How Bad Was The Spanish Inquisition?

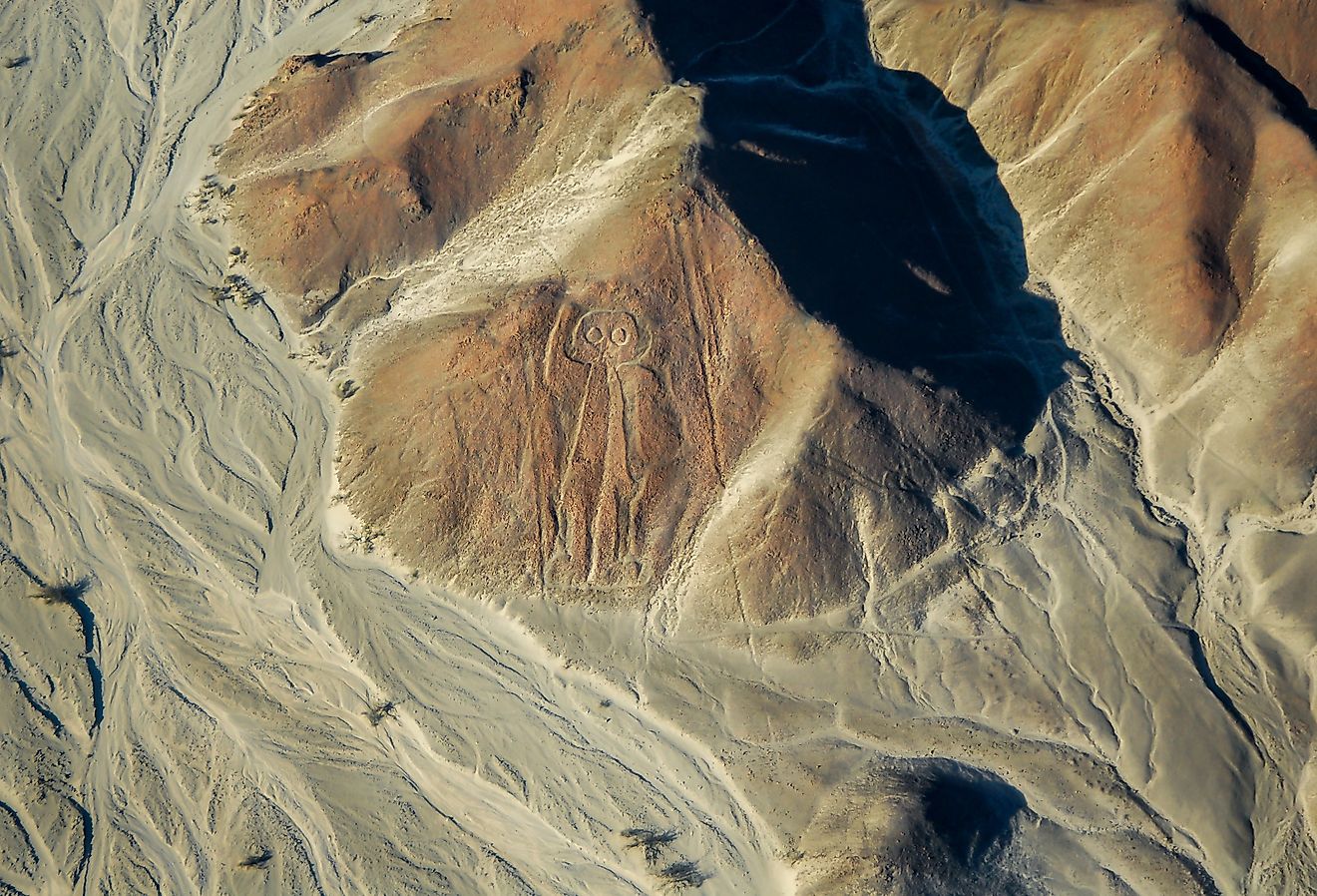

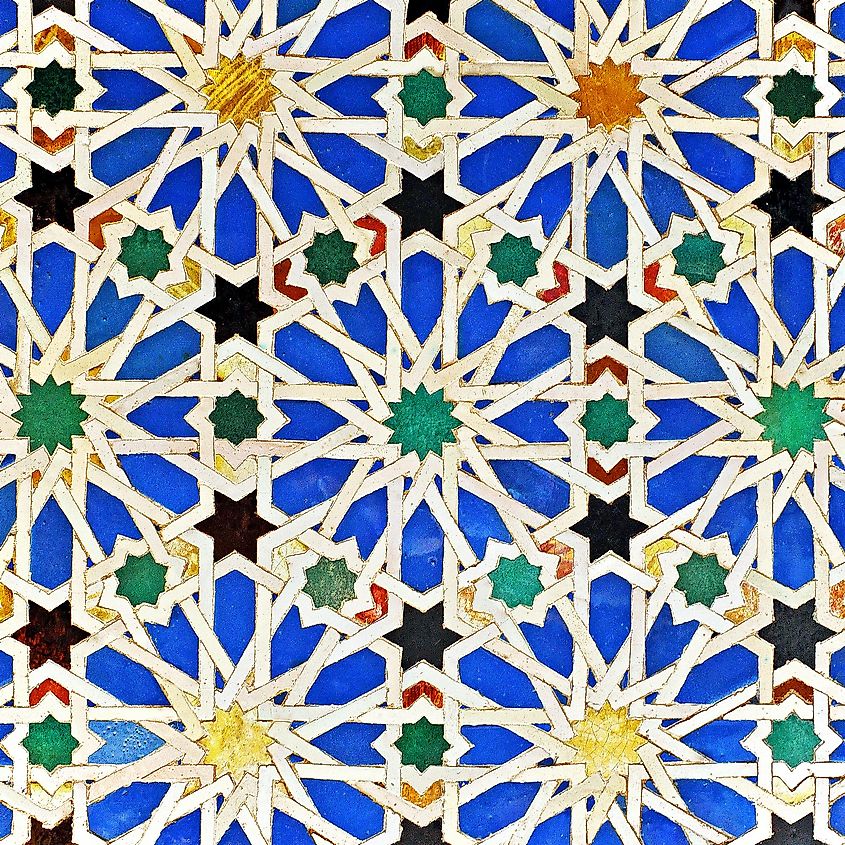

The Spanish Inquisition was established in the 15th century in the final days of the Reconquista. As the Christian Spaniards pushed out the last remnants of Muslim rule in the Iberian Peninsula, distrust, suspicion and outright hostility towards other faiths were never higher.

In English-speaking, largely Protestant, Western nations such as the United States, the Spanish Inquisition is usually portrayed as a uniquely bloodthirsty and violent organization that gleefully killed, tortured, and imprisoned hundreds of thousands of people deemed to be a threat to the Catholic faith. This belief has endured for centuries and is often expressed in various forms of media, namely Hollywood movies and television shows. But is this representation of the Spanish Inquisition warranted?

Formation Of The Inquisition

It is important to remember that the Spanish Inquisition was not the first organization of its kind in Europe or even Spain. All across Medieval Europe, various agents either sent by a secular leader or religious figureheads were tasked with making sure its citizens were living what was considered to be good Christian lives.

In the year before the success of the Reconquista, most inquisitors were sent to crack down on heresy which originated from within the Christian faith namely the Cathars and Waldensians who sprung into existence during the 12th and 13th centuries.

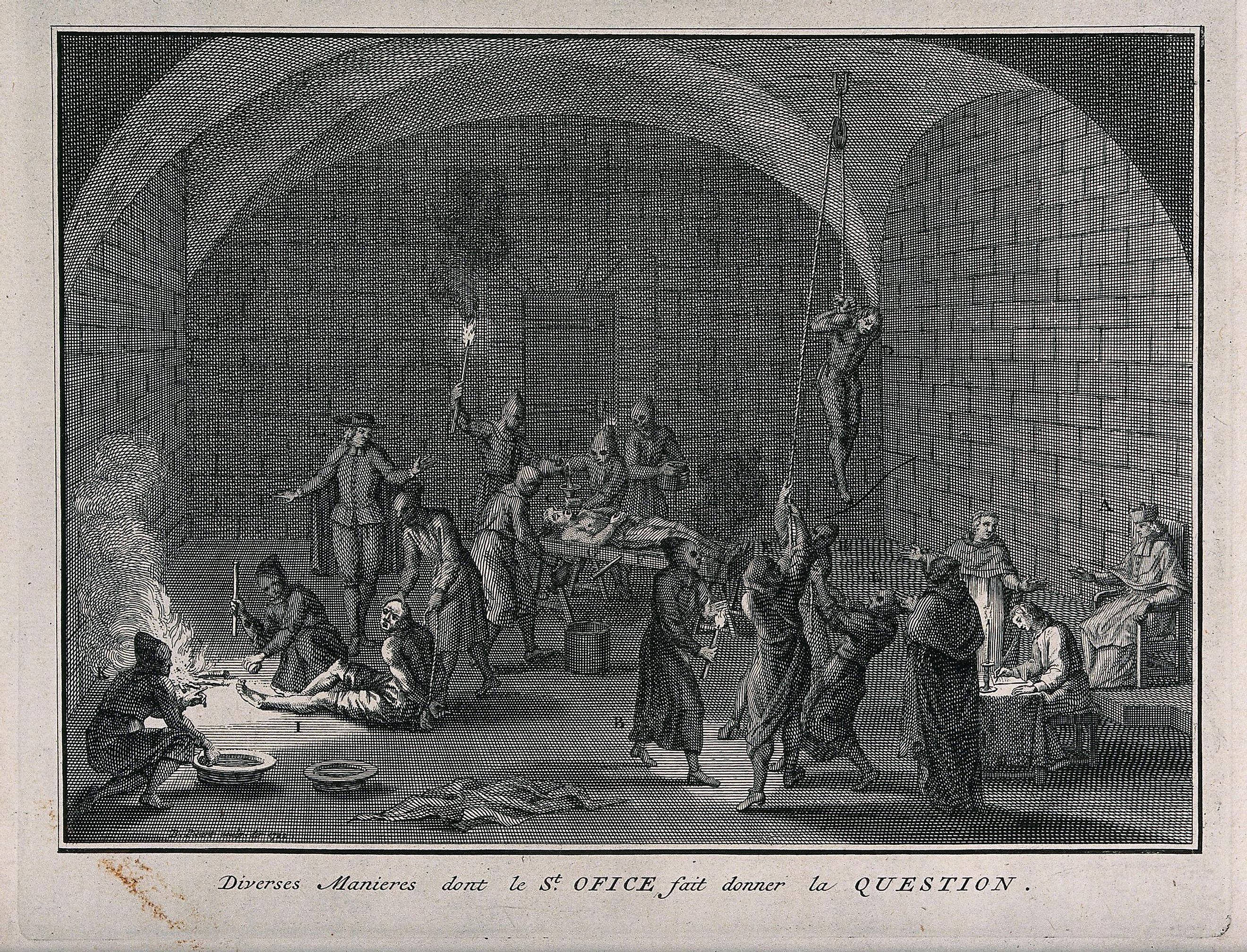

Despite common perception, inquisitors often announced their visit weeks in advance rather than sneakily infiltrating a town from the inside to weed out any potential heretics. Once they arrived they would publicly allow anyone who had committed a crime against the church a chance to confess and repent. Those who came forward were usually punished by being sent on pilgrimage, paying a fine, or being whipped. Those who did not were investigated further. It was at this stage of the investigation that things got messy.

What made the Spanish Inquisition so notable is that in the wake of the reconquest of Spain, the Spanish government and church now found itself ruling over significant Jewish and Muslim populations. Combining this new and sudden influx of minorities with a religious zeal that had been a large driving factor behind the Reconquista, made for a particularly intense inquisition.

Forced Conversions and Deportations

In the middle of the 15th century, it was often Jews who found themselves in the crosshairs of both the Spanish government and the Inquisition. Often working in tandem, Jews were subjected to forced conversions. Those who refused to give up their faith were either deported, tortured, or killed. The Muslim population in Spain faced a similar fate decades later.

It is widely accepted that many of these converts were not sincere and continued to practice their faith in private and only presented a Catholic aesthetic when out in public. These new "converts" or conversos were still viewed with suspicion by many Spaniards and faced harassment from authorities on a regular basis.

As a result of these new policies, most of Spain's Jews and Muslims fled to North Africa, namely Morocco to escape persecution. With most of these foreign threats now taken care of, the Spanish Inquisition turned its focus on other Christians.

The Height Of The Inquisition

It is no coincidence that the height of power that the Inquisition held coincided with the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century. In the early 1500s new sects of Christianity were popping up across Europe, most of whom rejected the authority and legitimacy of the Catholic Church. While these new branches of Christianity, namely Calvinism and Lutheranism were most popular in Germany, Northern Europe, and England, there were large amounts of Spaniards who also showed considerable interest in this new flavor of the faith. This was, of course, something that the Spanish Inquisition could not allow.

Early Protestant leaders were often thrown in prison or deported from Spain altogether. This method was the most common but violence was not off the table. If someone did not repent or kept returning after being deported public humiliation, torture, and even death were deemed acceptable.

Protestants were not the only targets of the inquisition but so were other Catholics. Many high-ranking Catholic officials were arrested and tried for heresy as well. It might be surprising to learn that some of these Catholic officials were apprehended as a result of the accusations being made by Protestants that the church had lost its way and become corrupt. The arrests of these Catholic leaders were especially prominent in Rome, which had the most professional and effective inquisitions across Europe.

Who Was An Inquisitor?

Inquisitors tended to be some of the most well-respected and revered people within Spanish society. They often hailed from established religious orders that already had a stellar reputation amongst the common folk. Inquisitors were often educated and seen as reliable figures that established law and order.

The courts in which the inquisitors operated were separate from secular courts. The inquisitorial courts tended to be much more lenient than their secular counterpart and stressed the use of evidence to get a conviction. This "evidence" was often poorly put together eyewitness testimonies but this was still considerably better than what was afforded to those at the mercy of a king or emperor.

Executions were not usually the end goal of an inquisitor. The primary concern from an inquisitor's point of view was to save the accused soul and set them back to what they deemed as a holy and righteous lifestyle. Killing someone, especially a leader of a heretical movement meant that they had failed in what they had set out to do and could also make a martyr out of the executed. The most common form of violence that an inquisitor would use was torture to force a confession. Although this was rare and only used as a last resort.

When the Spanish Inquisition tortured someone in their captivity they did so in a very controlled fashion. While the idea of "moderate torture" might seem laughable today, by its contemporary standards, the torture the Spanish Inquisition participated in was quite progressive. Torture of prisoners was only allowed for 15 minutes and had to be done in the presence of a doctor. Any torture that resulted in long-lasting or permanent injury was outlawed. The torture would stop if the prisoner confessed to what they were accused of or if the doctor expressed concern that the prisoner might be at risk of dying.

If anything, the religious courts were often seen as being too soft on the accused. It was often the will of the secular authority and commoners alike to issue harsher sentencing. It was not unheard of for supposed heretics to be killed by lynch mobs before they ever saw the inside of the courtroom in fear that "proper justice" would not be served by the Inquisition.

Protestant Rivalries and Modern Perception

Much of the modern perception of the Spanish Inquisition stems from English propaganda that was created during the 1500s. During the Protestant Reformation England was one of the first nations to break away from the Catholic Church and instead follow the Church of England. This resulted in terrible relationships with Catholic nations such as France and Spain.

This bitter rivalry was only made worse when both nations clashed with one another across European battlefields and in the New World. As a result, the English government painted Catholicism particularly the Spanish Inquisition as an especially cruel and evil institution that routinely carried out public executions for the smallest of infractions.

These negative assumptions about Catholicism would be later used to persecute Catholics within the United Kingdom and Ireland in the coming centuries. This campaign of misinformation was so powerful that many people to this day still hold views that originate from this time period in English history.

In truth, the total death toll attributed to the Spanish Inquisition across its entire existence (1480 - 1826) was between 3,000 and 5,000 people. It goes without saying that anyone who was killed as a result of these inquisitions was terrible tragedy but it is a far cry from some of the figures which suggest that hundreds of thousands of people died as a result of overzealous fanatics.

The Spanish Inquisition was by no means something to be celebrated but it also was not the apocalyptic mass murder campaign that it is often portrayed as. In many ways, at least when considering what the alternative was at the time, the Inquisition was much more lenient and forgiving than the secular authorities.

While certainly brutal by our standards today, the Inquisition was ahead of its time in evidence collection and court proceedings, something that would later be borrowed by secular courts centuries later.