What Was the Second Intifada?

The Second Intifada (the Arabic word for "uprising") was a traumatic event for Israelis and Palestinians. Emerging out of discontent from the Oslo Accords, which themselves were born of the chaos of the First Intifada, this uprising was far more violent than the first. It also contributed to, among other consequences, the end of the Israeli occupation of Gaza and Hamas becoming the ruling party of the Gaza Strip. More generally, lingering animosity from the Second Intifada continues to influence Israeli and Palestinian politics to this day.

The First Intifada and the Oslo Accords

The First Intifada began on December 9th, 1987, when an Israeli truck crash resulted in the deaths of four Palestinians. In the context of the Palestinian refugee crisis of the previous half-century, and the Israeli occupation of Gaza and the West Bank after the 1967 War, this crash ignited a years-long period of widespread civil disobedience by Palestinians. This made many Israeli leaders reconsider their handling of the occupied territories. Furthermore, the uprising also saw the Palestinian cause gain newfound international legitimacy, helped by the Palestine Liberation Organisation's (PLO) declaration of Palestinian independence, its subsequent acceptance of United Nations Resolution 242, and the perception of Palestinians being a "David" fighting against an Israeli "Goliath".

During the First Intifada, diplomatic discussions began between Israeli and Palestinian leaders. The Madrid Conference of 1991 was largely unsuccessful, but it nonetheless marked the first instance of a direct meeting of Israeli and Palestinian leaders. The far more fruitful negotiations occurred two years later in the form of the Oslo Accords. While initially promising, the implementation of the Oslo Accords proved problematic. Israeli settlers believed that Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin had given up land that rightfully belonged to Israel. Moreover, the division of Palestinian society into zones of Israeli and Palestinian control caused many Palestinians to become disillusioned with the peace process, contributing to the increasing popularity of the Islamist political party Hamas.

The Immediate Context

Despite these challenges, efforts to continue the peace process continued into the late 1990s and early 2000s. This was helped by Ehud Barak, who became the Israeli Prime Minister in 1999. In contrast to his predecessor, Benjamin Netanyahu, Barak was far more conciliatory towards the Palestinians and wanted to meet again with PLO leader Yasser Arafat to fully implement the Oslo Accords. This led to the Camp David Summit in July 2000. A "Hail Mary" attempt to finally achieve some sort of long-lasting peace, the meeting, mediated by American President Bill Clinton, was largely unsuccessful due to continued disagreements about territorial continuity, the refugee issue, and control over Jerusalem and the Temple Mount, among other factors. Regardless, all parties made plans to continue negotiations in the future.

The Second Intifada

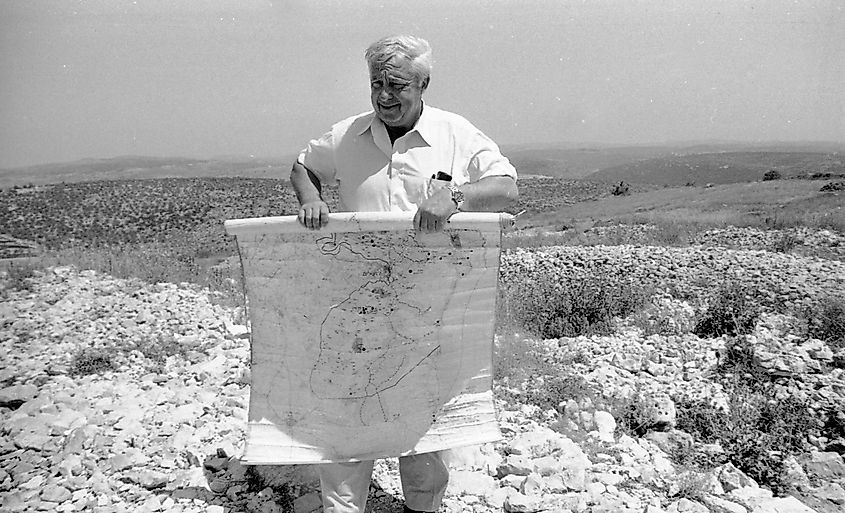

However, these negotiations were undermined by the beginning of the Second Intifada. The spark for this event was Ariel Sharon, the leader of the Likud (the opposition party to Barak's government), visiting the Temple Mount in September 2000. The holiest site in Judaism and the third holiest in Islam, Israel has claimed sovereignty over the Temple Mount and all of East Jerusalem since 1980. Sharon was accompanied by hundreds of Israeli police officers, escalating tensions surrounding an already politically charged event. This visit thus resulted in widespread protests, which quickly escalated into violence, sparking the beginning of an uprising that lasted for more than four years.

As opposed to the largely grassroots nature of the previous uprising, the Second Intifada was closer to a war between the Israel Defense Force (IDF) and Palestinian militant groups. About 3,000 Palestinians and 1,000 Israelis died, as opposed to the approximately 2,000 Palestinians and 200 Israelis that were killed in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Suicide bombing was also far more common, with around 138 instances of such attacks by Palestinian militant groups occurring between 2001 and 2005.

The End and Aftermath

In 2004, Yasser Arafat died. Mahmoud Abbas succeeded him as leader of both the PLO and Fatah, the largest political party in the PLO. Abbas, who had a good relationship with the Israelis, thought that the Second Intifada was a mistake and called for its end. While the exact endpoint of the uprising is debated, the Sharm El Sheikh Summit of 2005, in which Abbas and now Prime Minister Sharon formally agreed to end hostilities, was a notable instance of de-escalation. That same year, Israel withdrew from Gaza, thereby relocating over 8,000 settlers. However, many international organizations, including the United Nations (UN), still consider Gaza to be occupied since Israel still exercises a great degree of control over the territory. Moreover, the Israeli disengagement from Gaza proved enormously difficult, causing many to doubt the feasibility of a similar process in the West Bank.

As for the Palestinians, elections were held in Gaza and the West Bank in 2006, which Hamas won. This victory shocked the international community and Abbas, with many Western governments refusing to recognize the result. The next year saw a civil war between Hamas and Fatah, ending with Hamas taking power in Gaza and Fatah continuing to rule over the West Bank. Western governments immediately boycotted the Hamas government, and Israel and Hamas have fought wars ever since.

The Takeaway

The Second Intifada remains a crucial event in the Israel-Palestine conflict. The failure of the Oslo Accords and the Camp David Summit frustrated many Palestinians. Ariel Sharon's visiting the Temple Mount ignited these frustrations, resulting in four years of violence. The aftermath of the Second Intifada then saw Hamas becoming the governing political party in Gaza, contributing to tensions that persist today.