Major Infectious Threats In The 21st Century

- Four variants of Ebola virus have been identified so far

- Swine flu killed between 151,700 to 575,400 people between 2009 to 2010

- By January 2020, Yemen had reported 2.2 million cases of cholera

Health across the globe had improved significantly over that past century. The world’s population has better access to clean water, sanitation, and medicine compared to the past. Conditions that killed and crippled people decades ago now have vaccines or can be cured. The modern world, however, continues to confront a significant threat to human health, as demonstrated by the recent outbreaks. The world is also becoming more interconnected due to improved international travel via air, road, sea, and rail, which has raised the risk of international outbreaks. Even without global spread, disease outbreaks are very costly. In recent years, the world has faced Ebola, H5N1, H7N9, Avian flu, and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), among others.

Ebola

There are four strains of Ebola viruses in West and Equatorial Africa. Fruit bats are the main vectors of the virus. The virus spreads from fruit bats to other animals through direct or indirect contact. Large scale epidemics in primates or mammals such as forest antelopes can occur. Primary transmission to humans can occur either through handling sick and dead infected animals in the forest or through direct contact with infected bats. Secondary pathogen transmission occurs through human-to-human contact with infected body fluids and corpses. The largest Ebola outbreak in the 21st century began in March 2014 and spread to most parts of West Africa. By November 14, 2014, there were 21,296 cases of the Ebola reported by the WHO, and case fatality rates were between 21.2% and 60.8%. The surge was mainly fuelled by poor sanitation, lack of appropriate health services, and poor and unsafe practices of burying the dead. Traditions in parts of West African countries involve washing and touching dead bodies before they are buried and puts families and community members at risk.

H1N1 Swine flu

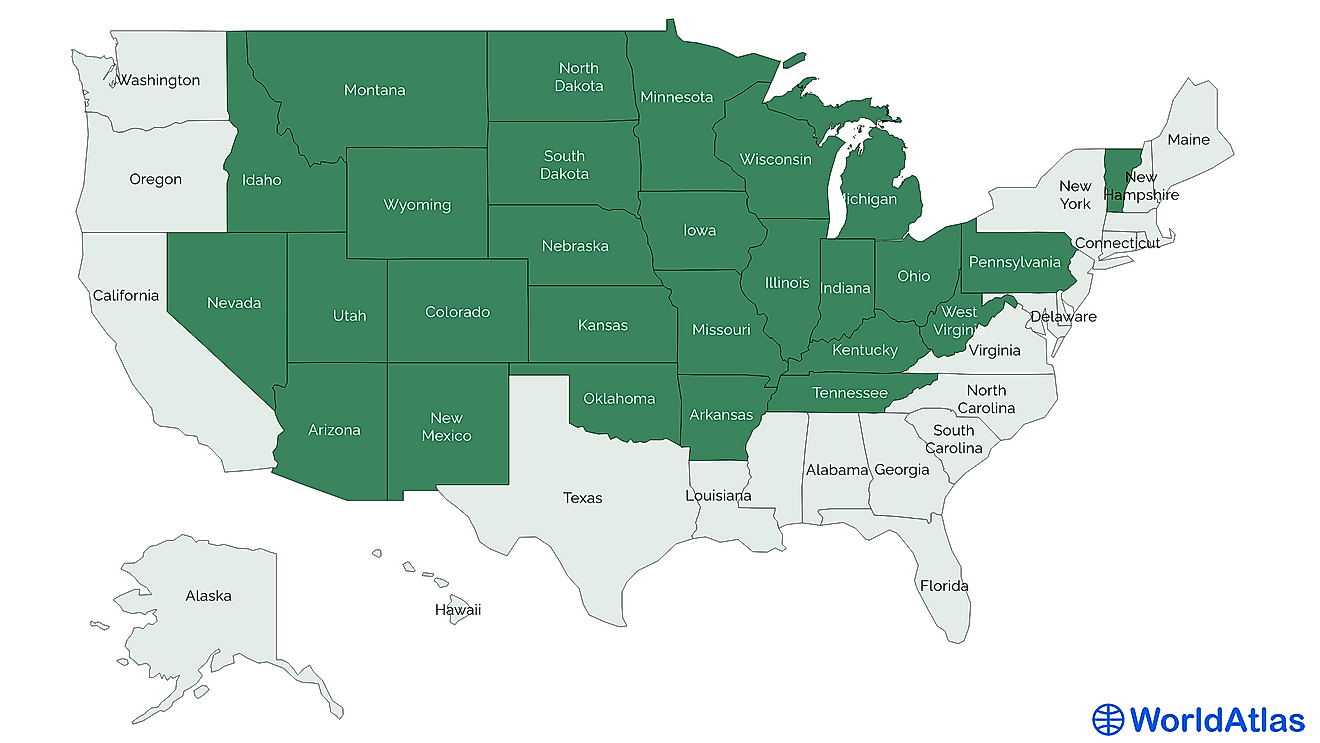

The H1N1 influenza virus, which is also known as the swine flu, led to a global outbreak that lasted from 2009 to 2010. According to a study by the CDC, the outbreak resulted in deaths of between 151,700 to 575,400 people. The virus was identified for the first time in the US in April 2009. The virus had a remarkable combination of influenza genes and had never been identified in humans or animals. The genes of the virus were closely related to the European H1N1 virus and the North American H1N1 swine influenza virus.

The Outbreak of Cholera in Haiti

Cholera diseases refer to acute diarrhea infection. It can be acquired through the consumption of contaminated water and food. The bacteria causing cholera is known as Vibrio cholera. Haiti experienced a cholera outbreak in October 2010, and this was only ten months after a massive earthquake claimed the lives of more than 200,000 and displacing more than 1 million people. It was the first of its kind in the country in more than a century. The first case of the disease was experienced on October 12, 2010, in the rural parts of Central Plateau in Haiti. The majority of the victims died in their homes without medical attention. Initially, public health authorities had not identified the disease, but acute watery diarrhea was observed. The outbreak, which infected thousands of people across the country, was later identified as cholera. Some of the reasons cited for the rapid spread include favorable conditions for the proliferation of the disease, the absence of cholera immunity among the local population, and deficiencies in sanitation, water, and health facilities. The origin of the disease was controversial, with initial cases being reported near the Nepalese United Nations Peacekeeping campsite.

The UN confirmed the link by admission in 2016. The UN’s office acknowledged that they could have played a role in the initial outbreak of cholera. The acknowledgment, however, stopped short of admitting that the UN was the primary cause of the epidemic. Throughout the nine-year cholera outbreak, nearly 10,000 people died. January 2020 marked the first time the country had gone an entire year free from new cases since the outbreak of the deadly waterborne disease.

Cholera Outbreak in Yemen

Another outbreak of cholera was experienced in Yemen in October 2016, and a much larger wave followed it in 2017. The outbreak is listed as the largest in epidemiologically recorded history. As of January 2020, the country had reported 2,260,495 cases of suspected cholera and 3,767 loss of lives. The cause of the epidemic in the country is still unclear. The country has, in the past, faced several cholera outbreaks, but none was comparable to the case the country experienced in 2020. The incidence of cholera during the rainy periods can be high due to the contamination of water supplies. During the dry season, cholera incidence is also high since people are more dependent on unsafe drinking water. The epidemic has been made worse by the civil war in the country that has led to the mass movement of the population, shortage of water supplies, intensified sanitation problems, and the disruption of health services. It is estimated that nearly two-thirds of the population in the country do not have access to proper sanitation and safe drinking water supplies.

Zika

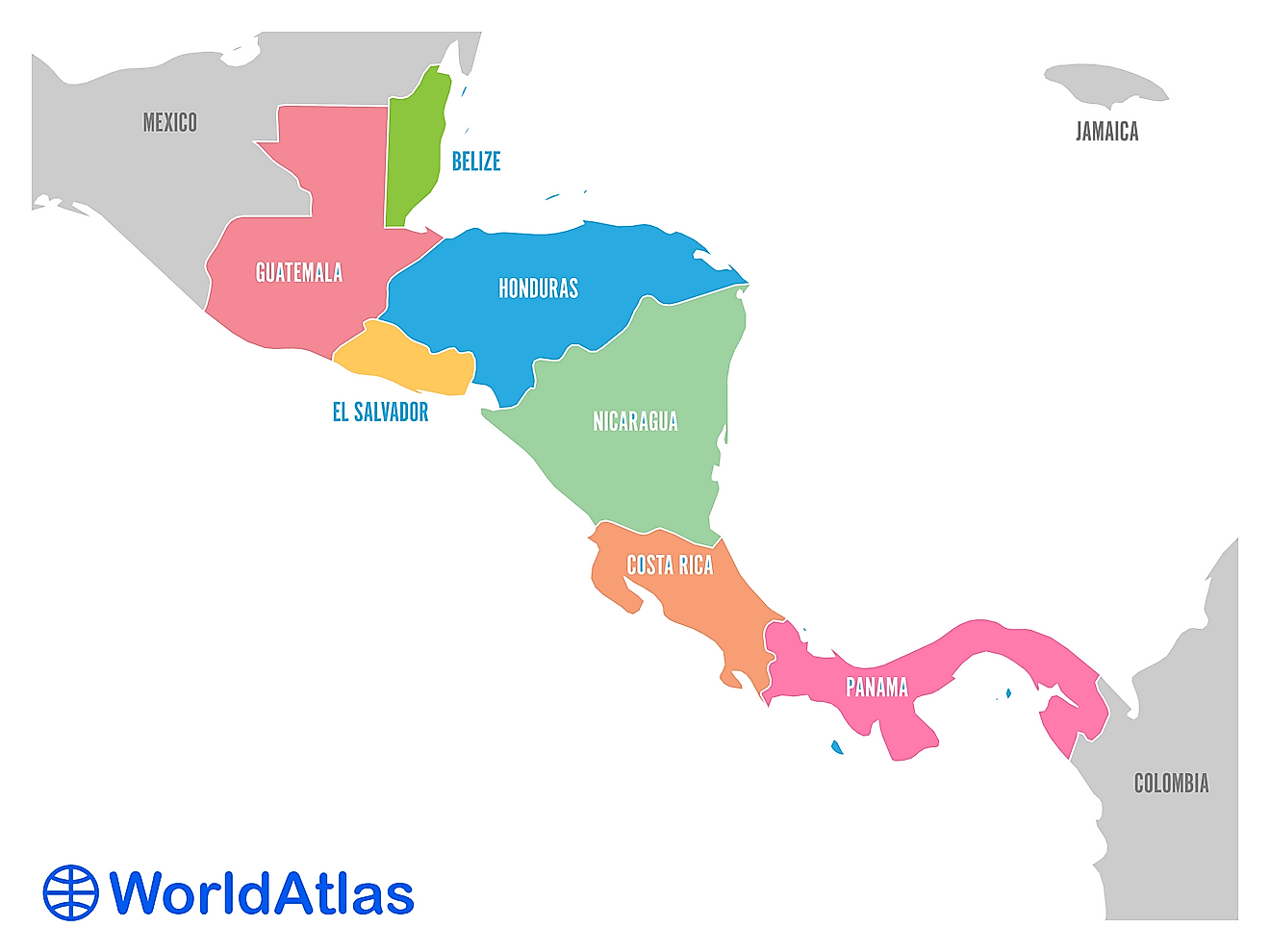

Zika is spread by infected Aedes mosquitos or through sexual contact. Most people infected with the virus either do not show any symptoms. They could also exhibit some mild symptoms. Among the expectant women, the virus could be transmitted to the fetus causing severe defects at birth. Currently, there is no vaccine or medicine to treat Zika. The disease first emerged in Brazil in 2015. The virus subsequently spread throughout most of Latin America, the Caribbean, and the US. In February 2016, the WHO affirmed that Zika was a public health emergency of international concern. In the US, over 43,000 people had tested positive for Zika by early 2019. Some of the measures that have been taken to contain the virus include vector/mosquito control, provision of contraceptives, and launching campaigns to help empower pregnant women, their families, and communities to take action to stop spreading the virus.

SARS

This virus is airborne, and it is spread by the infected person when they sneeze or cough. The viruses are in the saliva droplets, and anyone within a close range can inhale air with the viruses. It can also be spread through human to human contact or touching infected surfaces. The first human infection occurred in 2002 in Guangdong province, China. It is believed that a strain of the coronavirus in small mammals mutated and infected humans. The virus later spread, affecting 26 countries in Asia, South America, North America, and Europe. The SARS pandemic was finally controlled in July 2003 after the effective implementation of measures such as isolating suspected carriers and thorough screening of travelers from affected nations. In the course of the epidemic, there were 8,098 reported cases of infection and 774 deaths. People aged 65 and above were particularly at high risk with the age group accounting for over half the deaths reported. In 2004, a smaller SARS outbreak was reported. The second outbreak was associated with a medical laboratory in China. It is believed that it began when someone came into contact with the lab sample of the virus.

MERS-CoV

The Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was identified for the first time in 2012 in Saudi Arabia. The virus was isolated from a patient who had an acute kidney injury and acute respiratory distress. The patient subsequently died. The disease has a mortality rate of over 35%. Since 2012, there have been over 2500 confirmed cases of the disease resulting in 862 deaths. The reported cases have been identified across 27 countries. Over 80% of the cases have been reported mainly in Saudi Arabia. Transmission of the disease requires close contact between humans. MERS-CoV has so far not reached epidemic potential. Growing evidence has implicated the dromedary camel as the primary animal host in the spread of the virus.

H5N1 Bird Flu

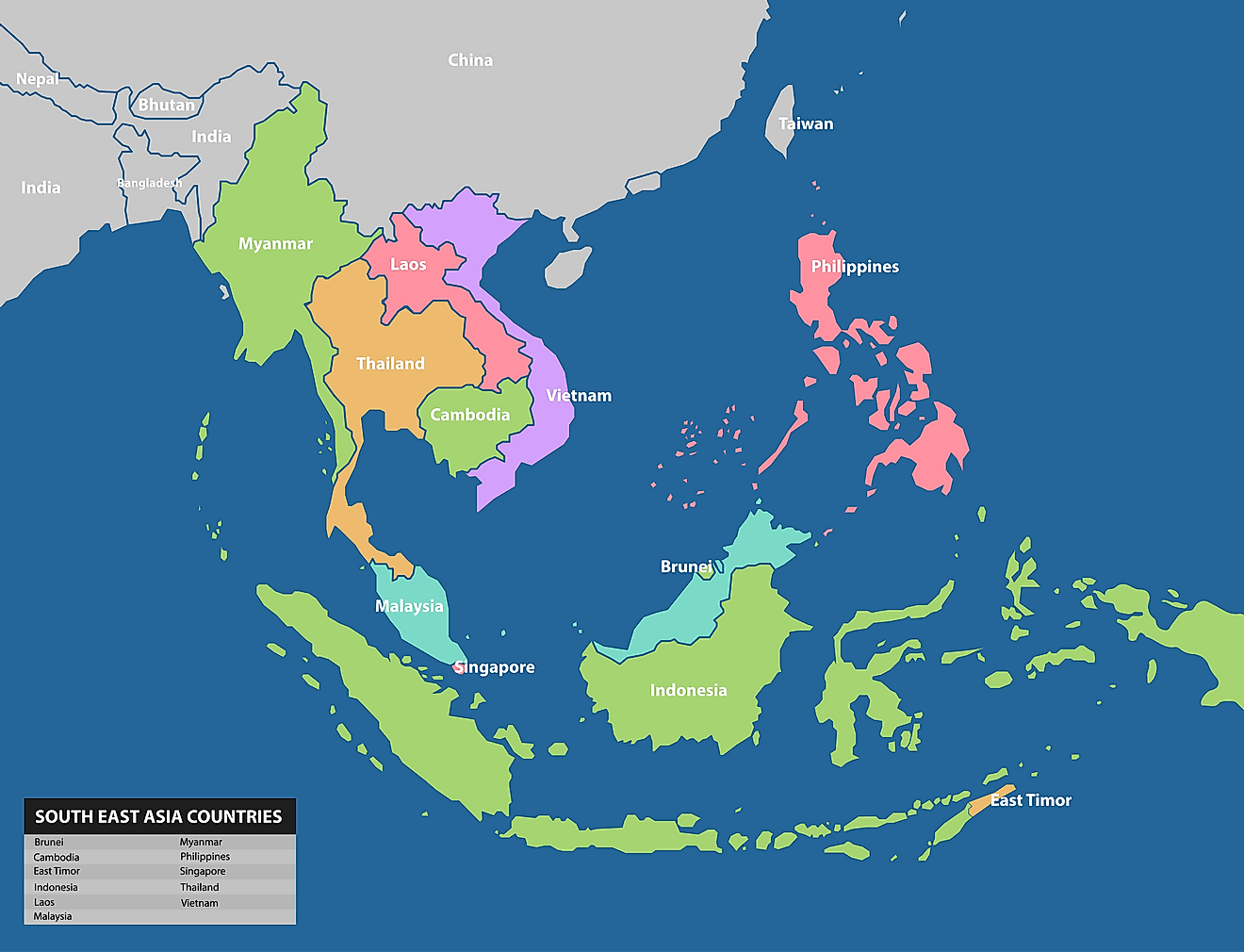

Avian Influenza (H5N1) is widely referred to as “bird flu.” It is caused by one of the strains of Influenza virus H5N1. Different variants of avian influenza affect wild and domesticated bird populations across the world. They are a highly pathogenic group of viruses that spreads so fast among flocks leading to high mortality rates in birds. Cases of infecting humans were first reported in 1997 following its outbreak in Hong Kong that led to the death of six people. The disease resurfaced in February 2003 in Hong Kong, with two cases of infection that resulted in one death. The December 2003 to February 2004 outbreak began when South Korea identified the virus in the poultry population. The disease was later identified in nine Asian countries, including China, Japan, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Indonesia, South Korea, and Pakistan. Twenty-three other confirmed cases of human infection were reported resulting in 18 deaths in Thailand and Vietnam. Since 2003, bird flu has been responsible for 455 deaths worldwide. Indonesia has suffered the most deaths at 168, with most mortality occurring between 2003 and 2009. Egypt has had the second-highest number of deaths related to the virus at 120. Most deaths in Egypt occurred in the periods of 2010 to 2014 and 2015 to 2019, with 50 and 43 deaths, respectively.

H7N9

Human infections of H7N9 avian influenza was first reported in March 2013 in China. Sporadic human infections with the viruses in China have been reported ever since. As of December 2017, the total number of human infections reported was 1,565, with a mortality rate of 39%.

Plague

Madagascar accounts for 75% of all cases plague cases reported worldwide with an annual incidence of between 200 and 700 suspected cases. Most cases are of the bubonic plague. In 2017 the country experienced an unusually large outbreak of the plague with 2,414 suspected clinical cases (78% of which were pneumonic plague).

Tackling Infectious Threats

Global health security depends on high levels of awareness and collaboration between countries, organizations, agencies, and communities. Collaboration is particularly important because it can help improve early detection and control. Recent outbreaks have demonstrated that infectious threats can be challenging even with sound public health surveillance systems. To avoid international outbreaks, isolation of infected people for specialized treatment, screening of passengers, and travel restriction to affected areas should be considered.