The Great Stink of London

By the mid-19th century, London, the capital of the vast British Empire, was a city bursting at the seams. Its population had exploded, surging from just over a million in 1800 to nearly three million by 1850. With this rapid growth came significant challenges, particularly in public health and urban sanitation. The River Thames, London’s lifeblood, had become an open sewer. Untreated human waste, industrial byproducts, and slaughterhouse refuse poured into the river daily. Yet despite its importance as a source of drinking water, the Thames became a putrid cesspool.

This dire situation reached its peak in the summer of 1858 when a combination of sweltering heat and decaying organic material unleashed an overpowering stench that permeated the city. Known as "The Great Stink," this crisis brought London to a standstill. The stench infiltrated Parliament, interrupted commerce, and fueled public outrage, compelling political leaders, engineers, and health advocates to act decisively.

But in reality, the Great Stink was much more than a temporary inconvenience: it was to be a catalyst for transformative change. It exposed the inadequacies of London’s sanitation system and ignited a movement that reshaped public health and urban engineering. By addressing the crisis effectively, London ended up setting a new standard for modern cities, paving the way for comprehensive sewer systems and public health reforms across the globe.

A River of Filth: The Conditions Before 1858

Before 1858, London’s sanitation was dangerously inadequate. The lack of a centralized sewer system meant that waste was disposed of in cesspits or dumped directly into the Thames. These cesspits often overflowed, contaminating both streets and water supplies, and by the early 19th century, the river had become a de facto sewer, filled with raw sewage and industrial runoff.

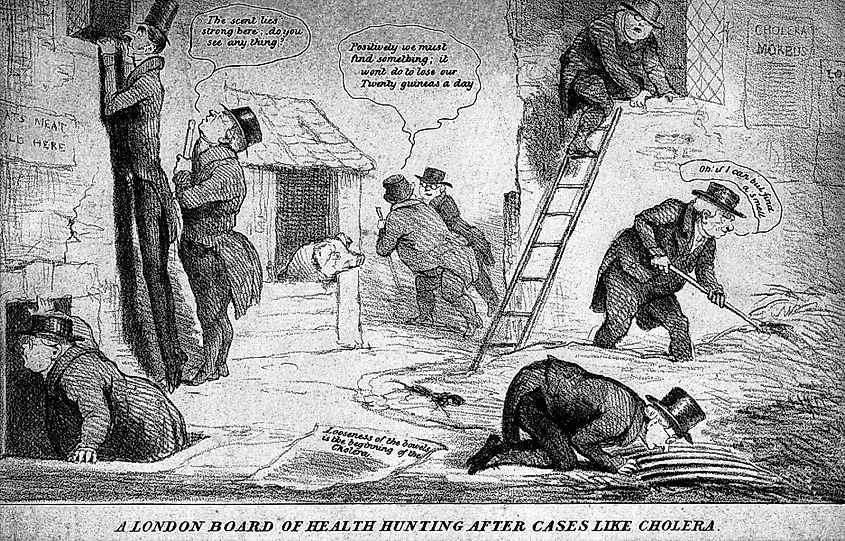

The health implications were devastating. Cholera, once unknown in Britain, became a recurring nightmare. The first major outbreak in 1832 killed over 6,000 Londoners, followed by even deadlier epidemics in 1849 and 1854. These outbreaks underscored the link between contaminated water and disease, though the prevailing "miasma theory" blamed foul air rather than waterborne pathogens. The Thames, however, was undeniably a breeding ground for illness.

Public complaints about the state of the river were nothing new but had largely been ignored. The city’s leadership, hindered by political inertia and a lack of consensus, failed to implement meaningful change, and by 1858, the situation had become untenable, setting the stage for one of the most infamous crises in London’s history.

The Great Stink and a Summer of Crisis

The summer of 1858 was one of the hottest on record. As temperatures soared in July, the waste in the Thames began to ferment, releasing noxious gases that blanketed the city. The stench was so overpowering that residents fled riverside neighborhoods, and businesses suffered as customers avoided the area.

The crisis reached Westminster, where members of Parliament struggled to conduct business despite the foul odor. Records describe members soaking curtains in lime chloride and draping them over windows in a futile attempt to mask the smell. Benjamin Disraeli, the Chancellor of the Exchequer and later the Prime Minister, famously described the Thames as a "Stygian pool," referencing the mythological river of the underworld.

The public outcry was immediate and deafening. Newspapers lambasted the government for its inaction, and citizens demanded solutions. The crisis was not only a public health emergency, but it also became a political one, forcing Parliament, under immense pressure, to allocate funds for a long-overdue overhaul of London’s sanitation infrastructure.

Joseph Bazalgette and the Birth of Modern Sanitation

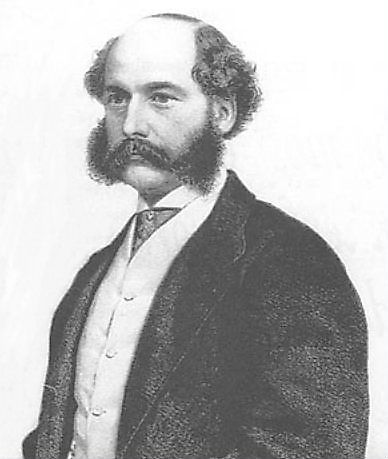

Joseph Bazalgette, a visionary civil engineer and chief of the Metropolitan Board of Works, was at the heart of the solution. Tasked with designing a comprehensive sewer system, Bazalgette proposed a bold plan to intercept waste before it reached the Thames and divert it downstream to treatment facilities.

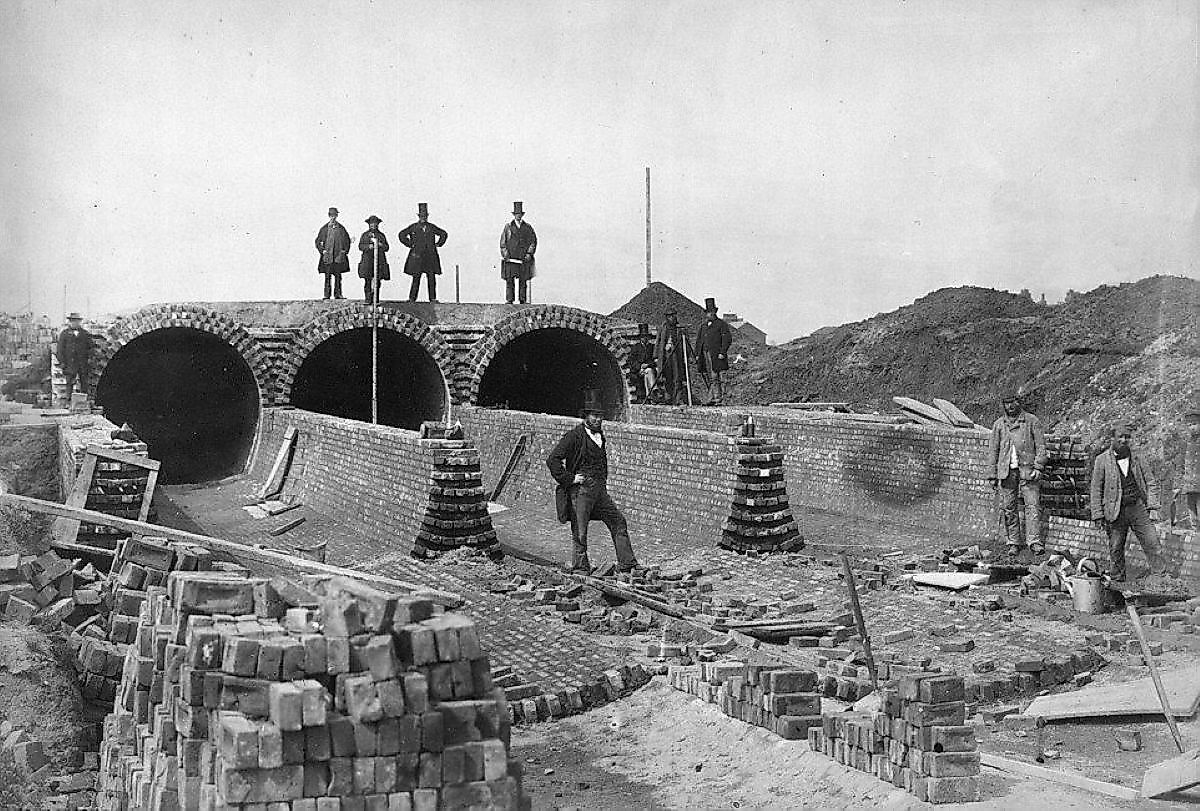

Construction began in 1859, with over 82 miles of sewers and 1,100 miles of street drains under Bazalgette’s supervision. His design included massive brick-lined tunnels capable of handling waste from a growing population. Key components of the system included the Crossness and Abbey Mills pumping stations, which used steam engines to move waste to outflow points east of the city.

Bazalgette’s attention to detail was extraordinary. He insisted on using durable Portland cement and over-engineered the sewers to accommodate future population growth. His work was so thorough and effective that it alleviated the immediate crisis and set a global standard for urban sanitation.

Political and Public Health Reforms

The Great Stink also spurred significant political and public health reforms. Prime Minister Lord Palmerston and public health advocate Edwin Chadwick played pivotal roles in driving change. Chadwick, whose earlier work on sanitation had influenced the Public Health Act of 1848, used the crisis to push for stricter regulations.

Although the 1848 act had limited success, the events of 1858 paved the way for the Public Health Act of 1875. This legislation established clear responsibilities for waste management and sanitation, ensuring that local authorities maintained modern infrastructure.

The Great Stink marked a turning point in how governments approached public health. No longer seen as an individual responsibility, sanitation became a civic priority, funded and maintained by public resources.

The Lingering Legacy of the Great Stink

The Great Stink certainly left a lasting legacy. Bazalgette’s sewer system, completed in 1865, drastically reduced cholera outbreaks and other waterborne diseases. The system’s durability has stood the test of time, with much of it still in use today.

Beyond its immediate impact, the Great Stink also greatly influenced urban planning worldwide. Cities from Paris to New York adopted similar sewer systems, recognizing the importance of sanitation for public health and quality of life. Bazalgette himself is remembered as a pioneer, with memorials and plaques commemorating his contributions dotted across London.

The easiest to find if you’re traveling to the city is located near Hungerford Bridge and the Golden Jubilee Bridges, near the Victoria Embankment promenade. Unveiled in 1901, it features a bronze bust of Bazalgette set within a decorative stone façade with the Latin inscription "Flumini Vincula Posuit," meaning "He put the river in chains." This is a fitting tribute indeed to Bazalgette's role in ensuring London never again suffered such a horrendous experience.

Visiting London's Victorian-era Engineering Marvel

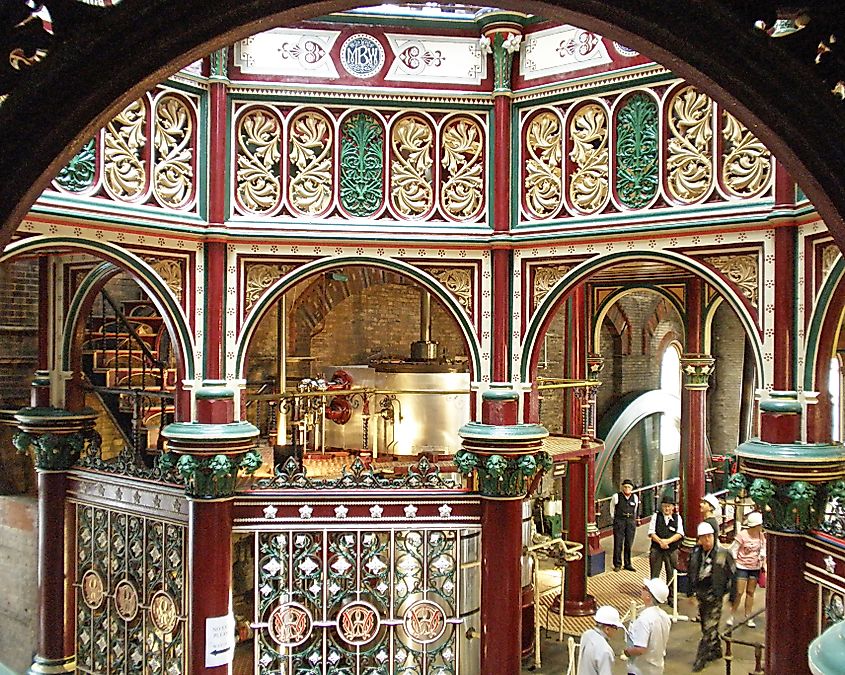

Travelers to London can also get an up-close look at the engineering feats that transformed the city with a visit to the Crossness Pumping Station. Built-in 1865 as part of Bazalgette’s revolutionary sewer system, Crossness was instrumental in diverting sewage from central London, dramatically improving public health.

Located in Abbey Wood, southeast London, and accessible from the city center by the Underground (or “Tube”), the pumping station is now a heritage site and museum. Dubbed the "Cathedral on the Marsh" for its impressive size and its vividly painted columns and arches, its intricate cast-iron interior has been restored to its original grandeur. You’ll also see the original preserved beam engines, including the Prince Consort engine. Guided tours are available and offer unique insights into the station’s role in Bazalgette’s visionary plan, highlighting how the system curbed cholera outbreaks and eliminated the Great Stink of 1858.

You can also explore the larger network of Victorian-era sewers through tours that provide access to parts of the underground infrastructure, revealing the brick-lined tunnels that have served London for over 150 years. Run by Thames Water, the company responsible for maintaining and operating the system, tours include a visit to Abbey Mills Pumping Station, protective clothing (including overalls, gloves, waders, and a hard hat), a chat about London sewer development, and a walk through the sewer.

The Final Word

The Great Stink of 1858 was to be much more than an unpleasant episode in London’s history. In fact, it was to prove itself a transformative moment that redefined urban living not just in England but worldwide. Faced with an unprecedented-scale crisis, the city responded with innovation, collaboration, and a commitment to public welfare.

Joseph Bazalgette’s sewer system, now regarded as one of the wonders of the industrial age, and the reforms it inspired continue to protect Londoners over 150 years later. His response to the Great Stink is a testament to the power of foresight and determination to overcome even the most daunting challenges. As modern cities confront new environmental crises, the lessons of 1858 remain as relevant as ever.