The Late Middle Ages and the Decline of European Stability

The Middle Ages (roughly 500 to 1500 CE) saw a very different Europe than the one today. Rather than state rule being recognized above all else, there were competing claims of authority by the nobility, the monarchy, and the Catholic Church. Moreover, Europe's economy was largely agricultural, and about 90 percent of the population lived in tiny villages. Despite these differences, life throughout most of this period was relatively stable. However, this changed in the 1300s with a wave of political instability, religious upheaval, and widespread death caused by disease and famine. Over the course of the next two centuries, the continent was fundamentally transformed, paving the way for the early modern period.

The Great Famine

From 1315 to 1317, a major famine struck Europe. It was mainly caused by unusually heavy rain in the spring of 1315, which made it difficult for grain to ripen. The resulting crop failure led to food prices increasing dramatically--for example, doubling in England and rising 320 percent in Lorraine. By the summer, peasants across the continent had begun to starve. According to some accounts, King Edward II of England was also unable to find enough food. Heavy rain continued in 1316, followed by more starvation and rumors of cannibalism. The worst came in 1317 when, despite weather patterns normalizing, crop yields remained low due to a weakened peasantry and a depleted seed stock. Thus, only by 1325 did food supplies return to normal.

The Great Famine marked the end of centuries of consistent population growth in Europe, with estimates putting the population loss in urban environments at around 10 to 15 percent. Furthermore, it weakened the general populace, meaning that they would be more vulnerable to future catastrophes.

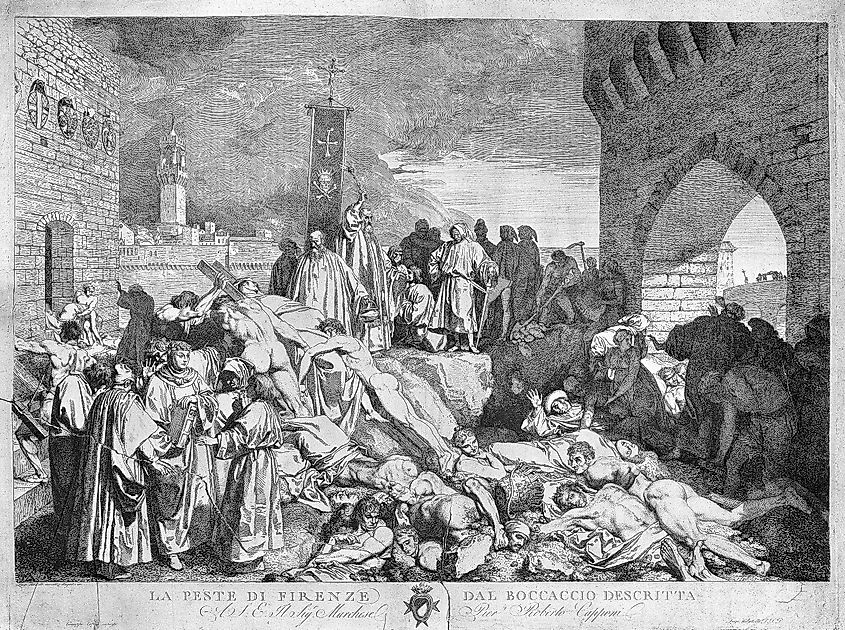

The Black Death

One such catastrophe was the Bubonic Plague, also known as the Black Death. Originating in China, it reached Europe when the Mongols besieged the Crimean city of Kaffa in 1347 and catapulted plague-infested corpses over the walls. Thereafter, the disease spread, reaching Sicily in 1347, Spain, Italy, France, and England in 1348, Austria, Switzerland, Hungary, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg in 1349, and Scandinavia and the Baltic states in 1350.

The impact of the Plague was profound. Antisemitism grew as Jews, a popular scapegoat throughout European history, were blamed for the disease. Trade and wars also basically stopped during the pandemic. Finally, between 75 to 200 million people died worldwide, including about 30 to 60 percent of Europe's population.

Those who survived largely found themselves amidst better living conditions, as fewer people meant less stress on food supplies, leading to increased birth rates. When combined with agricultural advancements and investments in infrastructure by monarchs, urban areas began to grow rapidly. Hence, the Black Death fundamentally transformed Europe by changing how many people lived, pushing the continent towards the early modern period.

Popular Revolts And Wars

The period from 1300 to 1500 also saw numerous wars and revolts. For example, excessive taxation led to the Flemish Revolt (1323 to 1328), which eventually escalated into a full-on rebellion. The English Peasants' Revolt occurred in 1381 due to, among other reasons, the economic consequences of an ongoing war with France and general political instability. Finally, the Transylvanian Peasant Revolt lasted from 1437 to 1438, another taxation-based uprising.

Regarding wars, the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453 marked the end of the Byzantine Empire (also known as the Eastern Roman Empire). Furthermore, the Hundred Years' War (1337 to 1453) between England and France occurred due to competing claims over the heir to the French throne. While the conflict ended in a French victory, it resulted in the growth of nationalism across Western Europe and military innovations like the widespread usage of professional standing armies. In fact, all these wars and many of these revolts helped bring about fundamental changes in Europe's political and military spheres.

The Western Schism

The Western Schism began in 1378 when two bishops, one in Rome and one in Avignon, claimed to be the true Pope. The situation was further complicated in 1409 by another claimant in Pisa. Rather than being the result of theological disagreements, the three Popes were driven by political allegiances and personal gain. The schism eventually ended in 1417, with the Roman and Pisan claimants renouncing their titles and the excommunication of the claimant from Avignon. Thereafter, a new Pope, Martin V from Rome, was elected.

Despite reunifying, the inability to decide on a leader for decades eroded the Catholic Church's legitimacy. When combined with anger due to abuses of authority by the clergy, this ultimately led to the Protestant Reformation in the early 1500s. The Reformation thereby singled a permanent split in Western Christianity and over a hundred years of religious-based conflict between Protestants and Catholics.

The Late Middle Ages were a period of profound transformation in Europe. Whereas for centuries prior, life was fairly stable, the Great Famine, the Black Death, the Hundred Years' War, and the Western Schism rocked the foundation of European society. Indeed, all these events contributed to the end of Medieval Europe, bringing the continent into the early modern age.