Napoleonic Wars and the Emergence of Modern Nationalism

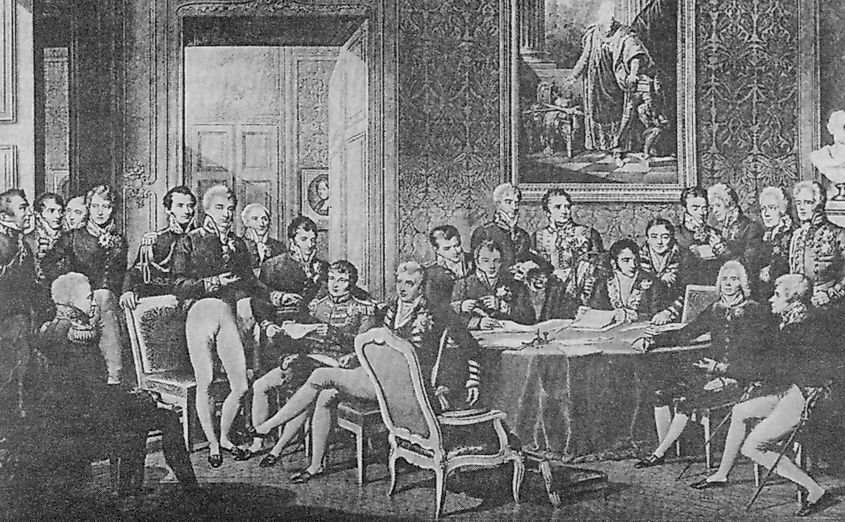

Napoleon Bonaparte changed the fate of Europe like few others. As France emerged from the bloody and divisive French Revolution, Napoleon rapidly ascended to power and had his eyes on the European continent, hungry to expand French dominance. As the Emperor of France, he undertook a massive offensive on the continent, and Europe underwent substantial changes as a result of Napoleon’s military campaigns and the restructuring of states and nations. After the war and France’s gradual defeat, the subsequent Congress of Vienna in 1814-15 molded and shaped the boundaries of Europe. In the case of modern-day Ukraine, their territory was divided among various empires and powers, including the Russian Empire. During the Napoleonic Wars and after the distribution of lands to new and old countries alike, there was a growing awareness of a Ukrainian identity. The desire for self-determination among parts of the Ukrainian population was starting to blossom. Subsequently, inhabitants of these regions began to express a shared sense of national identity and advocate for the safeguarding of Ukrainian cultural heritage.

Though Ukrainian nationalism can't be singularly attributed to the Napoleonic Wars, these conflicts contributed significantly towards stirring up national self-awareness in Ukraine. The result of the wars and the rising scope of nationalism laid the groundwork for the emergence of a strong Ukrainian identity in the decades to follow.

The Three Wars

War of the First Coalition

Without the context of the greater European theatre, the rise of nationalism in Ukraine lacks some context. Napoleon Bonaparte's rise to power is a complicated series of complex events, from revolutions to European warfare. It is easiest to break it down by the major events that helped create Emperor Napoleon.

First off was the French Revolution, a transformative period of political and social upheaval triggered by widespread discontent and social inequality. It didn’t just change France's political landscape, it shattered it. The revolution led to profound societal changes and influenced politics all over the world. As the Bourbon monarchy, including King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette, faced incarceration and execution, Napoleon was subtly yet steadily advancing his military status. He rose to fame during the French Revolutionary Wars. These conflicts sprung up as a direct result of this new revolutionary spirit burning in France. Countries around France, monarchies just like the Bourbons, were a bit worried.

While the newly formed administration in France wanted to spread its newly founded principles, it also initiated aggression. The French monarchy's removal and subsequent founding of the French Republic made 1792 an important year. It was also the year when France proclaimed war on Austria. Later in the same year, France made a bold proclamation that they would assist any citizens rallying against their respective government. The new French government believed that a war would help consolidate power and unite the still chaotic nation. They saw Austria as a symbol of the old regime and a potential threat to the revolutionary government. In response, a coalition of European powers rose up, concerned about these revolutionary ideas spreading any further. Napoleon was appointed as a commander, and under his watch, the French scored success against both Austrian and Italian armies.

Upon his return to France from the battlefield, he discovered that he held sway and influence. He was designated as the Chief of Interior Military Forces—and this position heightened his interest and insight into national politics. The coalition against France was barely holding together. In a short time, they fragmented due to unfocused interests. In 1797, the Treaty of Campo Formio was negotiated by Napoleon Bonaparte. It redrew European borders, as Austria ceded Belgium and the left bank of the Rhine to France. The treaty temporarily stabilized post-revolutionary Europe, but it didn’t last long.

War of the Second Coalition

In 1798, French officials came up with a plan to assert a French presence in Egypt. With Napoleon leading, the Egyptian expedition began wonderfully, capturing Malta, Alexandria, and the Nile Delta. The political climate in France was shifting and impossible to foretell. The peak of this domestic conflict came with a coup d'état towards the end of 1799. Napoleon had prearranged his comeback and made it back to Paris by October. The coup, known as the 18–19 Brumaire, saw the resignation of the directors and the dispersion of legislative councils. It ushered in a new government, the Consulate, with three consuls— one of which being Bonaparte. While this was happening, Emperor Paul I of Russia, Catherine the Great's son, was furious at France's occupation of Malta. He responded by sending fleets to capture French islands while assembling a new alliance, which grew to include Britain, Austria, the Ottomans, and more.

The myth of Bonaparte's unbeatable power was fragmented after his defeat at The Battle of the Nile, acting as a catalyst for another European coalition to form. Despite this, the coalition did not have much unity and fell apart. The Armistice of Treviso between France and Austria led to a temporary cessation of hostilities, and the Treaty of Florence between France and Naples led to French control over parts of Italy. Like the First Coalition, poor communication and a lack of unity doomed the alliance from the start.

Napoleon embarked on a successful military campaign in Italy, defeating the Austrians at the Battle of Marengo in June 1800, which led to the Treaty of Lunéville in 1801. These diplomatic agreements and military successes weakened the unity of the Second Coalition, and various members began seeking separate peace terms with France. Ultimately, the Treaty of Amiens in 1802 marked a formal peace between France and Britain, officially ending the hostilities of the Second Coalition.

The Napoleonic Wars

Peace in Europe would not last. At best, the Treaty of Amiens was fragile. A sense of shared suspicion remained between France and Britain. Amidst growing fears sparked by Napoleon's ambitions, Britain declared war on France in 1803.

In the next year, Napoleon assumed his self-appointed role as Emperor of the French during a splendid Parisian ceremony. It solidified his status at the forefront of French political affairs and established foundations for broadening European influence. By 1805, things escalated in European warfare with the Battle of Austerlitz, where Napoleon's troops accomplished victory over the Third Coalition, mostly made up of Austria and Russia. This led to the reorganization of territorial boundaries in favor of France. Soon after, the Third Coalition fell apart.

The Fourth Coalition emerged in response to Napoleon's growing European dominance and aggressive expansionist policies. It was comprised primarily of Prussia, Russia, Saxony, and Sweden, with Britain as its key naval and financial supporter. Tensions escalated when Napoleon's forces occupied the northern German states and imposed economic restrictions through the Continental System, aiming to isolate Britain economically. In 1807, Napoleon routed Russia in two successful battles, leading them to sign the Treaty of Tilsit. The treaty aimed to carve up Europe into two spheres of influence, Russia and France.

Between 1807 and 1812, Napoleon's France dominated Europe, creating satellite states and enforcing the Continental System to weaken Britain. Napoleon's attempts to enforce his policies strained relations with Russia. In 1812, his attention would shift to invading Russia, and disaster followed. The campaign in Russia was a complete mess for the French, with the harsh Russian winter and logistical challenges resulting in catastrophic losses for the French forces.

The defeat in Russia marked a significant turning point in the Napoleonic Wars. It weakened Napoleon's hold on Europe and gave confidence to other members of Europe. Maybe Napoleon could be defeated. In fact, the end was nearing for Napoleon.

In 1813, the Battle of Leipzig dealt a decisive blow. The coalition forces scratched away at France’s power. By the next year, the coalition had captured Paris, forcing Napoleon's abdication and subsequent exile to the island of Elba. Europe hoped for a lasting peace. However, Napoleon's return in 1815, known as the Hundred Days, was one last hurrah. This final period of Napoleon was brief and culminated in the Battle of Waterloo, where one last coalition dealt a final blow to Napoleon's ambitions.

Rise of European Nationalism

If the subject is Russia and Ukraine and their ongoing relationship, why are we talking about Napoleon and France? One of the greatest offshoots to emerge from these wars was a series of nationalist movements burning across Europe. Both the French Revolution and Napoleon’s march across Europe helped ignite a burning passion for people’s homeland, whether physical or metaphorical.

Several instances of patriotic emotions came directly from the war. Napoleon's conquests led to the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, inadvertently fostering German nationalism. The subsequent creation of the Confederation of the Rhine laid the groundwork for German unification by consolidating numerous German states. After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Poland was divided once again among Russia, Prussia, and Austria, which fueled Polish nationalism and aspirations for independence. It also united the former Austrian Netherlands with the Kingdom of the Netherlands under Dutch rule. Less than two decades later, the Belgian Revolution erupted, resulting in the independence of Belgium. All of these are examples of nationalism coming to the forefront in Europe.

Ukrainian Nationalism and Identity

Something very distinct happened in Russian lands during the Napoleonic Wars. According to Serhii Plokhy, author of The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine, Russian imperial journals started to print patriotic poems in Ukrainian. While usually Russia followed a policy of trying to unite its people under the Russian language, special situations call for a special response.

The Russian Empire was looking for ways to rally all its subjects, including Ukrainians, against the common threat posed by Napoleon's forces. The response to the wars differed in neighboring Poland, where Napoleon was viewed as a liberator, presenting a notable contrast, since with Ukrainians, it was the opposite. Modern nationalism was beginning to grow due to a strong anti-Napoleon sentiment, and that included Ukraine.

During the closing decades of the 1700s, parts of modern-day Ukraine were absorbed by the Russian Empire. Frequently referred to as "Little Russia", this term was used for these newly annexed areas. It also hinted at a disparity between the regions primarily speaking Russian and those parts of the empire with more ethnic variety. Since the Treaty of Tilsit in 1807 expanded Russia into parts of modern-day Ukraine, it increased Russian influence in the region and contributed to the spread of the Russian language and culture. However, when the Ukrainian national awakening kicked off during the 19th century, locals began discouraging the use of "Little Russia". The reason was that it stood symbolic of Russian imperialist supremacy and seemed derogatory towards unique Ukrainian self-perception. Instead of using a term that was saying a version, or part of Russia, Ukrainians began to use terms like "Ukraine" and "Malorossiya" to assert their own distinct national identity.

As historian Alexei Miller in his article “Shaping Russian and Ukrainian Identities in the Russian Empire During the Nineteenth Century” puts it, many used the terms Great Russians and Little Russians to describe Russian and Ukrainian people. The terms implied differences between regions instead of the difference between nations. So, there was a clear divide between the ‘us’ and ‘them’ in Russia and something the Ukraine citizens were feeling at some level. In 1816, only a year after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the first literary almanac in Ukraine appeared. While it was still written in Russian, it accepted submissions in Ukrainian, and many of its authors talked about Ukrainian issues.

One of the interesting events on the Ukrainian road to seeing itself as a nation was spurred on by a Polish Uprising. While the uprising did not directly spread to Ukrainian-majority areas, the broader consequences of the insurrection, such as increased Russian repression and surveillance, affected these regions as well. The Russian Empire put down the uprisings and immediately saw a threat to Russian identity and the Russian sense of nationalism. According to Plokhy, this conflict called into question the loyalty of the Ukrainian peasants. In response to the Polish uprisings, the imperial powers sought to cement Russian ideas of nationalism. They built a university in Kyiv whose most important purpose was to promote Russian identity. The battle for the spirit and identity of Ukraine had truly begun.

Key Takeaways

The military and diplomatic initiatives of Napoleon Bonaparte during the Napoleonic Wars led to vast transformations across Europe, both territorially and politically. These changes altered the entire makeup of the continent. Napoleon’s military exploits and the subsequent reconfiguration of Europe’s landscape spurred regions like Ukraine to cultivate a more potent national identity. The transition was fueled by both state restructuring and sweeping ideological changes that defined the period.

During this time, Ukrainian nationalism developed as a reaction to the transformations sparked by warfare and the fluctuating balance of power in Europe. The effect these events laid the foundations for future movements seeking self-governance and safeguarding cultural legacies, not solely within Ukraine but throughout the entire continent. As the 19th century progressed, the effects of the Napoleonic Wars continued to shape how Europe viewed itself. While the concept of Ukrainian nationhood was still fresh, the roots had dug in, and soon, the movement would see real, tangible growth.

Works Cited:

Charques, R.D. Between East and West: The Origins of Modern Russia: 862 - 1953. Pegasus Books, 1956.

Johnson, Paul. Napoleon: A Life. Penguin Group, 2014.

Kohn, Hans. “Napoleon and the Age of Nationalism.” The Journal of Modern History, vol. 22, no. 1, 1950, pp. 21–37. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1875877.

Miller, Alexei. “Shaping Russian and Ukrainian Identities in the Russian Empire During the Nineteenth Century: Some Methodological Remarks.” Jahrbücher Für Geschichte Osteuropas, vol. 49, no. 2, 2001, pp. 257–63. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41053013.

Reid, Anna . Borderland : A Journey Through the History of Ukraine. 2nd ed., Basic Books: Member of The Perseus Book Group, 2014.

Plokhy, Serhii. The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine. 2nd ed., Basic Books, 2022.

Plokhy, Serhii. Lost Kingdom: The Question For Empire and the Making of the Russian Nation. 1st ed., Basic Books, 2017.

Rapport, Mike. The Napoleonic Wars: A Very Short Introduction. 1st ed., Oxford University Press, 2013.

Roberts, Andrew. Napoleon the Great. 1st ed., Penguin Books, 2013.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. "Napoleon I." Encyclopaedia Britannica, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/biography/Napoleon-I.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. "French Revolutionary Wars." Encyclopaedia Britannica, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/event/French-revolutionary-wars.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. "November Insurrection." Encyclopaedia Britannica, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/event/November-Insurrection.

Thompson, Martyn P. “Ideas of Europe during the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars.” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 55, no. 1, 1994, pp. 37–58. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709952.

Wilson, Andrew. The Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation. 4th ed., Yale University Press, 2015.

Yekelchyk, Serhy. Ukraine: What Everyone Needs To Know. 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 2020.