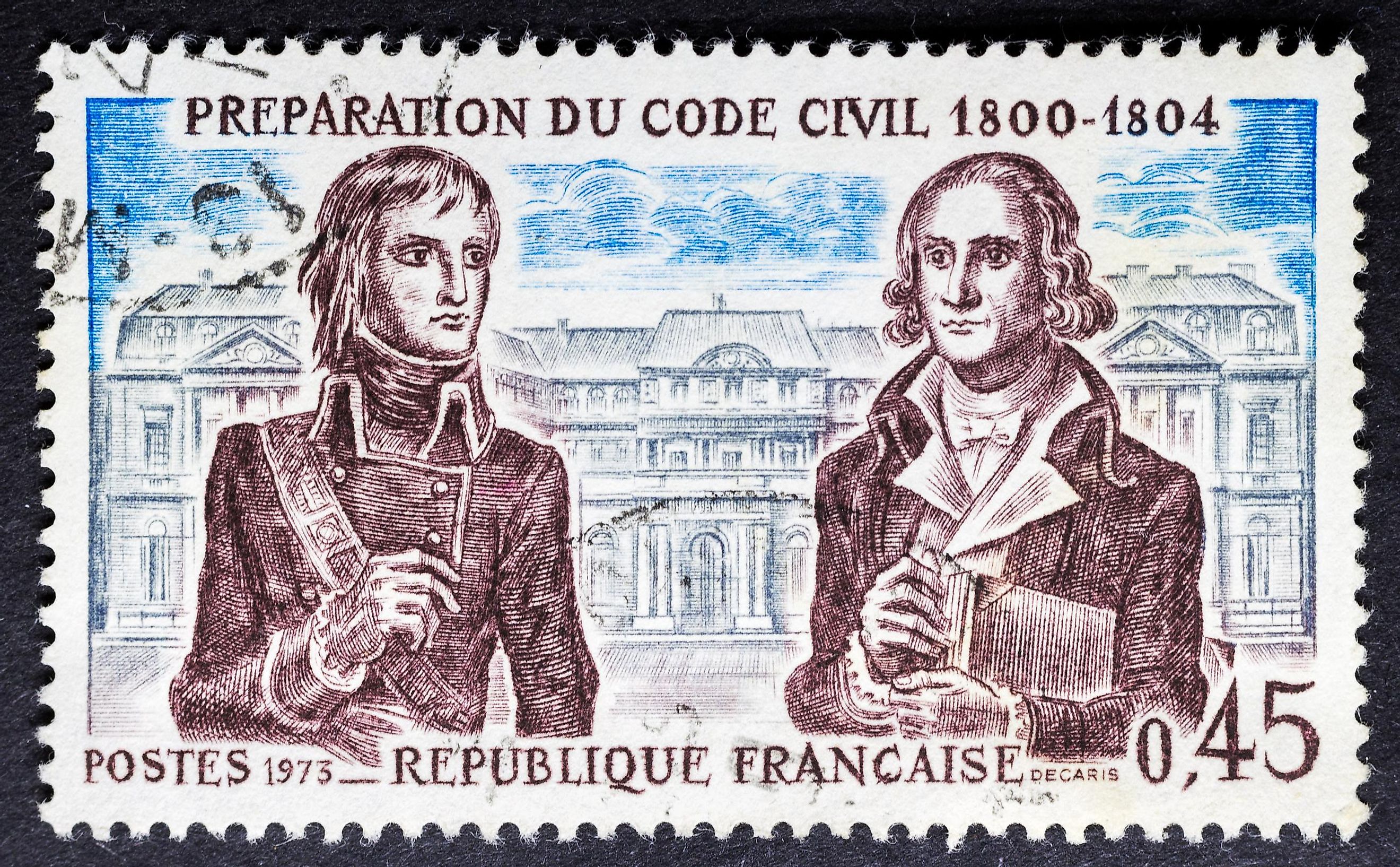

The Napoleonic Code

A revolution without codified reforms is nothing more than a forum of aimless protest. The Napoleonic Code was a 6-hundred-page masterpiece and Napoleon Bonaparte's early attempt to unify France's chaotic legal system. The French Revolution overthrew the feudal monarchy a decade prior, leaving the country in disarray. Centuries-old code differed from village to village, resulting in endless bickering and frustration for average citizens. Miraculously, the Napoleonic Code continued after the restoration of the French monarchy. Even though Napoleon was permanently imprisoned in 1815, the King’s charter preserved many elements of the Napoleonic Code. Moreover, the Napoleonic Code restructured how citizens worldwide valued their right to liberty, and that momentum has continued today.

Background

Spawning a new civil code is no mean feat. Napoleon’s code came from a unique circumstance, in which he had amassed ultimate power, and the preexisting structures were dysfunctional. The French historian and philosopher Voltaire famously decried his fragmented country, where “when you travel in this kingdom, you change legal systems as often as you change horses.” Indeed, laws in the southern regions of France were based on old Roman statutes, and northern decrees were even more varied. Therefore, a change would be necessary.

In order to establish a legal system, Napoleon needed a foundation that the general population could agree on. After stripping the former monarchy of its influence, the First French Republic provided the perfect source of values and legal directions to take inspiration from. Furthermore, the power needed to institute this code had to be absolute; from 1799 to 1804, Napoleon performed a “coup within a coup” to gain that authority, establishing himself as Emperor shortly after introducing the code. A more significant issue was maintaining that authority, given France was constantly invaded by external powers eager to reinstitute the former monarch. In his final defeat and exile in 1815, Napoleon stated that “My glory is not that I won forty battles and dictated the law to kings… Waterloo wipes out the memory of all my victories… But what will be wiped out by nothing and will live forever is my Civil Code.”

The Code

Effective March 21st, 1804, the Code was gladly received across France. Standardization was direly needed, and the scattered ideals of the Revolution finally had a place to linger. Napoleon was influenced by his revolutionist peers; however, his bias and subjective opinion leaked into specific segments of the new laws. In a grossly conservative move, he reinstated slavery in 1802, and the code established in 1804 failed to correct that injustice. This act caused more than 300,000 people to suffer until France managed to re-abolish slavery in 1848. Therefore, modern opinion hesitates to join in on celebrating the glories of Napoleon’s problematic conduct. Notably, the Code was not the first to establish a civil-law legal system in Europe, but it was the first to affect distant colonies. One appeal of the code was that it worked to dismember feudal systems, which many regions in France needlessly maintained.

Property

The code is a database used to settle disputes. Before this standardization, France's economy struggled without universal laws to regulate sales or loans. Napoleon devoted a significant section of the Code to these issues. A distinction was made between moveable and immovable assets, which are precisely what they sound like: a necklace is a moveable property, and a house is an immovable property. The Code establishes different terms for using moveable and immovable properties as security for a debt. Mortgages, gambling, sales, auctions, and repurchases are also addressed, and reasonable conduct for either party to abide by is established. Furthermore, the laws clarify that if you are not a guardian of a property, an administrator, forbidden by the government, or married to the other party, then you are allowed to buy or sell.

Family and Individual Rights

Napoleon recognized the need to codify and resolve property disputes following divorce. The Code discusses regulations for the causes of divorce and the respective rights of married persons as ‘active’ or ‘passive’ members of the community. Ultimately, husbands were granted ludicrous powers over wives, who ended up losing even more rights due to the code. Children also played a critical role, due to the volatile nature of inheritance disputes. Napoleon’s code is famously unfair to illegitimate children, who are not granted many protections. Heirs, naturally, are conferred significant protection and security by the code, which may have been an attempt to bolster early concepts of a “nuclear family.” Fascinatingly, emancipation and guardianship are also covered in the Code.

Lasting Influence

It was not perfect, but it was widespread. The code made its way into French-controlled colonies overseas, enacting immediate changes. At least for white landowning men, some sense of equality was established that had not yet occurred throughout the feudal era. The momentum of the Civil Code, while not the first of its kind in Europe, continued over centuries because it was the first of its kind in foreign colonies. The Code's influence and the introduction of early individualism cannot be understated. A significant aspect of the code is that it also granted the right to religious dissent, meaning that secularism was now present around the world in a capacity that had never been seen.

Several countries were directly and indirectly impacted by the contents of the code. The Netherlands’ civil code of today is based on a document called the Burgerlihj Wetboek. The Burgerlihj Wetboek was an attempt to replicate the Napoleonic Code’s structure while improving the content. A 19th-century Greek civil code also followed Napoleon’s principles, while also being influenced by Roman Code and German Legal Theory. Last, Latin American countries were directly affected by the Napoleonic Code, and therefore it laid the groundwork for their constitutions upon achieving independence. Although many specific rules and regulations were removed or updated in each of these countries, scholars agree that the structure and philosophy have carried over until today.

Conclusion

Arguably, the Napoleonic Code was a rough draft. The perspective of only one, flawed, man is evident in it. Women remained second-class citizens, slavery was reinstituted, children born out of wedlock were neglected, and only white landowning men received the boon of true equality. However, the successors of France's governing body chiseled away at the Code until only the spirit of it remained in what we have today. However, the overall trajectory could not have been achieved if the original never existed. Love him or hate him, Napoleon changed the world with his paradigm-shifting code.