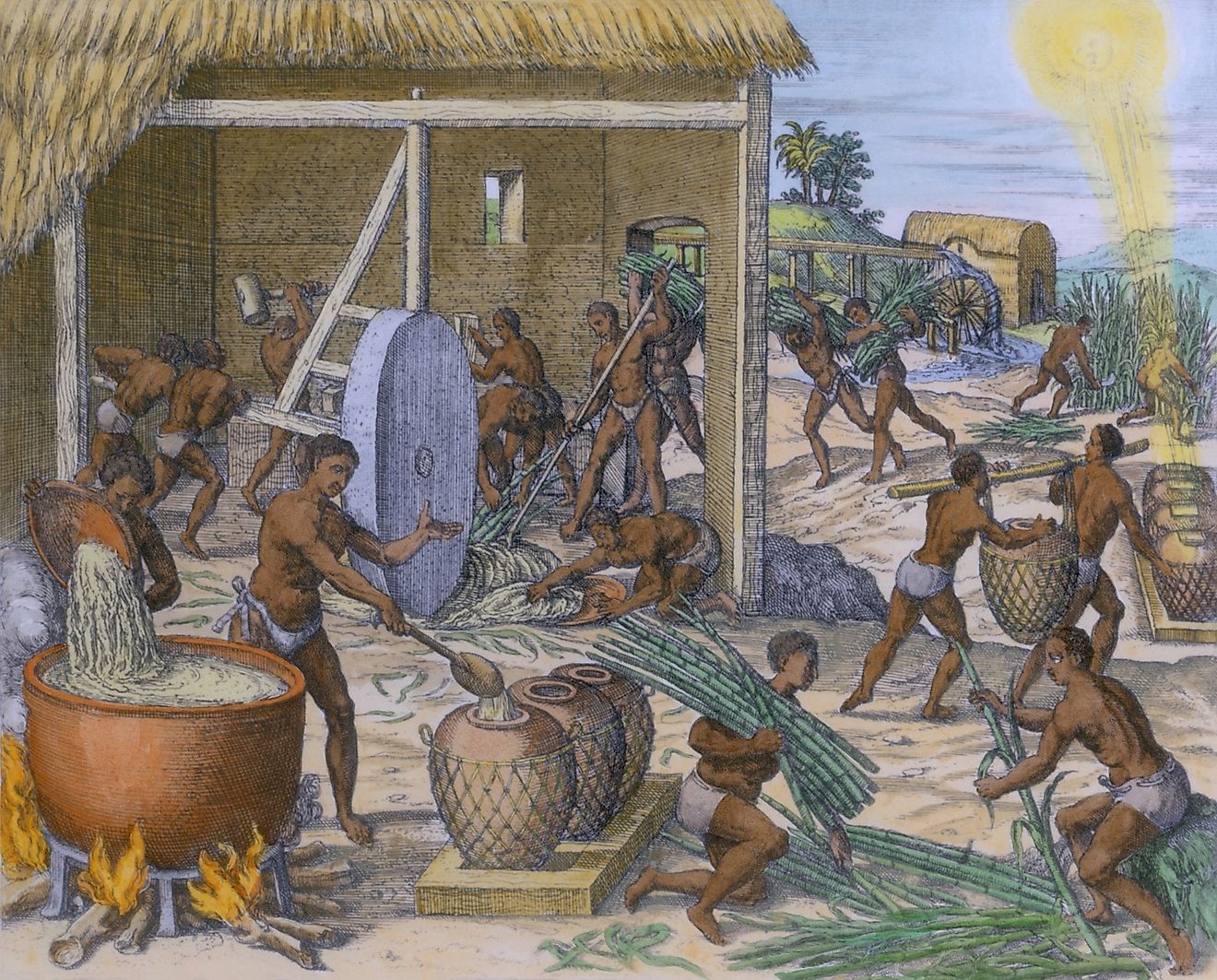

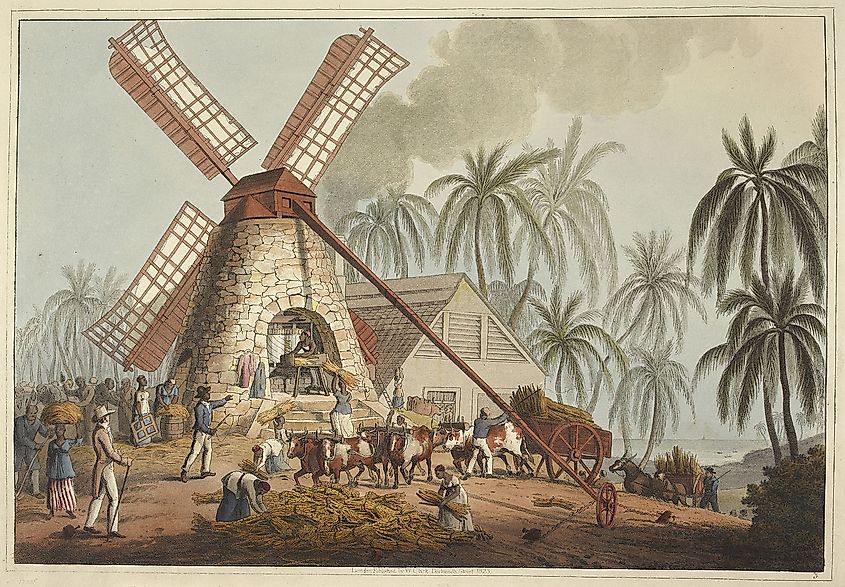

Caribbean colonists established plantations to grow luxury products, which would be shipped back to Europe and sold for a pretty profit. Sugar quickly became the most valuable Caribbean export. While tobacco and sugar were the primary cash crops, others included rice, coffee, and indigo. And its North American colonies particularly benefited from these cash crops. While Spain and France dominated sugar production in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the balance of power shifted in the eighteenth as the French colony of Saint-Domingue and British colony of Jamaica emerged as the biggest sugar producers.

Increasingly in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries direct trade developed between the Caribbean and the growing North American colonies as the North American colonists grew wealthier and began purchasing luxury goods. Imports from the Caribbean contributed to the development of a “consumer society” and the rise of colonial elites, which in turn fueled the growth of cities in North America.

As new settlers carried little money with them when they arrived in North America, and the colonies lacked the authority to mint new coins, the colonists turned to a system of barter and exchange. In Virginia the rate of exchange for tobacco was standardized, and it became a form of currency in the colony. Since the Caribbean colonies dedicated most of their agriculture to cash crops, they were reliant on outside sources for their sustenance. The two regions became interdependent on one another. The Caribbean colonists exchanged their cash crops for food, livestock, and raw goods, particularly timber, from the North American colonies. Mahogany was a popular export from the Caribbean from the colonial elites among the North American colonists, as the wood was rare and used to fashion their homes with fine furniture.

Slave Trade

The Caribbean plantations relied on slave labor to produce their high yields and profits. While the institution of slavery is often tied to America in the popular imagination, the majority of slaves were sent to the Caribbean (as well as Brazil) to work on the plantations there. The trans-Atlantic slave trade made up a portion of the “triangular trade” system between Europe, Africa, Brazil and the Caribbean, and North America. In practice ships carrying slaves from Africa to the Caribbean would then carry on to North America transporting luxury goods. In practice, the slave ships were not suited to the second leg of the trip, and upon delivering the slaves in the Caribbean, they would turn around and return to Africa to pick up more slaves. As a result, slaves became another export from the Caribbean to North America.

Fewer than 4% of the more than twelve million Africans enslaved in the trans-Atlantic slave trade were sent directly to North America in the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. Those that were imported from the Caribbean represented a significant contribution to the slave population in North America. Just as slave labor drove the economic success of Caribbean plantations, it drove economic growth and expansion in North America, and the rise of capitalism.

Piracy

Rich trade in the Caribbean provided the perfect opportunity for piracy to flourish in the region from the sixteenth century to the early nineteenth century. Islands such as New Providence, with their naturally sheltered harbors and natural resources developed as pirate havens, and the town of Nassau, in particular, became a base for pirate activities. Piracy also expanded into North America. After years of operation in the Caribbean, the infamous pirate Blackbeard established a base on Ocracoke Island, North Carolina, in 1718, and made an agreement to share his booty with the North Carolina governor Charles Eden.

Pirates operating out of the Caribbean, and those like Blackbeard who moved north, were a genuine threat to trade. But some also enhanced the economy of the North American colonies by trading their stolen goods and slaves, often to the benefit of particular individuals such as the governor of North Carolina.

From the export of luxury goods and slaves to piracy, the Caribbean islands were tied to the expansion and economic development of North America.