Is The Panama Canal Going To Dry Up?

In the last few centuries, few manmade creations have had such a prolonged and impactful effect on global trade quite like the Panama Canal.

Its construction on the Isthmus of Panama took 10 years, creating a link between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. After it was finished, travel paths were vastly shortened, cutting down the time and money needed for shipping.

Today, the canal is used by thousands of ships every year and receives five percent of all goods shipped on the sea. It is a vital cog in world commerce and an important part of the complicated web of international trade.

However, the canal has faced a significant issue due to insufficient rainfall. This problem, exacerbated by climate change, has led to decreasing water levels in bodies of water that supply the canal. Consequently, this has increased waiting times for ships and restrictions, adversely affecting global maritime trade by limiting the movement of goods.

While the canal is not on the verge of running dry, there clearly is a problem that needs to be addressed. Efforts are in full swing to improve water conservation and find new solutions to keep the canal operating efficiently despite ongoing challenges. This situation with the Panama Canal exemplifies the vast, broad impacts of climate change on critical global trade infrastructure. One country's drought can affect the entire world.

Historical Significance of the Panama Canal

In the spring of 1904, the United States rolled up its sleeves to finish the job of building the Panama Canal. France was the first country to take a crack at creating this iconic waterway. It got further than planning, too, as they had started their operation in 1881, led by Ferdinand de Lesseps, one of the men responsible for the Suez Canal.

However, the French plan failed due to harsh working conditions, rampant diseases like malaria and yellow fever, and engineering challenges in the difficult terrain. Additionally, financial mismanagement and corruption led to bankruptcy, halting the project despite significant progress and investment.

So, the United States tried its hand next, led by President Theodore Roosevelt. The challenges did not end with the United States in charge. They had to develop innovative engineering solutions and figure out how to keep diseases like yellow fever and malaria from spreading.

In his article "Triumphalism and Unruliness during the Construction of the Panama Canal,” Paul Sutter said that a dedicated group called the “Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC)” led the project. They helped conquer these hurdles by implementing groundbreaking techniques and rigorous sanitation protocols. The ICC spearheaded extensive drainage systems and vaccination programs to combat the spread of diseases.

The monumental engineering project, which linked the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, was completed and officially opened on August 15, 1914. One of the most important features is the locks, which operate by raising and lowering ships between sea level and Gatun Lake, using a system of chambers filled and emptied with water.

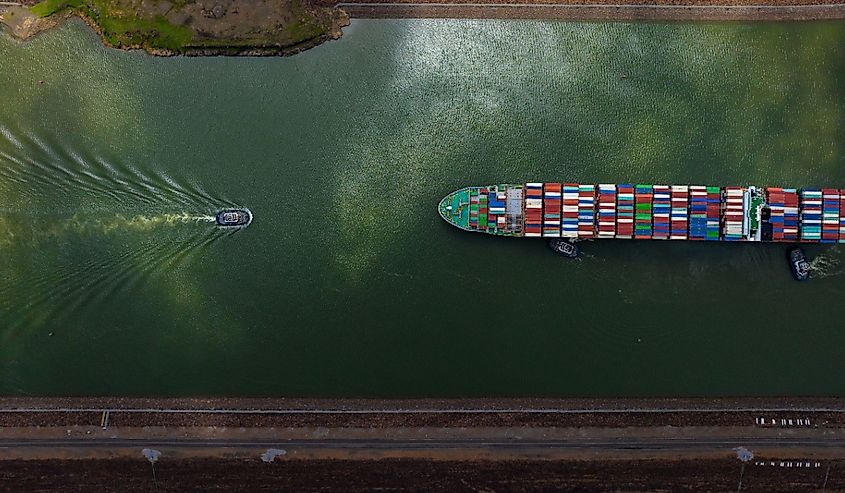

Since its creation, the canal has vastly improved the ease of how products move worldwide, making world economies more connected. Nowadays, over 14,000 ships pass through every year, compared to about 1,000 transits in 1915. In modern times, the canal is especially vital for moving goods between Asia and the Americas, acting like a watery bridge to get products from one side of the world to the other.

It is also interesting to see how a relatively small body of water has such a stranglehold on world commerce. The canal is not a monstrous waterway in terms of physical size. In reality, the engineering marvel is only around 50 miles from the two deepwater points, varying its width between 500 to 1000 feet.

After the project was finished and the years passed, unhappiness grew at home in Panama. Unrest was constant over displeasure with American ownership of the canal. According to Sue Vander Hook in her book, The Panama Canal, displeasure has been growing since the end of World War II. After the war, there was at least one riot about the Canal every decade.

This came to a head in 1964 when Panamanian students protesting to fly their national flag in the Canal Zone ended with violent clashes with U.S. forces, leading to around 20 Panamanian deaths. This event is now called Martyrs' Day in Panama. This accelerated a transfer of ownership, and on September 7th, 1977, U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Panama's Omar Torrijos shook hands on two huge deals. They were called the Panama Canal Treaty and the Neutrality Treaty, which ensured Panama had control over the canal by 1999 and guaranteed its neutrality for international maritime traffic.

Today, the Panama Canal Authority (ACP), an official entity within the Panamanian government, oversees all operations and is responsible for maintaining the canal and ensuring the smooth transit of vessels.

Current Situation and Reasons for Water Shortages

While smaller vessels can go through the canal alone, larger ships cannot navigate the entire canal independently. Electric locomotives, known as "mules," tow these ships through portions of the trip, and the entire transit, including wait time, can take up to a day.

In times of drought, the water level drops, allowing fewer ships through. If that happens, wait times start to increase, leading to a backlog of ships. Lately, the canal has faced significant problems due to a lack of rain which has dried up water bodies in the area. This has led to Gatun Lake, a major source of water for the canal, facing historically low water levels. This, then, has led to longer waits for ships and limits to how often large ships can pass through the canal.

According to the Woodwell Climate Research Center, Panama has been experiencing a dramatic drought since early 2023, exacerbated by a strong El Niño and continuing global temperatures.

Water shortages and water availability are no strangers to the Panamanian people. In her article "An Infrastructural Event: Making Sense of Panama’s Drought," Ashley Carse paints a country that has seen its twists and turns regarding water levels. She says that Panama was the fifth rainiest country in the world in 2014, but only one year later, due to El Niño-related reasons, drought struck the nation.

Many current water scarcity problems with the canal are linked to the water levels in Gatun Lake. The lake was created when they built a dam across the Chagres River to allow more accessible water for the canal, which was needed to make it function as intended. Now, the lake stretches over about 20 of the total 50 miles. Besides helping ships pass through, the lake guards the canal and ships from flooding. Plus, it holds water that can be used when rain levels dip.

So, the lake is doing a lot of heavy lifting for the canal, but the lake has struggled lately. Woodwell says the water levels in the lake, recorded in January 2024, were almost 6 feet lower than the previous year, a sizeable drop.

Due to the decreased water levels, ACP has had to reduce the number of ships passing daily. The daily traffic has dropped from 36 ships to around 31, and sometimes even fewer, depending on the severity of the situation. Additionally, they have restricted the size of ships allowed to transit the canal.

Despite these efforts, insufficient rainfall prevents the canal from refilling to its previous levels. Here, localized climate problems start to become a big issue for everyone worldwide. A lack of rain in this small region in Central America can affect the world over.

This ongoing issue raises concerns about the safety and reliability of this shipping route as climate change progresses.

Expanded Impact on Canal Operations

These sorts of problems, though, were not completely out of the blue.

In a 1999 article, "The Panama Canal: Danger Ahead," Marissa Mencher warned of impending threats. She linked local deforestation to the degradation of an irreplaceable watershed vital to the region and the canal. She explained that the El Niño conditions of 1983 and 1999 illustrate the consequences of neglecting local rainforests, exacerbating drought conditions. Combining these issues with rising global temperatures and frequent El Niño events has led to the current predicament.

Even further back, in his 1978 essay "Deforestation: Death to the Panama Canal," Frank Wadsworth warned about issues leading to water scarcity in the canal. This issue has long been anticipated and part of the public consciousness. Despite these warnings, the management of forested areas has only seen a slow change.

And the more studies are done, the more they support the positive influence of forests. In their study "Bundling Ecosystem Services in the Panama Canal Watershed," Silvio Simonit and Charles Perrings found that 37 percent of forested areas positively impact dry-season flows.

What these studies show is that the situation remains complicated and is more than just El Niño or just rising global temperatures or just deforestation. Calling it a perfect storm of bad circumstances might be an overstatement, but it is clear that multiple factors are driving the canal toward a dramatic tipping point.

The resultant restrictions on ships due to low water levels have led to cost changes. The restrictions are not trivial either; it has led to longer wait times, with some ships experiencing up to fivefold increases in waiting periods.

Such delays disrupt shipping schedules and logistics, affecting the timely delivery of goods across global markets. The reality of the market is that longer shipping times will result in higher operating costs. And when higher costs for companies start to spring up, it is not atypical for consumers to pocket the burden.

In fact, several shipping companies have started to add surcharges for going through the Panama Canal. For example, MSC has announced a surcharge of $297 per container for routes from Asia to the US East Coast and Gulf, effective December 15, 2023. Additionally, Hapag-Lloyd and Ocean Network Express (ONE) have introduced surcharges of $260 and $145 per container, respectively.

If drought conditions persist, the risk of future disruptions increases. Continued low rainfall could necessitate further reductions in transit capacity, which would have severe repercussions for global shipping efficiency.

Global Implications

The World Trade Report 2022 highlights climate change as a driving force of ongoing transformations, noting rising temperatures and extreme weather can lead to productivity losses and disruptions in supply chains.

The challenges of climate change are evident in the operational constraints of the Panama Canal. The reduction in ship traffic is coupled with new surcharges, requiring vessels to either pay a prepaid booking fee or bid at ACP auctions.

This one-third capacity decrease is expected to significantly reshape seaborne trade flows, potentially affecting around 100 million tons of cargo, or approximately 35 percent of the total cargo that passed through the canal in 2022. As the canal's capacity is reduced, ships are increasingly rerouted to alternative, longer routes such as the Cape of Good Hope and the Suez Canal.

According to the UN Trade and Development, container freight rates on Asia-Pacific to Europe routes have risen sharply since November 2023. Some companies may invest in larger fleets suited for alternative routes like the Suez Canal, which can accommodate larger vessels. We have seen this, too, since the Suez Canal Authority has reported a traffic boost of 12 percent since 2020 because of the issues facing the Panama Canal.

This shift extends transit times and escalates fuel consumption and costs, complicating logistics and supply chain management across industries. For instance, a typical transit through the Panama Canal takes about eight to twelve hours, whereas rerouting via the Cape of Good Hope can add up to two or three weeks to the journey. This extension is a massive increase in fuel consumption.

Studies show when ships go around the Cape of Good Hope instead of taking the Panama Canal, they use about 25 percent more gas. This means they end up releasing more pollution, and it costs more to run the ships. This is an important detail because it makes shipping more expensive and harms the environment, affecting how we buy and sell things worldwide.

For instance, Maersk, which is one of the biggest companies for moving goods by sea, said it costs them 10 percent more to operate because of longer trips. Usually, when companies spend more money, people who buy the goods end up paying more, too.

The Panamanian People

When discussing the economic effect of trade, the local people affected by the drought can be overlooked. It is important to focus on their experiences.

The Panama Canal's current water issues impact local communities and the region's economy. The canal supports thousands of jobs in Panama, making it a vital source of employment.

With reduced canal operations, many workers face potential job insecurity and increased workloads as efforts to manage water resources intensify. Local shops, especially those involved in moving goods, sending packages, and travel, are finding it hard to make money.

According to the Panama Canal annual report, it brings in about $2 billion yearly from fees like tolls, which is a big boom to the country's economy. So if we start to see continued disruptions in canal operations, it will directly affect revenue flow, leading to impacts on public services and infrastructure investments in the region.

Moreover, the canal's water issues have led to restrictions on freshwater usage for surrounding communities. Almost 2 million people living in the Panama City area use water from the same sources the canal uses. Because of long dry spells and efforts to save water, there is now even stricter control over water use, which affects everyday life and farming.

Farmers who need steady water for their plants are getting less production from their crops. This isn’t great for the people or the country's food situation. The World Bank says that farming in Panama makes up about 6.3 percent of the country's earnings and gives jobs to about 15 percent of the people in the country.

So, the water shortage is not just a logistical challenge on a monetary level, but a human health challenge, impacting jobs, local economies, and the daily lives of millions in the region.

The Road Ahead

In response to the drought conditions affecting the Panama Canal, ACP has developed a comprehensive approach to maintain its operational sustainability.

Central to their strategy are the water-saving basins, an innovative system that recycles large portions of water used during each lockage. This will also significantly reduce the dependence on Gatun Lake. Additionally, the ACP occasionally imposes draft restrictions, limiting the depth at which vessels can transit the canal.

This decreases the water required for each vessel's passage, conserving vital water resources. Another plan would see the ACP embrace scheduling adjustments, strategically planning the timing and number of vessel transits to maximize water efficiency.

In the aforementioned essay, Wadsworth argues that the only solution is to restore the natural watersheds that come from the surrounding forests and that no stand-alone manmade solutions will be enough. The ACP is trying to do this by working with residents to plant more trees, especially with the help of coffee farmers. By doing this, they hope to reduce soil erosion and retain more water in the ground.

They have also paused creating electricity at the Gatun Lake plant to help retain water in reserve. These steps are to keep the canal up and running and ensure the people of Panama can withstand future heat events and drought. The shipping world might also need to consider other paths or change how it handles logistics to avoid problems from the canal's limits.

Outside of the efforts of the ACP, other organizations from around the world have stepped up. Here are just some of the organizations helping to deal with the issue.

The World Bank

The World Bank has been helping with water management jobs in Panama. They invest money into expanding the use of the Panama Canal, adding water-saving tricks and new tech to use water more effectively. They have also been leading projects to help manage water resources better in areas around Panama.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Reforestation Efforts

The UNDP has been working with locals and the government in Panama to plant more trees around the Panama Canal area. They plan to bring back the area's original foliage and forests, make the water cycle work naturally, and help the land handle drought better.

Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) Infrastructure

The IDB has put its efforts into creating new ways to store water for future usage and ensuring current methods are more sound and sustainable.

The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI)

In collaboration with the ACP and other entities, the STRI conducts research on the nearby watershed. This research includes monitoring ecological changes, studying the impacts of reforestation, and developing strategies for water sustainability.

These projects are crucial during periods of limited water availability, ensuring that the canal continues to function effectively while managing the challenges posed by drought conditions.

In Conclusion

Ever since it was built, the Panama Canal has completely changed trade routes around the world. But now, it is facing challenges because a lack of rain has drained the canal of much-needed water, tied to changes in our climate and El Niño weather conditions.

This situation shows how climate change at a local level can impact crucial infrastructure on a global level. Lower water levels in Gatun Lake have led to delays and limited the size of ships passing through the passageway.

In response, the ACP and other governing bodies have worked hard to find solutions, such as saving water and improving infrastructure. However, global shipping might need to find other routes or improve logistics to cope with these changes.

While the situation can seem dire when it looks like the canal is drying up, cooperative efforts are aiming to ensure that the Panama Canal continues to thrive and that its people are able to withstand future drought conditions.

Works Cited

Acciaro, Michele. "Climate Change Adaptation in the Panama Canal." Climate Change and Adaptation Planning for Ports, Routledge, 2015, pp. 204-225.

Autoridad del Canal de Panamá. "Annual Report." Panama Canal, https://pancanal.com/en/maritime-services/annual-report/.

Briginshaw, David. "China-Europe Rail Freight Traffic Up 27% in First Seven Months of 2023." International Railway Journal, 23 Aug. 2023, www.railjournal.com/freight/china-europe-rail-freight-traffic-up-27-in-first-seven-months-of-2023/.

Carse, Ashley. “Nature as Infrastructure: Making and Managing the Panama Canal Watershed.” Social Studies of Science, vol. 42, no. 4, 2012, pp. 539-63. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41721341.

Carse, A. "What Comes after the Conquest of Nature?" Modern American History, vol. 7, no. 1, 2024, pp. 136-140. doi:10.1017/mah.2024.9.

“Climate Change and International Trade.” International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, vol. 5, no. 3, 26 July 2013, https://doi.org/10.1108/ijccsm.2013.41405caa.009.

“Customer Advisory - Panama Canal Contingency Surcharge | ONE United States.” Us.one-Line.com, us.one-line.com/news/customer-advisory-panama-canal-contingency-surcharge.

Department Of State. The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs. “Panama Canal Treaty of 1977.” 2001-2009.State.gov, 2001-2009.state.gov/p/wha/rlnks/11936.htm#:~=President%20Jimmy%20Carter%20and%20Panamanian.

Dierker, David, et al. "How Could Panama Canal Restrictions Affect Supply Chains?" McKinsey & Company, 19 Jan. 2024, www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel-logistics-and-infrastructure/our-insights/how-could-panama-canal-restrictions-affect-supply-chains.

Diplomat, The Water. “International Trade Rerouted as Panama Canal Cuts Traffic due to Drought.” The Water Diplomat, 3 Dec. 2023, www.waterdiplomat.org/story/2023/12/international-trade-rerouted-panama-canal-cuts-traffic-due-drought.

Feingold, Spencer, and World Economic Forum. “Drought at the Panama Canal Disrupts Global Trade.” World Economic Forum, 22 Aug. 2023, www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/08/drought-at-the-panama-canal-poses-unprecedented-challenges-to-global-trade/#:~:text=URL%3A%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.weforum.org%2Fagenda%2F2023%2F08%2Fdrought.

“How Could Panama Canal Restrictions Affect Supply Chains? | McKinsey.” Www.mckinsey.com, www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel-logistics-and-infrastructure/our-insights/how-could-panama-canal-restrictions-affect-supply-chains.

Institution, Smithsonian. “Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.” Smithsonian Institution, www.si.edu/about/tropical-research-institute.

Mencher, Marissa. “The Panama Canal: Danger Ahead.” The Journal of Environment & Development, vol. 8, no. 4, 1999, pp. 407-15. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44319471.

“Navigating Troubled Waters: Impact to Global Shipping Disruptions | PreventionWeb.” Www.preventionweb.net, 23 Feb. 2024, www.preventionweb.net/news/navigating-troubled-waters-impact-global-trade-disruption-shipping-routes-red-sea-black-sea.

Our World in Data. “Share of GDP from Agriculture.” Our World in Data, 2021, ourworldindata.org/grapher/agriculture-share-gdp.

“Panama.” Drought-Portal, www.fao.org/in-action/drought-portal/preparedness/vulnerability-and-impact-assessment/national-case-studies/panama/en.

“Panama Archives.” FocusEconomics, www.focus-economics.com/countries/panama/.

“Panama Canal Expansion: A Smart Route for Boosting Infrastructure in Latin America.” World Bank Blogs, blogs.worldbank.org/en/voices/el-canal-de-panam-una-nueva-ruta-para-impulsar-infraestructura.

“Panama Canal Surcharge - Trade from South Africa, Mozambique, Namibia to South America West Coast.” MSC, www.msc.com/en/newsroom/customer-advisories/2023/december/panama-canal-surcharge-trade-saf-mozambique-namibia-to-sawc.

“Panama Canal Watershed Restoration | NDC Partnership.” Ndcpartnership.org, ndcpartnership.org/knowledge-portal/good-practice-database/panama-canal-watershed-restoration.

“Protecting the Canal’s Water Now for a Sustainable Future.” Autoridad Del Canal de Panamá, 28 Jan. 2020, pancanal.com/en/protecting-the-canals-water-now-for-a-sustainable-future/.

“Responsible Forestry in Panama.” Www.wwfca.org, www.wwfca.org/en/?97460/Responsible-forestry-in-Panama.

Rodríguez, Roberto. “Fiscal Year 2024 Update.” Autoridad Del Canal de Panamá, 30 Sept. 2023, pancanal.com/en/fiscal-year-2024-update/.

Ruiz, Sarah. “Drought, Climate, and the Panama Canal.” Woodwell Climate, 20 Feb. 2024, www.woodwellclimate.org/drought-panama-canal-7-graphics/.

Simonit, Silvio, and Charles Perrings. “Bundling Ecosystem Services in the Panama Canal Watershed.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 110, no. 23, 2013, pp. 9326-31. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/42706613.

Sutter, Paul S. “Triumphalism and Unruliness during the Construction of the Panama Canal.” RCC Perspectives, no. 3, 2015, pp. 19-24. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26241327.

“UNDP Regional Hub in Panama.” UNDP, www.undp.org/latin-america/about-us/undp-regional-hub-panama.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. “Navigating Troubled Waters: Impact to Global Trade of Disruption of Shipping Routes in the Red Sea, Black Sea and Panama Canal.” Prevention Web, 23 Feb. 2024, www.preventionweb.net/news/navigating-troubled-waters-impact-global-trade-disruption-shipping-routes-red-sea-black-sea.

Vander Hook, Sue. Building the Panama Canal. ABDO, 1 Jan. 2010.

Wadsworth, Frank. Deforestation: Death to the Panama Canal. U.S. Strategy Conference on Tropical Deforestation, 1978, U.S. Dept. of State and U.S. Agency for International Development, Washington.

Worthington, William E, and Aileen Cho. “Panama Canal | History & Facts.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 22 Jan. 2019, www.britannica.com/topic/Panama-Canal.

Zubieta, Alberto Alemán, and Karen E. Breiner-Sanders. “The Panama Canal: On the Move in the 21st Century.” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, vol. 3, no. 2, 2002, pp. 43-50. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43134049.