The Troubles Of Northern Ireland

For three decades, Northern Ireland was beset by a dark era of violence and conflicting nationalistic ideologies. The conflict era is now referred to as ‘the Troubles’, which led to the division of the country along sectarian lines and the perpetration of violence.

Historical Background

The problems of Northern Ireland, which became worse than ever following 1968, had been brewing for many prior years. The unionists, who were mostly Protestant, had been the dominant force in parliament and supported to remain in the UK. Nationalists and republicans on the other hand, mainly Catholics, wanted a unification with southern Ireland to form the Republic of Ireland. Northern Ireland was created in the 1920’s, and the Unionists embarked on efforts to cement their political and social dominance in the region. Before the troubles, tensions between the two factions had been rife across Northern Ireland. The tensions were primarily territorial, although they took a religious dimension. Nationalists and Republicans had been subjected to discrimination and oppression under the Unionists, and this fostered their dissatisfaction.

Escalation of Tensions in the 1960s and 1970s

The violence started in Londonderry on October 5th, 1968, when Nationalists took to the streets to demand an end to decades-long practices of discrimination and oppression. Riots broke out which quickly turned bloody after they were intercepted by Loyalists. A series of violence and conflicts rocked Northern Ireland, despite interventions by successive UK governments. In 1969, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) was formed from the Official (IRA). PIRA aggressively pursued the quest for unification of Ireland and subsequent withdrawal of UK from the region. PIRA was determined to use violence to achieve its objectives, especially when talks with the UK proved unsuccessful.

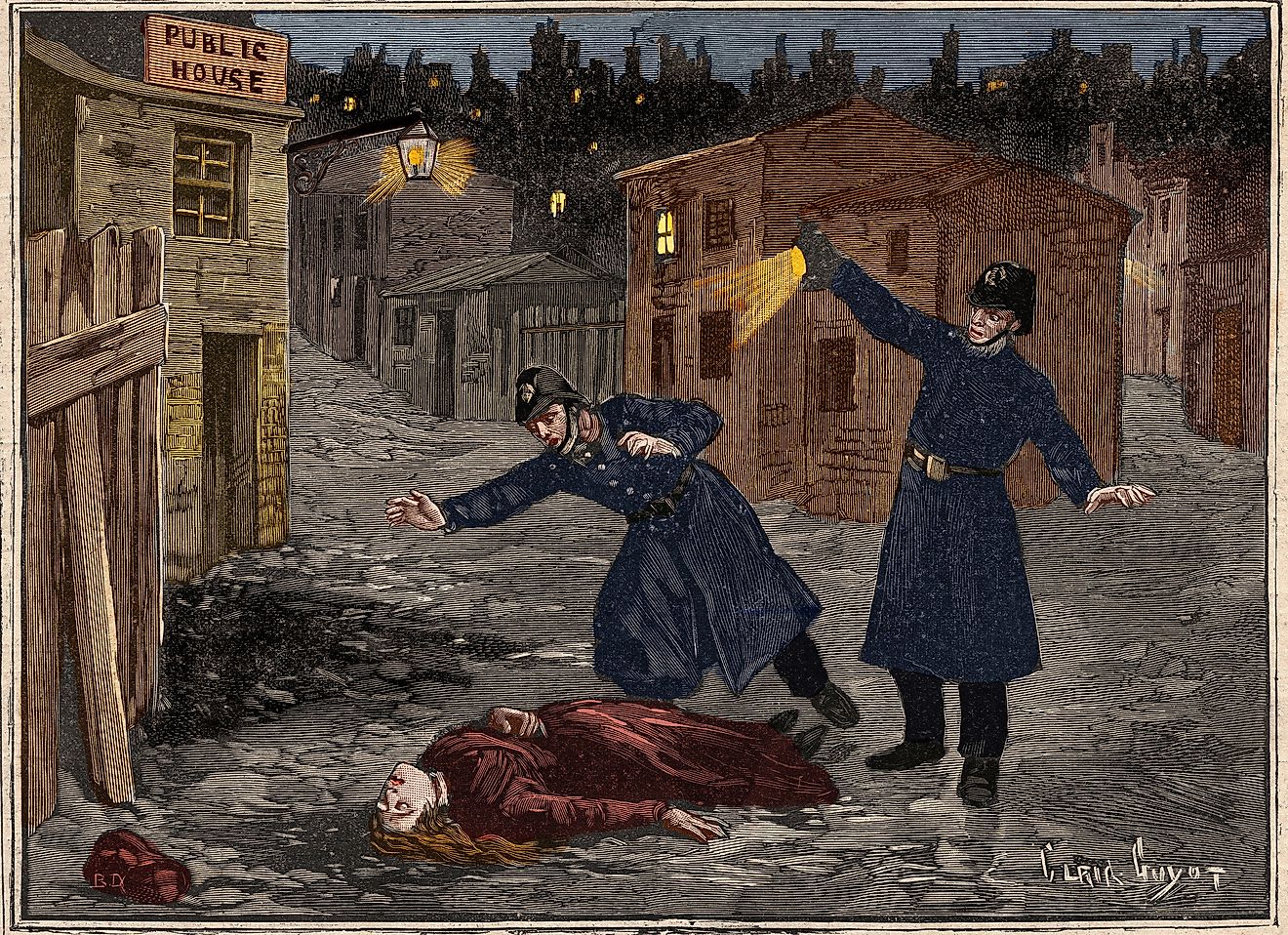

The major warring factions were PIRA and Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) against the British Forces and loyalist paramilitary groups, the latter including the Ulster Volunteer Force and Ulster Defense Association. Unionists’ and Nationalists’ followers also waged war against each other, through terrorist acts such as bombing, shooting, rioting and burning of houses. Violence between warring factions surged especially in 1972, when British forces opened fire on marching protesters on a day that has been referred to as the ‘Bloody Sunday’.

Casualties and Divisions

The decades-long war caused the deaths of over 3,500 people, most of whom were civilians, and around one thousand others were physically maimed. During the conflict, Northern Ireland was segregated along loyalist and nationalists lines. Neighborhoods were divided, mainly by use of barbed wire and walls to mark territories. Loyalists’ and nationalists’ armed forces protected their individual communities. Freedom of movement for the citizens of Northern Ireland was heavily curtailed.

The Road to Peace

As the wars raged on, the British attempted to bring peace in Northern Ireland by suspending Parliament and the existing Unionist-controlled government. The UK’s goal was to facilitate the establishment of a unitary government that represented both Unionists’ and Nationalists’ interests. Peace agreements began with the Sunningdale Agreement, signed in 1973. A new administration took over Northern Ireland in 1974, where Catholics and Protestant shared executive powers. The government was however weakened by resistance, from Protestants who were opposed to sharing power. These anti-power sharing loyalists would later spark new conflicts through a workers’ strike and necessitate direct rule from the UK.

The UK would attempt to end the conflicts through various peace initiatives, but none proved successful. Support for the Irish Republican Army (IRA) surged during hunger strikes by republican prisoners pioneered by Bobby Sands in 1981. The strikes fueled protests by the Nationalists which led to wars continuing through the 1980’s. The IRA continued with its aggressive quests for British withdrawal, restructuring into small armed groups, which were harder to penetrate. The IRA orchestrated an assassination attempt on Margaret Thatcher in Brighton in 1984. The faction imported arms from Libya and carried out terrorist attacks such as bombings and shootings.

A New Dawn

Several ceasefires and talks between the warring factions led to the Good Friday (Belfast) Agreement in 1998. The agreement reinstated self rule in Northern Ireland. The agreement stipulated that the constitutional status of Northern Ireland would be determined by Northern Ireland’s people who would acquire both Irish and British citizenship. The unification of Northern Ireland with the south would be decided through referendums in both regions at the same time. Power in the new government would be evenly distributed between Unionists and Nationalists. The people of Northern Ireland voted to pass the referendum, and a coalition government was established. Several conflicts after the agreement weakened the unitary government. Between 2002 and 2007, direct rule by the UK was reinstated.

A Peaceful Era

A coalition government was formed in 2007 between Martin Guinness of the Sinn Fein Party, which was a political section in the IRA, and Reverend Ian Paisley, leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). The government was viewed as a significant stride to ensuring peace in a region that had been divided by decade’s long wars. Tensions in Northern Ireland are, however, not vanished. Catholics and Protestants continue to be subtly divided, although there has not been a violent manifestation of existing rife.