The 30 Years' War: How Modern Europe Was Formed

The Thirty Years' War remains one of Europe's longest-lasting and deadliest conflicts in history. Beginning in the early 17th century, the Thirty Years' War originated from the religious turmoil that resulted from the Protestant Reformation, which occurred just over 100 years prior in 1517. However, the religious nature and factionalism that defined the early stages of the conflict did not last. Towards the end of the conflict, it was clear to everyone involved that the war had evolved past religious differences and instead took on a much more secular and political nature. The war was no longer about God or faith but rather power and influence. What began as a small and regional conflict in the Holy Roman Empire quickly spiraled out of control and would engulf all of Europe in three decades of unprecedented levels of death and destruction that would ultimately claim the lives of millions.

Ferdinand II: King Of Bohemia

In 1619, Ferdinand II, the King of Bohemia, ascended to the throne of the Holy Roman Empire. The situation in the Holy Roman Empire was already tense; Catholics and Protestants were at one another's throats as there had been a flair-up of sectarian violence only a few years before. The last century was marked by a series of bloody wars fought between the two Christian factions, which brought about a deep divide in the empire. An uneasy truce was finally reached in 1555 with the Peace of Augsburg. This document promised religious tolerance throughout the empire and allowed its citizens and princes to choose their faiths how they pleased. Ferdinand II, however, was a devout Catholic and was staunchly opposed to the treaty well before he became emperor.

Once emperor, Ferdinand II disregarded the treaty entirely and forced his subjects to follow Catholicism and refused to recognize the legitimacy of any other opposing church. The Protestant rulers of Austria and the Czech Republic refused to adhere to this new decree. When imperial representatives were sent to Prague Castle to enforce this decision, they were thrown out of a high window in an event now referred to as the Second Defenestration of Prague. Now, in open rebellion, the Protestant princes and kings of the Holy Roman Empire mustered their armies and marched against Ferdinand II. Sweden and Denmark-Norway joined the war on the side of the rebel monarchs, and this started a cascade effect that dragged almost all of Europe into the conflict.

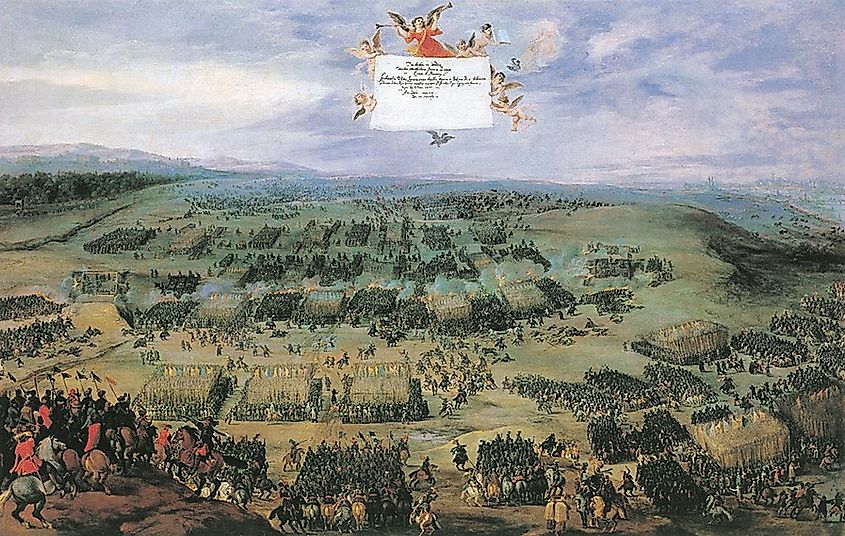

Bohemian Revolt

Much of Bohemia and the northern states of the Holy Roman Empire were now at war with Catholic factions within who supported the emperor. In an attempt to overthrow the Catholic Emperor Ferdinand II, the Protestants championed the Protestant prince Frederick V as his replacement. Frederick V enthusiastically accepted his chance to become emperor. But his attempt at the imperial throne would be short-lived. In 1620, the Bohemian army was soundly defeated at the Battle of White Mountain. With the revolt now in shambles, Catholic forces marched into Prague and crushed any remaining resistance. Even though the initial threat was over, Ferdinand II was now faced with an invasion on his northern border from Denmark-Norway. Spain was now supporting his armies, and the Netherlands had entered on the side of Denmark. The war was far from over.

Denmark Enters The Picture

Led by King Christian IV, Protestant Denmark was reluctant to join the war in its early stages. The Nordic kingdom relied heavily on trade with the Protestant majority states within Northern Germany and felt as though Ferdinand II would threaten them. However, upon hearing that the rival nation of Sweden was planning on entering the war on the side of the Protestants, Christian IV felt his hand was forced. He could not risk another monarch snatching away the prestigious and honorable title of being the defender of the Protestant faith.

The Danish army, now backed by England, pushed into the Holy Roman Empire. Small-scale success was found by the Danes early on, but it would not last. Christian IV clashed with the Count of Tilly, a loyal of Ferdinand II, at the Battle of Lutter in 1628 and was soundly defeated.

Later that year, Christian IV had no other choice but to plead with the Swedish king Gustavus Adolphus for assistance. Help was given but it was too little, too late. Christian's image was ruined amongst the Protestant nations, and he was forced to sue for peace in 1629. The treaty eased his financial concerns in Northern Germany in exchange for a guarantee that he would not reenter the war. Denmark's involvement in the conflict was essentially over.

The Warrior King Gustavus Adolphus

Despite being a nation of only a few million people, Sweden was able to field one of the most impressive militaries of the time. Its force only numbered around 20,000 soldiers, but what it lacked in manpower, it made up for in leadership, training, and discipline. The Swedish monarch, Gustavus Adolphus, was nothing short of a military genius and spent much of his rule drilling his new army and spending large amounts of his nation's treasury on outfitting them with the best weapons and armor available.

His troops were incredibly flexible and could fill different roles on the battlefield. For instance, if the cavalry suffered heavy losses, they could be replaced with infantry members and vice versa. The firing drills used by his musketeers also revolutionized European warfare. The tactic of mass, rank-by-rank, volley fire was invented by Adolphus and had a devastating effect on the enemy.

Adolphus met the Count of Tilly at the Battle of Battle of Breitenfeld in 1631 and won a clear victory. The Swedish king was victorious again the next year against the Count at the Battle of Rain in 1632, and Tilly later died from the wounds he sustained during the fighting. But despite Adolphus's clear mind for military matters, he was not invincible.

Adolphus was killed in action at the Battle of Lutzen in November 1632. His troops could still win the battle but were now disadvantaged. His army could claim a few more victories until they were finally defeated at the Battle of Nordlingen in September 1634. This battle would effectively mark the end of Sweden's push into the Holy Roman Empire for the next eight years.

France Tips The Scales

France had not so subtly been supporting the Protestant forces since the beginning of the conflict. Despite being a nation of devout Catholics, it was eager to see its neighbor weaken. A long rival of the Holy Roman Empire, France finally declared war in 1635 and came to Sweden's aid. France also declared war on Spain, which they felt was becoming too powerful.

The French forces made little gains in the territory of the Holy Roman Empire and spent most of their time fighting off a Spanish invasion from the south that eventually threatened Paris itself. In 1637, Ferdinand II died and was seceded by his son Ferdinand III. The new emperor was not equipped with the experience necessary to bring an end to the already excruciatingly long conflict. It is largely agreed that peace could have been reached much sooner if Ferdinand II had just lived a few years longer. Sadly, another ten years would be needed to bring peace. Despite experiencing success in France, the Spanish had to withdraw back to their homeland to deal with a Portuguese revolt in 1640. The fighting reached a stalemate for a few years until it was reignited by Sweden, which once again launched another invasion.

The End Of The War

The French and Swedish alliance was finally able to make considerable gains in the Holy Roman Empire. As the French pushed in the West, the Swedish were able to lay siege on the imperial capital of Vienna in 1645 but failed to take the city. In 1648, the Swedes captured Prague Castle, the site where the war had started nearly thirty years beforehand. With only a few areas in the empire under their control, the Holy Roman Emperor was forced to the negotiating table. The Thirty Years' War was finally drawn to a close with the signing of the Peace of Westphalia, a series of complex treaties and agreements that largely benefited the Swedish and French sides.

Sweden was granted control of Pomerania in Northern Germany. By controlling this land, it gave them total dominance over the Baltic Sea. The French were gifted the German-speaking lands of Alsace. Spain was forced to give up Portugal and any claims over the Netherlands. The Swiss Confederation was also officially recognized.

Religious tolerance was once again established in the Holy Roman Empire. Although there would be occasional flair-ups moving forward, religious violence between Protestants and Catholics never again reached the same levels as it did during the war. Religious institutions such as the Catholic Church also lost significant power over the affairs of monarchs across the continent regardless of their religious affiliation.

Wholesale Destruction And Devastation

The Thirty Years' War was one of the most brutal and chaotic periods in European history. It is estimated that as many as 8 million people died as a result of the war, most of whom were innocent civilians. During the conflict, armies on both sides struggled to amply supply or pay their troops, which forced them to loot nearly villages and towns for resources. Hundreds of settlements were destroyed throughout the war regardless of which faction the citizens supported. It was not uncommon for Protestant and Catholic armies to loot and sack cities and villages that were friendly to their cause. Sometimes, these rampages were done out of desperation, but in other cases, they were spurred on out of sheer greed and malicious intent.

Starvation and disease racked the civilian populations of the Holy Roman Empire. As marauding armies made their way through the land, they often left little but a few smoldering ruins in their wake. Even if food was found, it was often of poor quality and unsafe to eat. In total, it is thought that as much as 80% of all deaths were civilians rather than soldiers dying in battle.

Legacy and Conclusion

The aftermath of the Thirty Years War left Europe a changed place. The Holy Roman Empire was now in decline and would slowly begin to give up power to the emerging German kingdom of Brandenburg-Prussia. Spain also lost large portions of its holdings in the Netherlands and would no longer rule over Portugal. The Spanish Empire was still going strong, but it would never again hold the same level of power with European geopolitics again.

Clear borders now drawn around ethnicity and religion would become the norm and eventually laid the groundwork for the beginnings of the modern nation-states that we see today. Even though the Thirty Years' War is often overlooked or thought of as a regional conflict, it had a tremendous impact on forming the modern Europe that we see today.