The Holy Roman Empire

One of Europe's longest-lasting states, the Holy Roman Empire dominated European political and military matters for much of its 1,000 years of existence. A complex web of city-states, kingdoms, empires, bishoprics, and principalities, this "empire" was more of a loose confederacy than a single unified nation. Birthed out of the endless turmoil and conflict of the European Dark Ages, the Holy Roman Empire was destined to be its own worst enemy from the start. Finally coming to an end at the hands of Napoleon in the early years of the 19th century, it is nothing short of astonishing that it could last as long as it did.

The First Emperor

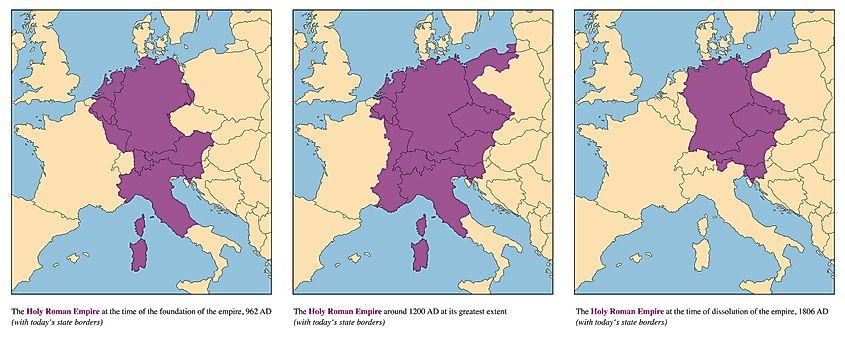

The exact date of when the Holy Roman Empire came into existence is a contested topic, to say the least. In 800 AD, after years of expansion of impressive military campaigns against pagans in what is today modern-day Germany, the Frankish king Charlemagne was crowned emperor by the Pope on Christmas Day. The lands that Charlemagne controlled were enormous, especially for the time. He had managed to bring all of France, Austria, Switzerland, Northern Italy, and much of Germany under his control, not to mention other holdings in Spain and the Balkans.

It is not clear how enthusiastic Charlemagne was about gaining this new title, and it is largely accepted that the Pope made him an "Emperor of Rome" in a not-so-subtle political move as a way to undermine the claims of the Eastern Romans (Byzantines) who still saw themselves as the rightful inheritors of the legacy and prestige of the Roman Empire since its collapse in 476 AD. The Catholic Church in Rome and the Orthodox Church in Constantinople were not on good terms and were both looking for new ways to delegitimize the other and exalt themselves as the one "true" church.

Regardless, this first iteration of the Holy Roman Empire did not last long. Charlemagne died 14 years after his coronation, and his Empire quickly descended into a brutal civil war between his three sons who inherited his lands. It would not be until 962 AD that the Holy Roman Empire would rise once again.

Early Middle Ages

After more than a century of petty wars and squabbles over territorial disputes, King Otto of Germany managed to outmaneuver his rivals and build up a large enough kingdom to deserve the title of emperor. Otto controlled both Germany and Italy and finally reintroduced a sense of order and calmness to both nations for the first time since Charlemagne all those years ago. As a gesture of his gratitude, the Pope reintroduced the title of Holy Roman Emperor and gave it to Otto.

Otto and his descendants would rule the Empire until 1024 AD, when they were replaced with the Salian Dynasty. The Salians were best known for their open questioning and challenging of the Pope's authority over the Empire. Known as the Investiture Controversy, this political upheaval was finally ended at the Concordat of Worms in 1144 AD, limiting the power and influence the church had over the Holy Roman Emperor. Both sides walked away, somewhat displeased. Later dynasties continued to push for their own power over the Empire rather than deferring to the whims of the Pope in Rome.

The Holy Roman Empire also played a large role in the Crusades starting in the late 11th century. Tens of thousands of knights, soldiers, and commoners from within the Empire would all make the long and dangerous journey to the Holy Land in numerous attempts to wrestle control of Jerusalem and the surrounding lands away from Muslim control.

Emperor Frederick I, also known as Barbarossa, was the most famous leader of this period. A skilled military leader and expert stateman, Barbarossa had fought in the Second Crusade and was poised to play a crucial role in the Third Crusade as well. Barbarossa assembled a large army and marched into Turkey. However, his attempted conquest ended abruptly after he drowned in a river while taking a bath. Much of his army disintegrated and returned home while a handful of soldiers still continued to toward the Levant.

The Imperial College

Even though the Holy Roman Emperor ruled with absolute authority, he was elected by a group of Elector Princes who made up the Imperial College. These princes consisted of the heads of the most powerful families and rulers within the various states that existed in the Empire. The title of Elector Prince was considered to be one of the most prestigious titles and only second in power next to the emperor himself. Political scheming and conspiracy were not uncommon amongst this group of princes. Both internal and external parties had vested interests in making sure whoever sat on the imperial throne would pass laws and decrees that would be in their favor.

An election would take place every time an emperor died or lost the throne for whatever reason. The ruling dynasty would often engage in backdoor arrangements and deals with the Elector Princes in order to guarantee their vote in the upcoming election. In many cases, these elections were nothing more than performative, as just about everyone else knew who was going to be elected emperor well before the election was even announced. The Habsburgs, a royal family hailing from Austria, dominated the imperial throne from 1493 to 1711. Not only were they able to hold on to the title Holy Roman Emperor for centuries, but they also placed other family members on the thrones of other European nations such as Spain.

Political Structure

The Holy Roman Empire was nothing like the modern nation-states of today. The Empire, if it could even be called that, was made up of hundreds of smaller states, all of which had their own interests and desires. As one could imagine, the wants of one state did not always align with another and vice versa.

Wars between member states were quite common as kings and barrons waged wars against one another over what were often trivial grievances at best. The conflict against other European kingdoms was not out of the ordinary either. It was expected that the emperor, along with all of the other states in the Empire, would come to the aid of one another in the event an outside force attacked them.

As chaotic as the Holy Roman Empire was internally, it did seem to rise to the occasion when it faced a mutual and foreign enemy. If each local-level ruler cooperated, the Holy Roman Empire could field an impressive and robust army that could match the military might of any other European power. France and the Holy Roman Empire fought numerous wars against one another over land disputes in the Low Countries and Burgandy. French attempts at invasion ended in defeat more times than not.

Culture And Identity

The Holy Roman Empire was largely made up of German-speaking states. While this might give off the impression that this Empire was largely homogeneous, this could not be further from the truth. Even though many of the Empire's citizens shared a common language, a shared culture and identity were almost non-existent.

Most German speakers at the time resonated much more with their local and regional sense of identity rather than some vague and nebulous idea of national belonging. The majority of common folk lived and died without traveling far outside of their place of birth, and it would have been next to impossible for them to relate to anyone outside of this bubble, regardless of what language they spoke.

The Empire also consisted of other ethnic and linguist minorities such as the Dutch, Poles, Danes, Flemish, French, Swiss, Italians, Slovaks, Sloviens, Czechs, Hungarians and many more. While this did sometimes result in flare-ups of ethnic tension and violence, the biggest dividing factor in the Empire would ultimately become religion.

Protestant Reformation

Beginning in 1517, in Wittenberg, a German monk named Martin Luther published his writing titled Disputation on the Power of Indulgences. His work was in direct contradiction of the teachings of the Catholic Church and was an open challenge to their authority. Broadly speaking, Luther claimed that the church was not needed to act as an intermediary between a worshiper and God. Luther asserted that the relationship between God and man was deeply personal and did not require the supervision of bishops, clerics, or even the Pope himself to guide Christians.

The beliefs of Luther would spark over a century of political upheaval and a series of catastrophic wars that would nearly end the Holy Roman Empire altogether. These religious conflicts would culminate in the near-apocalyptic Thirty Years' War that claimed the lives of a third of the Empire's population and left large swathes of Continental Europe in utter ruin.

The Treaty of Westphalia ended the war in 1648. In the following decades, the Holy Roman Empire made considerable efforts to try to recover but would never return to the same level of power and prestige that it once had. Not only would foreign powers such as France grow in power and strength but the Empire was now facing a new threat from within the Empire itself. Prussia.

The Rise Of Prussia And The Napoleonic Wars

Prussia, a small German state that had risen out of Northeastern Germany and Northern Poland had been steadily growing in power and influence over the centuries. By the middle of the 1700s, Prussia had managed to assemble what some consider to be the most formidable military in the world. The Prussian king openly challenged the authority of the Holy Roman Empire as it annexed its smaller neighbors and fought off any armies that were assembled to stop them. Imperial authority was clearly on the decline.

The final blow would come at the hand of none other than Napoleon Bonaparte. In 1805, the French general led an army deep into the Holy Roman Empire and crushed its military. The emperor was forced to admit defeat, and in 1806, the Empire was officially dissolved. After Napolean was finally dealt with in 1812, what remained of the independent German states joined the newly founded German Confederation headed by Prussia and Austria-Hungary. While it might have seemed as though these small states were acting on their own accord, they were, in practice, nothing more than vassals to the Prussians, who eventually absorbed them all by 1870 and formed the German Empire.

The Holy Roman Empire was a deeply complex and troubled union of people with diverging interests and values. At times, it was one of the most dysfunctional and chaotic states within Europe (which is really saying something), and at other times, it could dominate the continent both militarily and culturally.

In the end, it was not a foreign invader that crushed the Empire, but it was a growing and ambitious kingdom from within that would ultimately lead to its downfall. The Holy Roman Empire was able to reign supreme in the times of Feudalism and the Early Modern Period, but by the time various nationist movements in the 19th century took hold, it was only a matter of time before the small remnants of the Empire were swallowed up either by Prussia or Austria.