The Habsburg Empire: and the Ukrainian National Identity

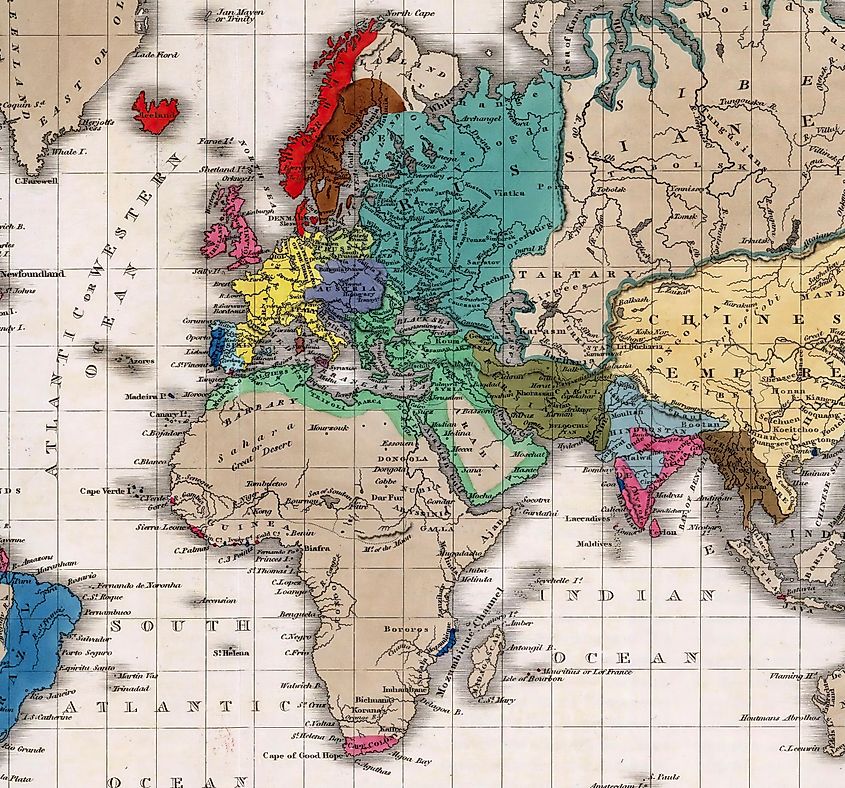

The Habsburg line stands as a major component in Europe's royal lineage. Their sway has been felt from the Middle Ages right through to the onset of the 20th century. It was a vast, multi-ethnic domain known for its influential role in Europe’s politics. Across multiple centuries, the Habsburgs broadened their control through marriage alliances and territorial victories. The empire's peak was during the reigns of Charles V and Rudolf II in the 16th and 17th centuries, spreading across distinctive territories and ethnic diversities.

Within these extensive boundaries, a unique identity formed among the Ruthenians, also known as Ukrainians, who underwent an evolution reflecting their specific cultural identity throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Some of them inclined towards a sense of shared Slavic identity with Russia, emphasizing common linguistic, religious, and cultural ties. At the same time, other Ruthenians increasingly embraced a distinct national identity. Influenced by cultural developments and exposure to nationalist movements in Europe, this group wanted to emphasize the unique history of the Ukrainian people.

The emergence of a specifically Ukrainian national consciousness marked a departure from the broader Slavic identity and set the stage for a distinct Ukrainian nationalism. This divergence among the Ruthenians reflected the complexities inside the Habsburg Empire. Looking at their identity inside the Habsburg Empire before the nation of Ukraine existed is an important step in understanding the current nationalistic views of the Ukrainian people.

The Ruthenians

Before talking about the Habsburg Empire, knowing who exactly “Ruthenians” are is important. In many articles and books, the terms Ruthenian/Ukrainian are used interchangeably when speaking about this time frame. It is also important to know the context of the term.

How words change and organically change over time is an interesting part of any language. At first, the Latin name of “Rutheni” was meant for a Celtic tribe in Gaul. By the Middle Ages, it became to be associated with the people of Rus, particularly in the context of the Kingdom of Hungary and later in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. So, over time, that name was given to people in the area of Kyivan Rus.

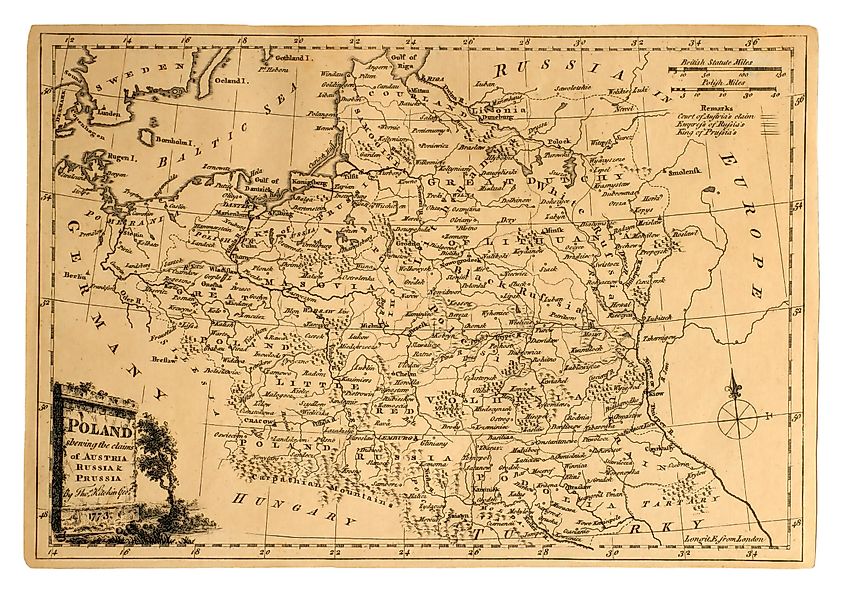

In the 16th century, the term Ruthenian became linked to Ukrainians and Belarusians within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, distinguishing them from Muscovites, later called Russians. After Poland was divided in the period from 1772 to 1795, the term Ruthenian started being more distinctly associated with Ukrainians living under Habsburg dominion in regions like Galicia, Bukovyna, and Transcarpathia.

Under Habsburg rule, the term Ruthenian denoted a linguistic and cultural identity and had some political implications. It became a marker for those Ukrainians living within the Habsburg Empire's domains, emphasizing their distinctiveness in contrast to other groups. Even though they shared a cultural background and lived in the same greater region, Ukrainians in the Russian lands were not commonly called Ruthenians. In essence, the term Ruthenian witnessed an evolution, from its origins in Gaul, it became a label intertwined with the identity of Ukrainians and Belarusians, particularly under various European powers and empires.

Partition of Poland

During the closing decades of the 18th century, a sequence of divisions struck Poland and significantly transformed Europe's map. In layman’s terms, Poland was falling apart at the seams after years of conflict and a dysfunctional political system. It did not help that the expanding ambitions of neighboring powers—Russia, Prussia, and Austria—played a crucial role.

The initial domino to fall into a series of catastrophic divisions was The War of the Bar Confederation. This internal revolt was against King Stanisław August Poniatowski and his pro-Russian stance. Russia intervened to suppress the rebellion, and the First Partition of Poland in 1772 followed, with Russia, Prussia, and Austria annexing Polish territories. The partitioning powers sought to suppress the rising tide of nationalism and liberal movements within Poland, which were seen as threats to the autocratic and feudal structures of the neighboring empires.

The Habsburg Empire, in this case Austria, gained control over Galicia, which had a significant Ruthenian population. They already controlled Transcarpathia, and in 1774 they annexed Bukovina from Moldova. All of Galicia, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia, regions within the Habsburg Empire, had significant Ruthenian populations. Subsequent partitions in 1793 and 1795 further disintegrated Poland, with Russia, Prussia, and Austria annexing additional territories. The most important part of the partitions in the context of Ukraine and Russia is how lands of Ruthenian/Ukrainians remained in separate empires. Any sort of nation-building remained difficult when the people were scattered all over different European empires.

Poles and Ruthenians During the Napoleonic Wars

Under the Habsburg Empire, the relationship between the Poles and Ukrainians was a crucial feature of Galician life. The Poles made up the majority of citizens in the west, while the majority of the east were made up of Ruthenians. Despite this, Poles made up the majority of the elite class, causing a clear power divide. The educated Ruthenians were mostly members of the clergy. The majority of the rest of the Ruthenians were peasants without any control in the political sphere of the Habsburg Empire.

This divide between Poles and Ukraine became apparent during the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon, seeking allies in Eastern Europe against his enemies, made promises to restore Poland. As a result, many Poles joined the French military. Polish legions and troops fought under the French flag, hoping for the recreation of an independent Poland.

On the other hand, the Ruthenians had a varied response to Napoleon and France. Some Ruthenians saw Napoleon as a potential liberator from foreign rule or as a force for political change. Others opposed him due to concerns about the disruption caused by war or ideological differences. Serhii Plokhy, author of The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine, explained that Ivan Kotliarevsky, one of the founders of Ukrainian literature, formed a Cossack detachment to fight Napoleon.

According to the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, some prominent Ukrainians, like Archbishop Varlaam Shyshatsky, openly endorsed Napoleon's invasion. During Napoleon's disastrous winter retreat from Russia, Ukrainian troops effectively blocked efforts to invade the provinces of Left-Bank Ukraine from Belarus. The Ukrainian gentry, apprehensive about Napoleon's Polish ambitions, ultimately remained loyal to Russia.

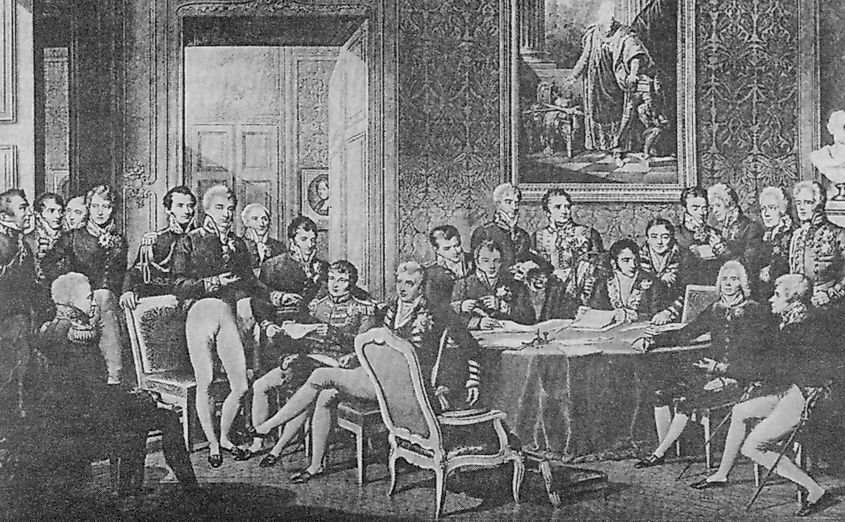

In essence, the stance of Ruthenians/Ukrainians towards Napoleon was diverse, reflecting the complex landscape of the time. While the Congress of Vienna in 1815 reorganized Europe after the Napoleonic Wars, the Ruthenian-dense areas of the Habsburgs remained under their control.

Polish Rebellions

While talking about Russia and Ukraine, it might seem off-topic to detour and talk about Poland. In fact, the insurgencies of Poles in the 1800s had a collateral influence on the Ukraine-Russia relationship.

When the Napoleonic Wars reached their conclusion, and Europe's rulers convened to restore stability via the Congress of Vienna in 1815, many questions remained unresolved. The question about what to do with Poland was among those with significant weight. They decided to establish the Kingdom of Poland and put it into a union with the Russian Empire. The Tsar of Russia would serve as the King of Poland, but he promised them their constitution and army and that they would be autonomous.

15 years later, there was widespread sentiment in Poland that these promises had been violated, and a small mutiny turned into something much larger. The revolt of 1830, also known as the November Uprising, started when Polish cadets tried to kill their Russian commander. Targeting the commander was a highly symbolic act. It represented a direct challenge to Russian authority and control over the Polish armed forces and, by extension, over Poland itself.

Others saw the defiant act, and the uprising quickly spread to other parts of Poland. In response to this growing movement, the Polish Diet proclaimed Poland's independence from Russia and dispatched envoys to assert claims over territories they deemed rightfully Polish. However, the Russian perspective was different. They viewed the region as an integral part of their nation, a vision of Slavic unity. Unwilling to compromise on this stance, the Russians refused to engage in negotiations.

Prussia and Austria adopted a hostile stance toward the Polish Revolution. The success of Poland in its conflict with Russia posed a threat to the status quo of Polish territories under Prussian and Austrian control, and they were worried it could fuel revolutionary movements in their nations. Both aided the Russian effort in case it spilled over into their borders.

The insurrection dealt considerable damage to the Russian troops, yet despite the revolt's efforts, it was crushed by Russia's armed forces. The quelling of this rebellion sparked joy within Russia and heightened a sense of national honor. Meanwhile, across Europe, where the winds of nationalism were stirring, there was a wave of sympathy for the Polish cause.

It also wasn’t the last Polish uprising. 18 years, it started again. This time there were significant rebellions on the Austria-Hungary side too. The 1848 Polish revolt was part of the Springtime of Nations, a series of revolutions throughout Europe. Within territories ruled by the Habsburgs, the uprisings particularly took place in Galicia, now part of present-day Ukraine and Poland.

The Poles wanted greater autonomy and the restoration of the Polish state. Civil rights and the eradication of serfdom were two of their demands. From the moment Poland was segmented and shared between the Russian Empire, Austrian Empire, and Kingdom of Prussia, Poles never let go of their desire for national independence. During this uprising, we start to see the rise of Ruthenian power and Ukrainian identity inside the Habsburg Empire. When the Poles rebelled, the Austrian governor at the time wanted the support of loyal Ruthenians as a counterbalance.

Ruthenian bishops were allowed to form the Supreme Ruthenian Council, the start of a distinctively Ukrainian organization in the Habsburg Empire. If we contrast that with Ukrainians in Russia, Austria had more freedoms available. In Russia at the same time, Ukrainians were not allowed to form or join groups promoting Ukrainian culture.

By late 1848, the Habsburg forces had suppressed the uprising in Galicia. The failure of the uprising led to a period of repression, but the demands for Polish autonomy and national identity remained an ongoing issue. Less than twenty years after their previous attempt, the Polish people rose in rebellion again, this time against Russian rule. This occurred during the January Uprising of 1863–1864.

Triggered by oppressive Russification policies, it began on January 22, led by Polish nobles and intellectuals. The insurgents aimed to restore national independence. Despite initial successes, the uprising faced a brutal Russian response. Lacking foreign support, the rebels struggled, and by 1864, Russian forces quelled the rebellion. The aftermath brought increased repression and Russification. The Russian Empire started to crack down on not only Polish cultural institutes but Ukrainian ones as well. The Russians undertook a wave of acts to solidify the ‘Russian’ nation. Soon after, all Ukrainian publications were banned, and the government even denied the Ukrainian language existed.

So while the Polish rebellions in the 19th century helped to raise the Ruthenian standing in the Habsburg Empire, in the Russian Empire, they helped led to greater censorship against Ukrainian culture.

Russophilism versus Ukrainophilism

Due to the 1848 revolution, the foundations of a new nation of people were beginning to form. The creation of the Supreme Ruthenian Council was the first step of this process. One problem was that the Ukrainian people were still divided. Certain people leaned towards favoring Poland, others demonstrated a preference for Russia, while some supported pro-Ukrainian sentiments.

By 1863, Ukrainians on both sides of the Austria-Hungry/Russia border were free. Serfdom had been eradicated in both empires. The Russian government, faced with a populace now empowered with the freedom of choice, wanted to steer these individuals towards embracing the idea of a unified Russian nation. They banned Ukrainian publications, a move that became permanent in 1870. In 1875, the Tsar prohibited Ukrainian publications from being brought into Russia and helped fund Galician newspapers fighting the Ukrainian language in Galicia. Tensions escalated when Alexander II issued the Ems Ukase, a decree prohibiting the import of Ukrainian books from abroad, and barred theater and art performances in the Ukrainian language.

On the other side of the border, in Galicia, freedom of thought was more accessible. Even still, two distinct groups were arising in the area; Russophiles and Ukrainophiles.

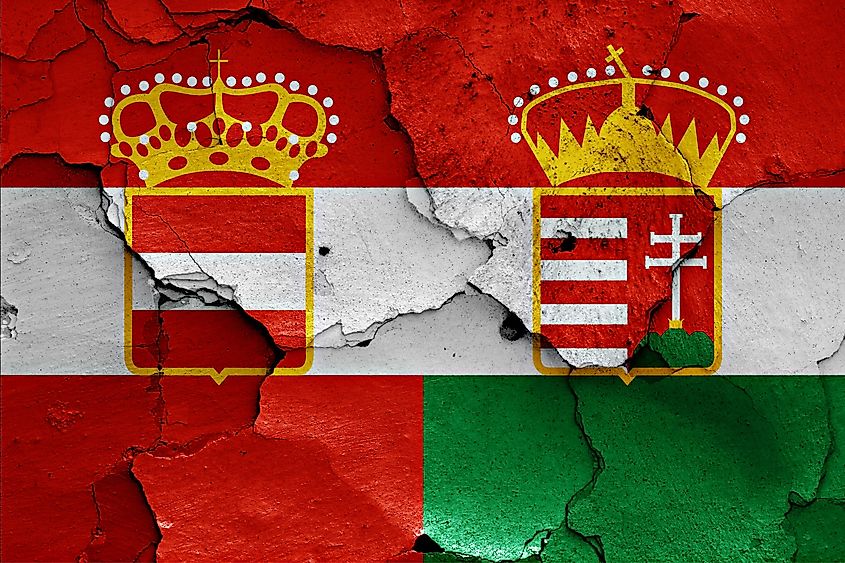

In 1876, the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, restructured the Austrian Empire into a dual monarchy of Austria and Hungary. It created a shared monarchy with a common ruler, Franz Joseph I, while allowing each region its parliament and government for domestic affairs, fostering a delicate balance. In Galicia, Poles, being the dominant ethnic group in the region, enjoyed a degree of autonomy and influence. However, the Ruthenians felt marginalized and underrepresented. This discrepancy fueled tensions between the two groups.

The sense of betrayal and marginalization felt by many Ukrainians led to increased support for the Russophile movement. This movement saw closer ties with Russia, or even incorporation into the Russian Empire, as a potential solution to their grievances. They felt betrayed the Poles gained more autonomy, but Ruthenians did not, so why would they support the Habsburgs after this? Towards the end of the 1860s, this initiative seized authority over numerous Ukrainian establishments. The conflict between Poland and Ukraine was consistently destined to play a role. Many of these Ruthenians saw the return to the greater Russia as a way to counteract Polish influence.

At the same time, in Russia, when people promoting the Ukrainian culture were being ostracized, in Galicia, it was being permitted. Many Ruthenians in Habsburg lands were starting to think they were part of a large nation or people. That bigger people was not a union with Russia but a union between the Ruthenians under Habsburg control and the Ukrainians in Russia. They were looking over at the Ukrainians on the Russian side as the missing piece of their nationality puzzle.

According to Andrew Wilson, by 1900, Ruthenians in Galicia had begun to call themselves and their brothers in Russia ‘Ukrainians.’ Ukrainophiles from Kyiv and Galician were working together to help promote this idea. They helped set up newspapers and distribute their ideas to the masses. Over time, the Ukrainophiles maintained momentum in the Habsburg regions. In 1893, Austrian authorities allowed the Ukrainian language in schools, a huge victory for the movement.

The movement was tied to socialism, which gained a lot of steam and won poor peasants' hearts. Russophiles on the other hand were associated with conservatist regimes. The 1907 Vienna parliament elections showed how far the two sides were headed, according to Paul R. Magocsi, in his book A History of Ukraine. The Russophiles only captured 5 seats while the Ukrainophile candidates captured 22.

The relationship between Poles and Ukrainians remained tense, and the ethnic conflict intensified with peasant strikes against Polish landlords and student clashes. Reforms, including universal suffrage, increased Ukrainian representation, but a Ukrainian-Polish compromise failed due to opposition, maintaining the old electoral system. Despite this, by 1914, Ukrainophiles made some real inbounds, including plans to make a Ukrainian university, their own board of education, and more.

All this progress they had made inside the Habsburg Empire came crashing down as the Great War engulfed Europe in a war to end all wars.

Key Takeaways

The Habsburg Empire played a significant role in shaping Eastern Europe's history and national identity. Ever since they came to power around the 13th century, they ruled over diverse ethnicities and people. How they ruled varied greatly compared to their neighbors, the Russian Empire. As well, how the Habsburgs ruled influenced the development of Ukrainian identity, in the middle of both uprisings and rebellions.

The emergence of distinct Ukrainian nationalism, driven by factors like Russophilia and a desire for autonomy, underscores that around this time Ruthenians/Ukrainians started to see their culture as a distinct nation. There was a conflict in the minds of this new movement. Did their alignment lean towards pro-Russian sentiment, or were they creating a unique perspective? Inhabiting territories governed by both the Habsburgs and Russians show a narrative where 19th-century conflict still echoes in the contemporary Ukraine-Russia relationship.

Works Cited:

Leslie, R. F. “Polish Political Divisions and the Struggle for Power at the Beginning of the Insurrection of November 1830.” The Slavonic and East European Review, vol. 31, no. 76, 1952, pp. 113–32. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4204407.

Lewak, Adam. “The Polish Rising of 1830.” The Slavonic and East European Review, vol. 9, no. 26, 1930, pp. 350–60. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4202527.

Magocsi, Paul R. A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples. 2nd ed., University of Toronto Press, 2010.Magocsi

Reid, Anna . Borderland : A Journey Through the History of Ukraine. 2nd ed., Basic Books: Member of The Perseus Book Group, 2014.

Plokhy, Serhii. The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine. 2nd ed., Basic Books, 2022.

Plokhy, Serhii. Lost Kingdom: The Question For Empire and the Making of the Russian Nation. 1st ed., Basic Books, 2017.

Rapport, Mike. The Napoleonic Wars: A Very Short Introduction. 1st ed., Oxford University Press, 2013.

Roberts, Andrew. Napoleon the Great. 1st ed., Penguin Books, 2013.

Schlögel, Karl. Ukraine: A Nation On The Borderland. Translated by Gerrit Jackson, 2nd ed., Reaktion Books, 2022.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. "January Insurrection." Encyclopaedia Britannica, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/event/January-Insurrection.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. "Western Ukraine Under the Habsburg Monarchy." Encyclopaedia Britannica, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/place/Ukraine/Western-Ukraine-under-the-Habsburg-monarchy.

Wilson, Andrew. The Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation. 4th ed., Yale University Press, 2015.

Yekelchyk, Serhy. Ukraine: What Everyone Needs To Know. 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 2020.