Great Pacific Garbage Patch

- The patch covers a territory the size of three Frances, or 1.6 million square kilometers.

- The actual count of individual plastics in the patch may be up to 3.6 trillion, twice the amount estimated.

- The Patch is also known as the "Pacific Trash Vortex."

There are five rotating ocean currents of varying sizes in the world, known as gyres. Two are located in the Atlantic Ocean, two in the Pacific, and one in the Indian Ocean. This article concerns the North Pacific Gyre, situated between the US states of Hawaii and California, around 32 °N and 145 °W, although it moves any which way depending on the time of the year.

It is the site of the largest of the five plastic accumulation zones in the world’s oceans, consisting of at least 80,000 tonnes of plastic debris that floats freely, a number far greater than estimated before studying the Great Pacific Garbage Patch closely.

Contents:

- Mass, Count And Concentration

- Surveying The Patch

- How Did It Form And What Is It Made Of?

- Impact On Ocean Life

- Effects On Society

- What Is Being Done And Future Prospects

Mass, Count And Concentration

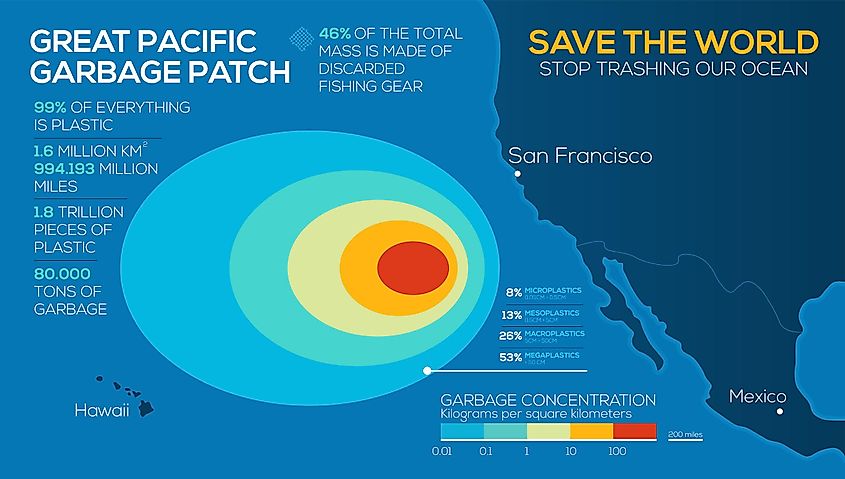

While the debris on the outer edges of the patch is more sparse, composing an estimated 20,000 tonnes of plastic, there are at least 80,000 tonnes of plastic debris in the epicenter and its close surrounding. The plastic pieces count is also estimated to be about 1.8 trillion, which is 250 pieces for every human on the Earth. Even at that, surveyors admit that this estimate is modest and that the actual count of individual plastics may be sitting at twice that amount, at 3.6 trillion.

The center of the patch has the highest concentration of pollution, with hundreds of kilograms of debris per km2 in the epicenter, and up to 10 kg per km2 towards the edges of the patch. The waste itself is at all levels of the ocean, including the ocean floor. Since the patch is located exactly between two distant landmasses, the waters below the surface patch are also filled with waste, making the problem of cleaning it up much greater.

Surveying The Patch

Covering a territory the size of three Frances, or 1.6 million km2, the patch is made up of debris consisting of abandoned fishing nets and plastics of all sizes, such as bags, six-pack rings, bottles, packing straps, and more. The debris does not make up a massive garbage island as it is floating freely, but in some parts, the garbage is extremely concentrated. Most of the patch is actually composed of microplastic debris, which is less than 5 mm in size, making it largely unnoticeable from the air. The mass of micro-plastics increased exponentially since studies were first conducted on the patch.

The area has been studied since the 1970s, but the urgency to do something about it became apparent in 2013, with studies geared towards deploying actual expeditions. In total, three major expeditions have been deployed to the Great Pacific Patch, starting with the Mega Expedition of 2015, which involved 30 ships and 652 surface nets that returned with over 1.2 million plastic pieces, concluding that far more large plastics were floating in the patch than expected.

Upon designing a new multi-level trawl, The Multi-Level Trawl Expedition was carried out later the same year, studying not only the extent of the buoyant plastic composition of the patch, but 11 layers of the water, as well. In 2016, the Aerial Expedition surveyed the larger plastics in the ocean by flying over an area of 311 km2 and returning with over 7,000 snapshots.

How Did It Form And What Is It Made Of?

Humans are the culprits of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, with ships having left behind fishing nets and dumping plastic waste into the ocean. Once the larger, more buoyant plastics get picked up by the ocean gyre, they float far into the waters, heading straight for the patch. Through the effects of sunlight, waves, and the breakdown by marine life, some disintegrate over time and become micro-plastics.

The main staples of the patch are hard plastics, including sheet, film, plastic lines, ropes, and fishing nets. Then, there are pre-production plastics, such as cylinders, spheres and disks, as well as fragments of foamed materials. While three-quarters of the mass consists of macro and mega objects with 92% of the debris being larger than 5 mm in size, by count, 94% of the total amount are micro-plastics.

Impact On Ocean Life

The three-dimensional garbage patch does not only spread out across the surface of the water but extends downwards to the bottom of the ocean floor. Being far offshore diminishes the problem in people's minds of the impact it has on marine life. Nevertheless, the three most impactful ways in which the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is destroying the natural ocean environment every day are through entanglement and ghost fishing, ingestion, and transportation of species.

Entanglement And Ghost Fishing

So-called "ghost nets" are the fishing nets left behind by fishers that continue to catch, injure, and often kill ocean dwellers including fish and small animals. Upon becoming entangled, the animal chaotically tries to break free only to be become increasingly trapped potentially injuring oneself in the process. Furthermore, an entangled animal has low chances of prolonged survival, as it is unable to hunt, feed or mate as it needs. 700 different species are victimized this way in their native environment, with 17% of them being on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List of Threatened Species.

Ingestion

A study concluded that 84% of the debris found in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch contained toxic chemicals, too much of which causes toxic build-up, internal injury, or even death upon digestion. According to the Ocean Cleanup organization, 74% of the diets of sea turtles living in such areas consist of plastic debris. Laysan albatross chicks from Kure Atoll and Oahu Island consume so much plastic that they are nearly halfway made up of the material and face extreme malnutrition. This problem affects not only the sea-dwellers, but the native birds that ingest microplastics along with their prey, or prey that has previously ingested the debris.

Transportation Of Species

Larger plastics, fishing nets, and other debris transport animals from one part of the ocean to another, potentially bringing invasive species into a vulnerable area. This includes, but is not limited to, plants and animals such as algae, barnacles, and crabs, which, if settled successfully, will reproduce to grow in population, affecting the ecosystem of an area.

Effects On Society

The economy also suffers from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The impact of the patch on the costs of tourism, fisheries, aquaculture and governmental clean-up are estimated to be from $6 to $19 billion USD per year. Larger objects get entangled in the propellers of ships, while the hidden debris under the water surface clogs the intakes and damages the ship's exterior, skyrocketing economic costs further.

Humans ingesting fish that has already ingested microplastics may become sick from the toxins, also known as the process of bioaccumulation. In reality, the costs are higher yet, as the above numbers do not include the healthcare expenditures for those affected, nor, perhaps the greatest cost of all, the depletion of marine life. With the costs already so high, it is no wonder that the situation is becoming urgent. However, it is much more than just the cost of the clean-up that stands in the way of eliminating the patch, but the difficulty of such task.

What Is Being Done And Future Prospects

As previously mentioned, much of the Garbage Patch is made of plastic and other materials that only disintegrate with time but never disappear. While fishing nets can be removed from the patch most successfully, much of the microplastic is impossible to detect with a naked eye. Furthermore, only the garbage on the surface of the water can be removed without potentially hurting the inhabitants. The rest is possible to remove only through ploughing the depths of the waters with a cleaning device, which would kill all of the inhabitants of the area.

Because the task to completely eliminate the patch is currently impossible, the problem will persist for the foreseeable future. Marine biologists and other scientists believe that the best way to deal with it starting now is by halting the growth of the patch by taking a proactive approach with preventative measures, including laws on dumping, shore clean-up to prevent the debris from floating further into the ocean waters, and removal of fishing nets from fishing expeditions.

While the technologies to safely and effectively combat the Great Pacific Garbage Patch are yet to be invented, it is important to become educated on the topic, to become aware of the facts, and the consequences of dumping waste into the ocean. Despite the difficulty of the task, many still have faith that since the human race is responsible for creating the problem in the first place, it can carry the solution.