What Was Russia Like Before The Russian Revolution?

The Russian Revolution must be understood in its historical context. Indeed, limited industrialization, discontent amongst the urban workers, and an incompetent monarch contributed to revolutionary fervor in the decades before 1917. This, paired with the rise of Marxism in Europe and Russia, set the stage for several uprisings during the first two decades of the 20th century.

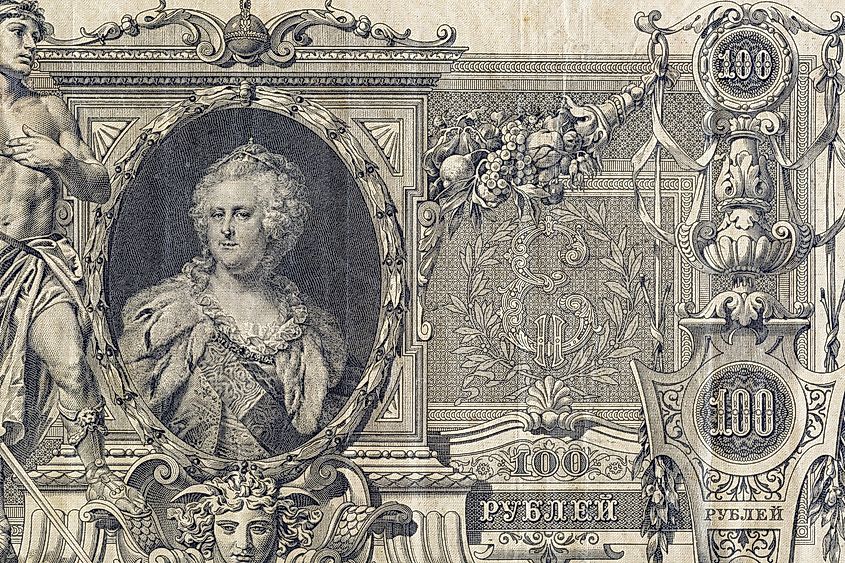

The Russian Empire

In the late 19th century, Russia was dealing with the consequences of being a multiethnic, multinational, multireligious, and largely feudal country. According to an 1897 census, out of the 120 million people in the Russian Empire, under half were ethnic Russians. The largest minorities were the Ukrainians, Poles, and Belarusians. They shared some sort of Slavic identity with the Russians and were also mostly Eastern Orthodox Christians. However, Central Asia had notable Kazakh, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, and Tajik minorities, most of whom were Muslim. The Caucasus, a mountainous region in southern Russia, also contained hundreds of different religious and ethnic groups. Western Russia saw notable German, Finnish, Lithuanian, and Estonian minorities, among others. Finally, Jews made up between four to five percent of the population. As the 19th century progressed, pogroms against Jews increased, with them often being used as scapegoats for the problems facing the Empire.

Perhaps the biggest problem in Russia in the late 19th century was its failure to modernize. While the major powers in Europe, like the United Kingdom (UK) and Germany, had transformed from agricultural to industrial economies, Russia was still a functionally feudal society. This was despite Czar Alexander II "liberating" the serfs in 1861, since the land was then given to a landlord and redistributed via the village commune. Thus, most peasants ended up with less and worse quality land than before. All this set the stage for growing discontent.

Industrialization and Growing Discontent

While Russia was largely feudal by the end of the 19th century, there was still some industrialization in the cities. Indeed, in the 1890s, the number of wage laborers increased by 75 percent, and overall industrialization increased by 25 percent. This was helped by an oil boom in Azerbaijan and the rapid growth of railways. Regardless, working conditions were terrible, with 12-hour workdays, six-day work weeks, and crowded shared living spaces for workers being common issues. This led to widespread discontent and a series of strikes. Moreover, many workers often went home to their villages for a few weeks in the spring, allowing for a sharing of grievances amongst the peasants and the urban workers. Thus, there was a unified sense of discontent amongst the lower echelons of Russian society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Reign of Tsar Nicholas II

The leader of Russia during this time, Tsar Nicholas II, did little to quell the discontent and, in many cases, exacerbated it. In 1894, Nicholas's father, Alexander III, died at 49, leaving the then 26-year-old as his heir. Completely unprepared to govern the largest land empire in the world, Nicolas II was indecisive and unable to recognize the need for systemic reforms. His reign began tragically. At his 1896 coronation, a celebration in the Khodynka field saw about 1,400 people trampled to death. While not his fault, many peasants believed this to be a bad omen. Nicholas also refused to cooperate with the more liberal and reform-minded members of the aristocracy, many of whom wanted to help the workers and peasants. All this meant that many people turned against the government entirely, fomenting a revolutionary fervor across Russia.

The Rise of Marxism

Marxism, as formulated by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, posits that a society is determined by its material base. This base is separated into two categories, the forces of production (meaning the materials and tools one has to produce things, like hand tools, domestic animals, and windmills) and the relations of production (the way the production process is organized, like slavery or wage labor). The base gives rise to the superstructure, which includes everything else in society, including politics, laws, institutions, and culture. However, the material base changes over time, resulting in a contradiction between the superstructure and the new material base. This then leads to a revolution in which a new superstructure is created. Regarding Europe in the 19th century, Marx and Engels believed that capitalism would ultimately be abolished and replaced by a communist superstructure.

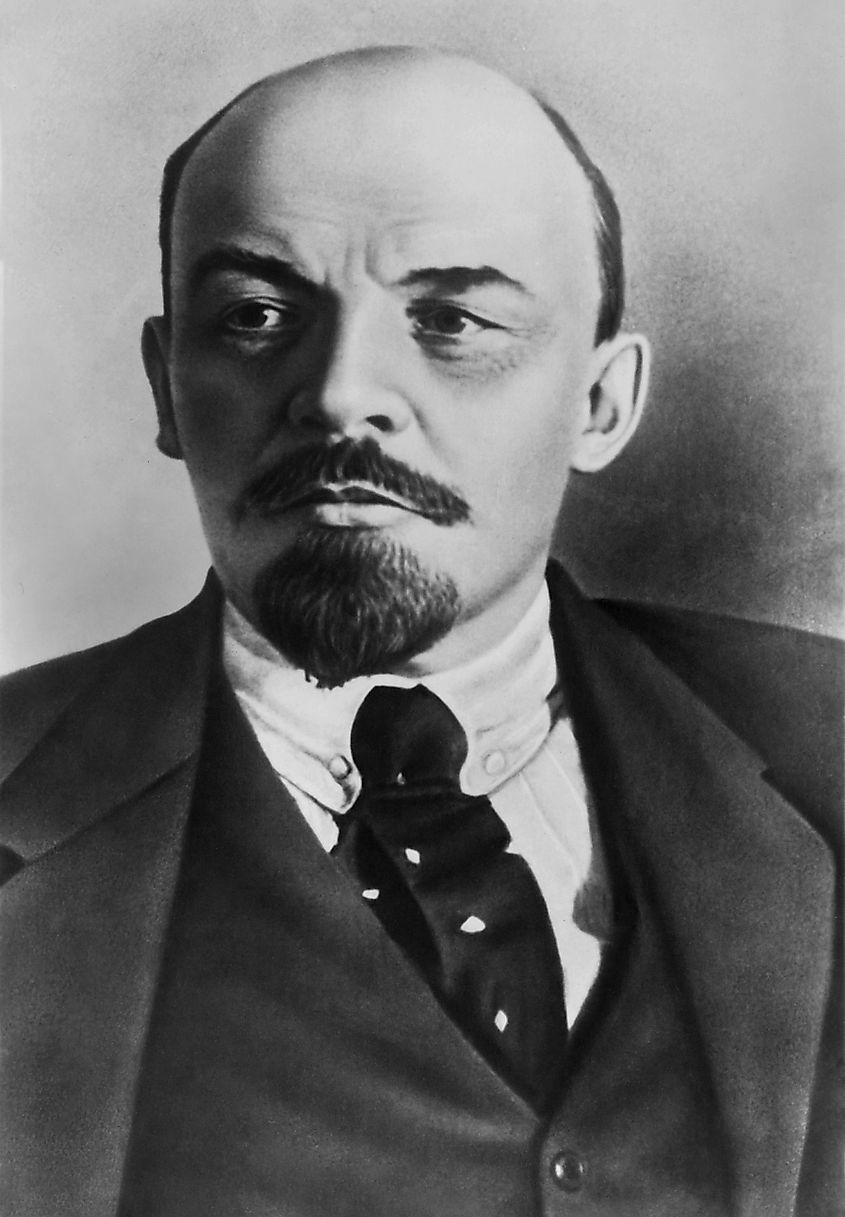

Marxism appealed to some revolutionary intellectuals in Russia, including Georgi Plekhanov. A former member of the populist and revolutionary Narodnik movement, Plekhanov formed the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in March 1898. Almost immediately, the party split into two factions, the Mensheviks and the Bolsheviks. The Mensheviks wanted to bring as many people as possible into the party. They also believed that Russia needed to fully move from feudalism to capitalism before a communist revolution could occur. The Bolsheviks, on the other hand, aimed to create a small band of full-time revolutionaries.

Furthermore, they believed that rather than fully transitioning from feudalism to capitalism, the peasants and urban workers would join to create a communist revolution. Around the same time, a third socialist party called the Socialist Revolutionary (SR) Party emerged, which combined the Russian populism of the Nardoniks with Marxism. In short, in the early 20th century, three major Marxist parties were gaining popularity in Russia. This proved an existential threat to the monarchy.

By the late 19th and early 20th century, Russia's problems were growing more dire. The sheer size of the country and its demographic diversity made it challenging to govern under ideal circumstances. Furthermore, discontent among peasants and workers made Tsar Nicholas II's weakness even more pronounced. Finally, these workers were given a movement through which to channel their frustrations with the rise of Marxist parties across the country.