Islamic Golden Age

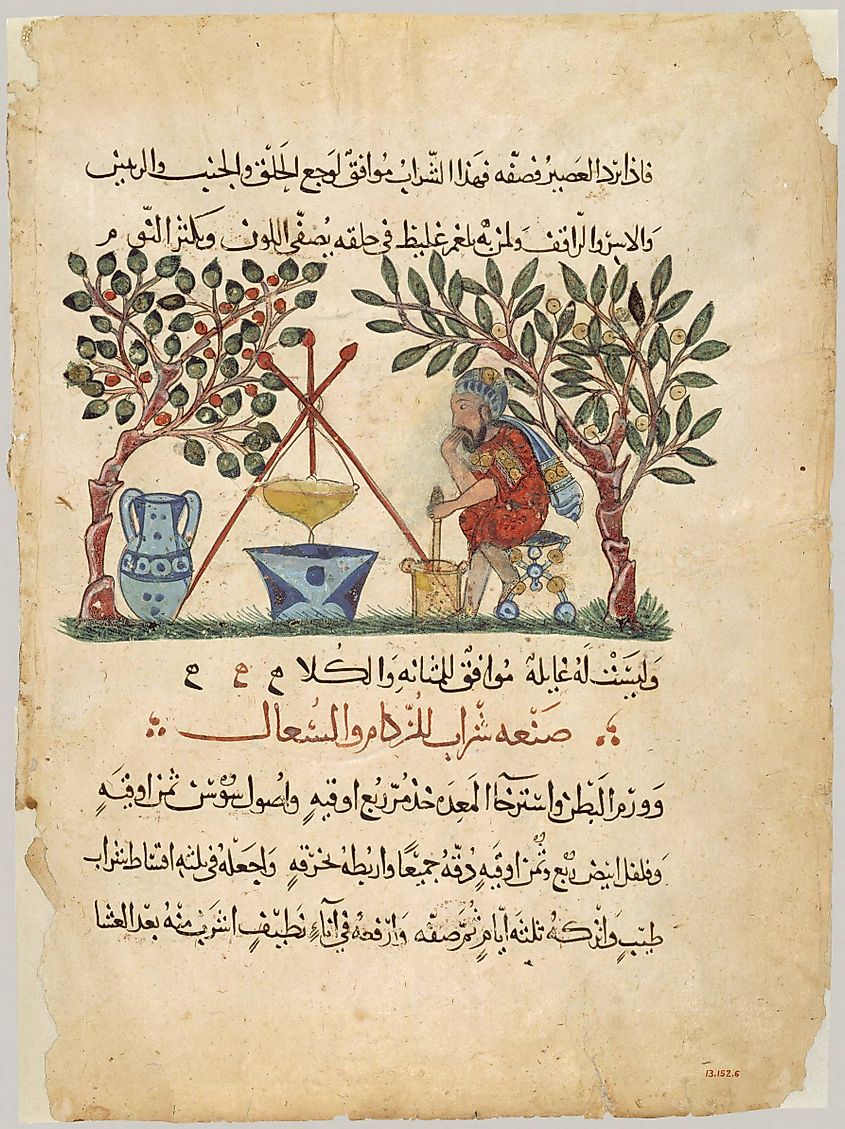

The Islamic Golden Age lasted nearly 500 years, roughly between the 8th and 13th centuries AD. During this period, monumental breakthroughs in math, literature, science, and other areas of academia were made within the various Muslim caliphates and empires that had sprung up in the Middle East, North Africa, and Spain. The Islamic Golden Age not only had a profound impact on the Muslim world but also played a pivotal role in inspiring future innovation in other parts of the world as well.

Baghdad: The Center Of Learning

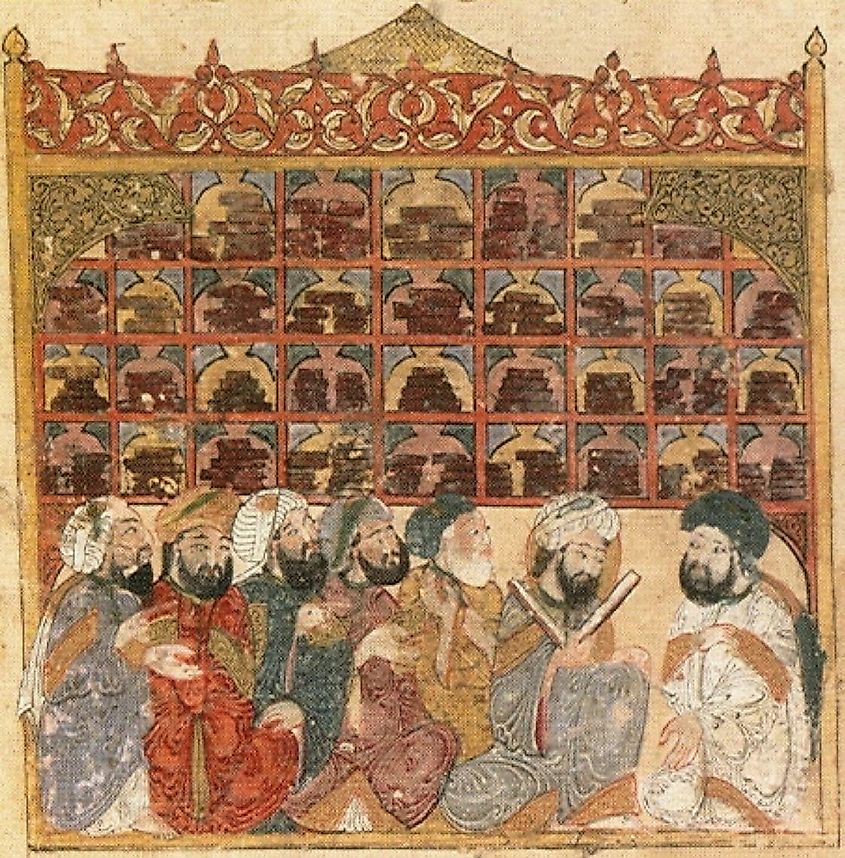

Known as Bayt al-Hikmah in the Arab-speaking world, the House of Wisdom in Baghdad was the beating heart of the Islamic Golden Age if there ever was one. First established in the early years of the Abbasid Caliphate in the 8th century, the House of Wisdom became the center of learning and education in the Muslim world for centuries. Taking inspiration from the Persian tradition that preceded it, the House of Wisdom was originally used primarily as a bureaucratic building that helped manage the day-to-day life in such a large empire. Records, local histories, and legal documents were all stored away and studied deeply by those who worked there.

In the beginning, almost all of the books that were kept at the House of Wisdom were written in Persian and needed to be translated into Arabic. It is argued by historians if these translations actually happened at the House of Wisdom or elsewhere within the Caliphate and were just brought there at a later date. Regardless, the House of Wisdom soon became a tome of knowledge not just of Persian records but also of Greek ones as well.

Baghdad thrived as an intellectual center in the early and mid-9th century under the rule of al-Maʾmūn, who personally helped the growth of this institution with his own funding and support. It was during this time that the famous mathematician Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī is credited with the discovery of early algebra.

Literacy And Education

Not only was there a surge of breakthroughs being made in academia, but large swathes of the ruling classes were also taking a serious interest in education. Literacy rates were considerably higher during this Islamic Golden Age than in other societies. While microscopically low by modern standards, it is estimated that the literacy rate within the Muslim world during this period would have been around 2%, something that would have been nearly unheard of in Dark Ages Europe and even the relatively advanced Eastern Roman Empire. Reading and writing would, of course, only be reserved for the wealthiest and most powerful members of society, but this still shows us that there was a concerted effort from rich nobles and aristocrats that they were beginning to value and appreciate a quality education.

Most learning began religiously in nature. Studying the Quran and Muslim law would have been paramount for anyone seeking an education. However, once past this stage, the study of secular records and books would have been common as well. Rulers of cities or even caliphates were often the main driving forces in education and learning during this "golden age." Either out of their own self-interest or from a genuine desire to better the society in which they lived, the end result was the same.

Religious Tolerance And Openness

The religious tolerance that this period is known for is often exaggerated or misunderstood entirely. While it is true that religious minorities were generally treated much better than they would have been in Europe, they still faced open discrimination and even violence on occasion. The idea that the Muslim Golden Age was a time of unprecedented openness often stems from the instances of certain caliphs, amirs, sheiks, or sultans who had a soft spot for their Jewish or Christian subjects. It should also be noted that even while these minority groups were protected, they still had to pay special taxes and were limited in the positions they could achieve in the government or military.

It is certainly true that during the rule of some Muslim leaders, members of minority faiths and ethnicities held significant power not only within their own communities but within the Muslim-run governments themselves, something that would have been unimaginable in other parts of the world. However, once these tolerant rulers lost power, it was not uncommon for the succeeding ruler to be just as cruel and discriminatory as any other monarch that could be found in Europe or Asia. Like many things, this topic is not a black-and-white issue but rather a very grey and murky one at best.

The End Of The Golden Age

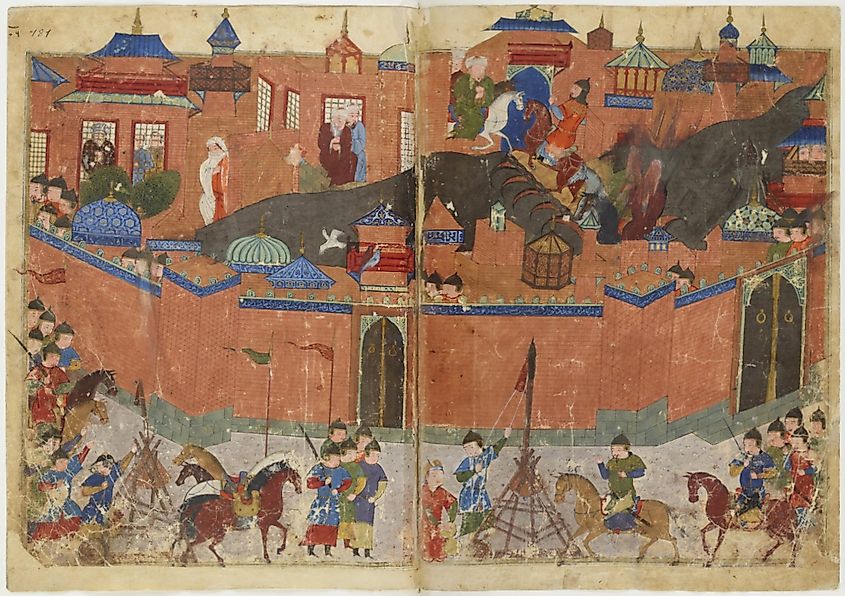

From the height of the golden age in the 9th century, vast portions of the Muslim world would continue to stress education and learning for centuries to come. This, like many other things, had ebbs and flows depending on who was ruling at the time. But, the general openness to education remained strong. All of this tragically changed in the middle of the 13th century when Baghdad, the center of the Muslim Golden Age, was brutally sacked and destroyed by invading Mongols. The city was so thoroughly decimated that the city was rendered almost unlivable for years after the invasion. The city never fully recovered and lost its seat at the head of the educational and academic world. The House of Wisdom was left a smoking ruin, and its thousands of books and endless records were all lost.

Although the Sack of Bagdad did end the Islamic Golden Age, the Muslim world would experience another age of great prosperity that would come under the rule of the Ottoman Turks in the 15th and 16th centuries. Following in the footsteps of the previous caliphates, the Ottomans, too, were great patrons of the arts and learning throughout their empire. The discoveries and breakthroughs made during this period did not just stay confined to the Middle East either. The early forms of algebra and scientific methods made their way to Europe, China, and India and were used to great success.