Maria Sibylla Merian: Famous Scientists in History

5. Early Life

The life of one of the world’s first female entomologists began on the 2nd of April, 1647, in Frankfurt, Germany. Maria Sibylla Merian was the daughter of Matthaus Merian the Elder, a Swiss engraver and owner of one of Europe’s largest publishing houses in the 17th Century. He died when she was three years old. Shortly after her father’s death, Maria’s mother remarried. Her stepfather, Jacob Miller, was a still-life painter, and encouraged Maria in painting flowers. He taught her to draw, mix paints, to paint in watercolors, and to make prints. Interested in the silkworm breeding trade that was introduced in Frankfurt at the time, Maria had observed the metamorphosis of a caterpillar by the time she was thirteen years old, which was a discovery that predates any other publicized accounts by nearly ten years.

4. Career

At the age of eighteen, Maria married one of her stepfather’s pupils, Johann Andres Graff. They moved to Nuremberg two years later in 1667, where Maria taught the daughters of wealthy families in the arts of embroidery and painting. This connection provided her with access to some of the area’s finest gardens. While in Nuremberg, she continued her research and drawings in entomology, had two daughters of her own, and published her first book: a three-volume edition titled New Book of Flowers. Her second book, Caterpillar, Their Wondrous Transformation and Peculiar Nourishment from Flowers, was published in 1679. After twenty years of marriage, Maria divorced her husband in 1685 because of his “shameful vices”, and moved her two daughters and elderly mother to a Labadist religious commune north of Amsterdam.

3. Discoveries

While at the religious commune, Maria continued to pursue her research, focusing specifically on insect specimens that were brought back from a Labadist religious community in Suriname in South America. With the financial collapse of the religious colony in 1691, she moved to Amsterdam where she and her daughters set up a studio. Her distinction and fame allowed her access to many collections of insects while in Amsterdam. Maria documented moths and butterflies in various stages of metamorphosis, describing in great detail the colors, forms, and timing of each stage. Through her studies, research, and paintings, and by taking a more ecological approach to the study, Maria was able to demonstrate that caterpillars indeed went through a metamorphosis, and did not reproduce via spontaneous generation from decaying matter, as was the common thought of the day.

2. Challenges

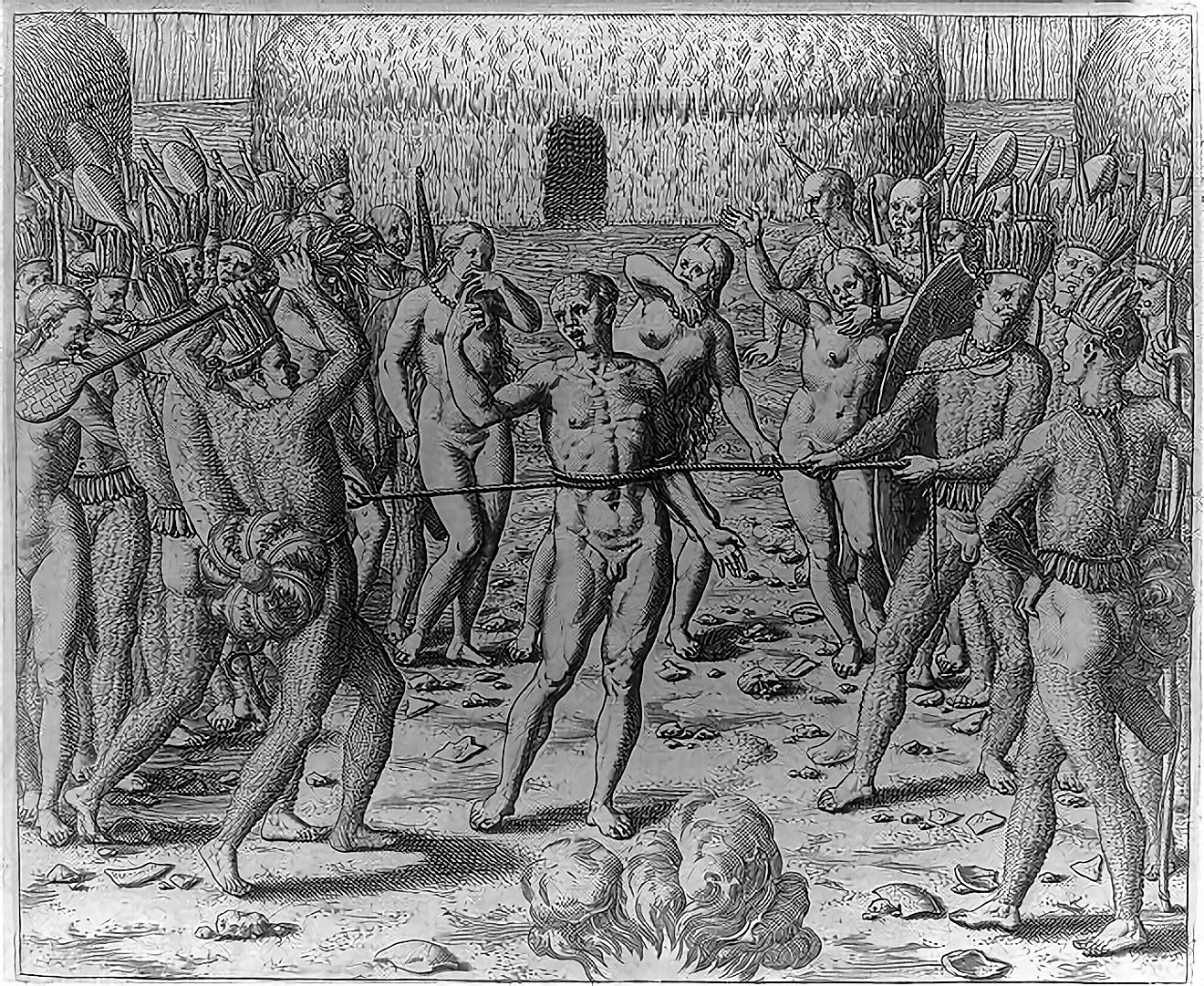

Growing tired of the limited specimens available to her in Amsterdam, Maria sold everything she had in 1699 and, with her youngest daughter in tow, set sail for the Dutch colony of Suriname in South America. The weather was hot and humid, and although the jungles were teeming with live specimens for her to study, it was a dangerous place to be. However, with her keen observation skills, Maria discovered much about the insects, climate, plants, and animals of the area. She also observed the Dutch treatment of slaves, which provided the world with an in-depth historical account of daily life in Suriname at the time. Two years into her research there, Maria became sick with malaria and that, coupled with the hot climate, caused her to return to Amsterdam. Once back there, she published her influential work on her findings as Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium.

1. Death and Legacy

Maria was partially paralyzed from a stroke in 1715, and died in Amsterdam in 1717. Her daughters helped publish her third volume of the metamorphosis series. During her stellar career, Maria painstakingly described the life cycle of over 186 insect species. She revolutionized the field of entomology with her detailed and beautiful illustrations, and helped to put the field of entomology on a more established foundation. Because her works were published in German and not Latin, this allowed larger numbers of ordinary people to more easily access her research. Her books were so popular that there were 19 editions published between 1665 and 1771. The Russian Tsar Peter I, who admired Maria, hung a portrait of her in his study, while Johann Wolfgang von Goethe marveled at her ability to simultaneously depict both science and art in her paintings. Her picture once adorned the 500 Deutschmark note, as well as finding its way onto many German stamps. Many schools have been named after Maria, as well as a modern research vessel that was launched in Germany. Additionally, six plants, two beetles, and nine butterflies have been named in her honor.