The Mongol Empire

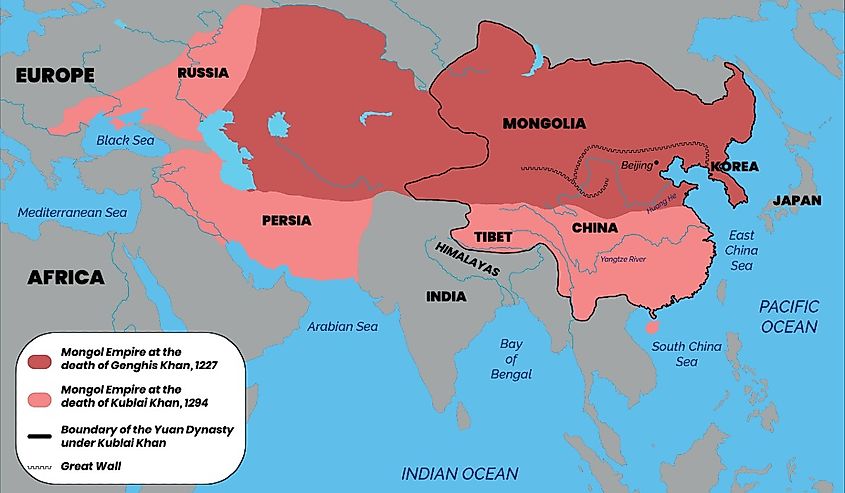

The Mongol Empire was the largest contiguous empire the world has ever known. Stretching all the way from Korea to Hungary, the sheer size of the Mongol Empire is hard to comprehend. For more than a century, there was not another nation that could even come close to the Mongols in military capability. During their height in the 13th century, they were unstoppable.

Even though the empire would fracture into various regional powers not long after it was established, the legacy that the Mongols left behind would far outlive their actual empire. The Mongols were not just genius innovators on the battlefield but also ushered in a long period of peace and relative stability in the Middle East, Russia, China, and Central Asia.

Origins and Expansion

The Mongols, before the formation of the empire, consisted of dozens of various tribes that all inhabited the lands to the northwest of China. These tribes spoke the same language and shared similar cultural practices and religions but were loyal to their own tribe members rather than to some notion or idea of a unified Mongol people.

Famous for their nomadic lifestyle, the Mongols did not live in permanent settlements but rather moved around several times each year either in pursuit of herd animals or in search of new grazing lands for their sheep and goats that lived with them. Much of the Mongol diet consisted of sheep and goats, but they were also known to feast on horses as well.

The horse was an integral and irreplaceable part of Mongol society. Horses allowed the Mongol tribes to traverse the steppe with relative ease and made hunting wild animals much easier. Horsemanship and archery were valued skills. The Mongol horse archer was their greatest weapon against the footsoldiers of their enemies.

Genghis Khan

Born as Temujin, like many other Mongols, the early life of Genghis Khan was not easy. By the age of 10, Genghis' father died at the hands of a rival tribe, and his own people abandoned him along with his mother and six siblings. He and his family struggled for the next few years, living on their own in the vast Mongol wilderness. It is not entirely clear, but it is largely accepted by historians that Genghis killed his own brother in a "hunting accident" so he could gain full control of his household. Once he was a teenager, he married his first wife, Borte.

His marriage to Borte gave Genghis just enough respect in Mongol society for him to start forming alliances with other tribes. Genghis built up a reputation as a skilled and fearless warrior during his early adult life and slowly began to conquer and incorporate neighboring tribes into his realm. Khan disregarded previous traditions and assigned generalship and other key roles in his government based on ability rather than family relations or kinship. Khan often had the ruling members of an enemy tribe killed once they were defeated and then assimilated the enemy tribesmen into his own army.

In 1205, Genghis Khan brought every Mongol tribe under his control and was officially labeled Chinggis Khan or "Universal Leader." He now ruled over a landmass that was roughly the same size as modern-day Mongolia and was ready to expand his Khanate's borders.

Expansion and Conquest

With Mongolia now unified under one ruler, it was not long before the Mongols looked outside of their own borders to conduct raids and conquer new territory. The first victim of the Mongols was the Xi Xia kingdom, located in Northern China. In 1209, the Mongols stormed towards the Xi Xia capital of Yinchuan and besieged the city. The Mongol army was made almost entirely of horsemen, and they had nothing in the way of siege engines such as catapults and mangonels. Despite this clear disadvantage, the Mongols encircled the city and eventually forced the ruler of Yinchuan to surrender and become a tributary.

The nearby Jin Dynasty was not unaware of this burgeoning power to its north and demanded that Genghis Khan submit to the authority of the Chinese Emperor. Khan responded by attacking the Chinese and launching a series of devastating raids deep into Jin territory between 1211 and 1214.

By 1214, the Mongols had reached the city of Zhongdu (Beijing). The ruler of the Jin agreed to pay the Mongols tribute in the form of gold and silk but then moved his capital from Zhongdu to Kaifeng, something that Genghis Khan felt was a breach of their agreement. In response to this supposed betrayal, the Mongols, with the aid of Jin deserters, sacked Zhongdu and killed or enslaved most of its population.

Into Central Asia

Khan now controlled much of China along with his traditional holdings in Mongolia. Looking eastward, Khan hoped to form an amicable relationship with the Persian rulers of the Khwarezm Empire, which ruled over much of Central Asia and Iran. A trade agreement was set up between the two powers. However, when the first Mongol caravan arrived, the goods it was carrying were stolen, and the merchants and envoys were executed and had their heads sent back to Khan.

Enraged at this great treachery, Khan marched his army into the Khwarezm Empire and inflicted unspeakable atrocities against its people. Skilled laborers were often spared, but the rest of the population was slaughtered. While the Mongols had encountered difficulties besieging walled cities only a few years prior, they had no issues in Persia thanks to skilled Chinese engineers that they pressed into service from their newly conquered lands. The Mongols made short work of the fortified cities of Samarkand and Bukhara and killed many of the inhabitants.

Only two years after the invasion had started in 1219, the entire Khwarezm Empire was under the control of the Mongols. It is estimated that nearly 2.5 million people died due to this invasion, but the exact numbers are hard to verify.

Tactics

The Mongol army was often outnumbered but worked around this shortcoming by using their superior maneuverability and speed to their advantage. Each time they would attack a city or walled settlement, the mounted Mongol warriors left long before the enemy could muster any kind of response. These hit-and-run tactics became a famous staple of Mongol doctrine in the later decades and centuries.

The Mongols were also well known for feigning retreats in the face of a numerically superior enemy. The enemy army often pursued the Mongol force, thinking they had the upper hand, only to end up in an ambush. It was not uncommon for the more traditional armies that the Mongols faced to chase them for days at a time. Only once the pursuing army was exhausted, disorganized, and cut off from their own supply lines would the Mongols turn to fight. The result was often nothing short of a massacre.

Genghis Khan's Death and Legacy

Genghis Khan returned to Mongolia in 1225, in control of the largest empire in the world. The Xi Xia had refused to provide troops for the invasion of the Khwarezm Empire, and Genghis and his generals decided this blatant disrespect for Mongol rule could not go unpunished. Khan led an army into Xi Xia in 1227, but he did not see much of the campaign. The same year, Khan fell from his horse and suffered serious internal injuries not treatable by the medicine available at the time. On August 18, 1227, Genghis Khan died.

The empire that Genghis forged was far from its height in power and influence. The Xi Xai was crushed soon after his death, and Khan's sons were more than capable of carrying out their own conquests. All of China, Korea, Vietnam, Central Asia, the Middle East, and Russia fell under Mongol rule in one way or another in the coming decades.

Governance and Administration

The vast territory of the Mongol Empire at its height was impossible to manage directly by one man. The Mongols were not oblivious to this and made sure to give most of the governing responsibilities to local rulers, who were obedient servants to the Mongols. As long as the local rulers left in power paid their taxes and any other forms of tribute on time, then they were largely left alone.

The later Mongol rulers, such as Genghis Khan's grandson Kublai Khan, ruled over China with surprising efficiency. He simplified taxes, and Kublai set up a formidable postal service that allowed not only generals and government officials to communicate with relative ease but also made the lives of merchants much easier. By the time of Kublai's death, there were more than 1,400 postal stations across his territory. Agricultural reform was another success of Mongol rule in China. Kublai went as far as to establish the Office for Stimulation of Agriculture. This government body was tasked with maximizing the output of Chinese farms and ensuring that its people would not suffer from famine.

Kublai established hundreds of new granaries across China and reorganized farmers into groups called "she," which were usually made up of roughly 50 families. These groups of farmers were hyper-focused on a smaller plot of land but were also encouraged to plant trees, prevent flooding, stock nearby rivers with fish, and work on silk production. This new system was a resounding success and led to the widespread knowledge of advanced agricultural techniques across China.

Culture and Society

Daily life in the Mongol Empire was different depending on where you lived. The Mongols were some of the most savage and ruthless conquerors the world has ever known but were tolerant of the cultures and faiths of the people they conquered. The Mongols worshiped a sky god named Tengri. Tengri can be more accurately described as a personification of the world and the universe rather than a god but the Mongols made little qualms about this distinction not being made by outsiders. The Mongols did not seek to convert others to their faith and had no expectations that foreigners would even be interested in learning about their religion. As the empire grew in size and reach, many Mongol courts employed the help of Muslims, Buddhists, Christians, Jews, Hindus, and many others to run the empire.

The Mongol Empire had always comprised dozens of religious and ethnic groups. All of them had the autonomy to live how they liked. As long as it did not interfere with or challenge Mongol rule, the Mongols were completely indifferent to how their subjects conducted their day-to-day life. As the centuries passed and parts of the Mongol Empire began to drift further away from their roots, many of the Mongol ruling families began to assimilate into the cultures of the people that they conquered. For instance, many of the Mongols that settled in Persia and Central Asia after the conquest of the Khwarezm Empire eventually converted to Islam and, within a few generations, became almost indistinguishable from the native population.

The cultural influence of the Mongols was even seen in areas of their empire that had always been rebellious and difficult to manage. Russia, a stubborn and disobedient part of the Mongol Empire, even adopted Mongol culture, particularly on the battlefield. Much of the Russian weapons and armor made under Mongol rule had a distinct "eastern" feel to it that made it stand out from other European nations.

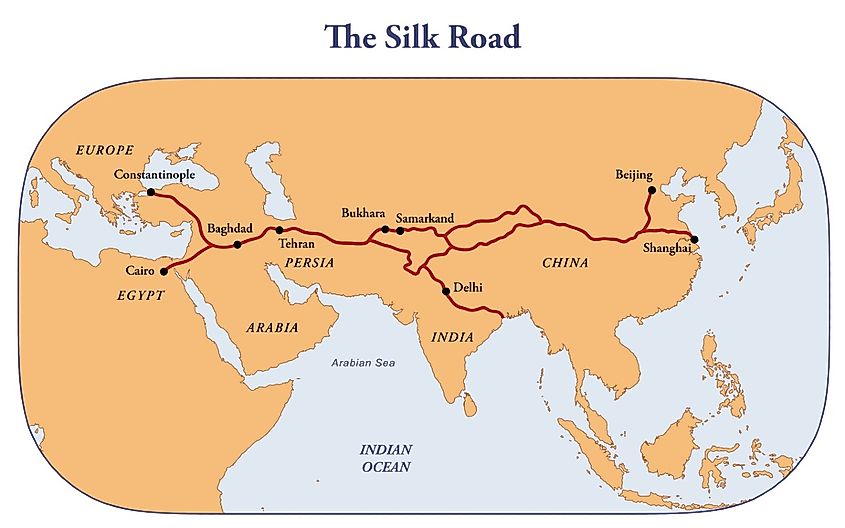

Mongols and the Silk Road

The Silk Road is a title often used to describe the intricate trade networks that existed between Europe, the Middle East, and East Asia. First emerging some time in the 1st century BCE, silk from China was transported overland across Central Asia, through the Middle East, and eventually into Rome or Constantinople. Other goods were transported through these trade networks, but it was Chinese silk that was the most sought-after and most valuable. It was almost unheard of for a single merchant or caravan to make the whole trip on their own. Most of the merchants who used the Silk Road would usually only travel to one or two cities, sell their goods, and then return home.

The Silk Road had its own ebbs and flows throughout its long history and saw its "golden age" during the height of the Mongol Empire in the 13th century. Sometimes referred to as the Pax Mongolica or Mongol Peace, this period of history saw unprecedented levels of trade and wealth moved across the Silk Road. The Mongols made protecting trade one of their top priorities as rulers. The Silk Road was so safe during Mongol rule that a man could walk from one end of the route to another with a gold plate on his head and not have to worry about being robbed or killed. The Mongols were harsh in battle but established law and order wherever they conquered.

Perhaps the most famous traveler of the Silk Road was none other than the Italian merchant Marco Polo. While it is still debated by some historians if Polo ever actually made it to China or not, it is almost certain that Polo and his family made it a considerable way across Asia. Regardless, the stories and writings that he produced when he returned from Italy made him famous and enthralled many of Europe's rulers with tall tales of the Far East. Not only did trade flow across the Silk Road, but so did new technologies and ideas. The invention of gunpowder in China, along with other inventions, made its way into Europe and the Middle East thanks to this trade network.

The Decline and Fragmentation

By the time the Mongols controlled all of China and established the Yuan Dynasty, the Mongol Empire had effectively split into four distinct regions. The Ilkhanate controlled Persia and large areas of the Middle East. The Chagatai Khanate controlled Central Asia. The Golden Horde lauded the various princes and kingdoms of Russia and Eastern Europe. And lastly, the Yuan Dynasty dominated China and Korea.

While all of these Khanates were under the leadership of Kublai Khan, in reality, these parts of the empire were together in name only. In practice, they functioned and acted as completely separate nations. The empire was simply too large for one man to rule. The Yuan Dynasty eventually came to an end in the late 14th century, ending any kind of formal Mongol Empire. The fragmented sections of the empire continued to survive for the next few centuries before eventually falling victim to their neighbors, who often surpassed them in military technology.

In an ironic twist of fate, Russia, once a Mongol vassal, went go on to conquer and subjugate most of the nomadic peoples who once ruled over them. The Golden Horde was the first to fall in the 15th century, but Russia gradually expanded eastward, slowly taking control of Central Asia. These nations remained a part of Russia in one way or another until the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s.

Legacy of the Mongol Empire

Like many other empires, the legacy of the Mongols is long and complicated. On one hand, they brought a level of indescribable terror and destruction to the world around them. Not only did they burn entire cities and nations down to the ground, but they were also responsible for the destruction of countless centers of education from this era, along with an incalculable amount of cultural artifacts. The sacking of Baghdad in 1258, for instance, was so thorough and meticulous that it arguably destroyed the city to such a point that it never fully recovered, even to this day. This desolation of Baghdad also brought about a catastrophic and emphatic end to the Islamic Golden Age.

The Mongols were also competent statesmen and just rulers relative to their time. There was no other place on Earth that was as tolerant of alien faiths and accepting of foreigners as the Mongol Empire. They also embraced meritocracy rather than assigning high-ranking offices based on royal bloodlines or tribal allegiance. The economic boom their rule ushered in also brought about a level of wealth and prosperity that parts of the world had never seen and, in some cases, would never see again.

Perhaps the largest legacy that the Mongols left behind was the unintended consequences that sprouted from its empire. Without the revitalization of the Silk Road, it is unlikely that the Black Death would have ever made its way to Europe. The subsequent fallout from the Black Death changed Europe forever and began the slow and gradual process of moving away from feudalism and towards the early stages of building what would one day become a middle class.

Without the Mongol invasion of the Middle East, it is likely that the Ottoman Turks would have never settled in Anatolia and then gone on to create one of the greatest empires of the modern age. The eventual capture of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453 shut Europe out of the Silk Road and forced them to look West for a new overseas root to China. While the Mongols did not build any great cities or leave us with many spectacular monuments, the ripple effect left by their brief yet great empire is felt and seen in the modern world today.