How the Troubles Began in Northern Ireland

The Troubles were a period of low-intensity warfare in Northern Ireland that occurred from the late 1960s to the late 1990s. Fought between the Protestant Loyalists (or Unionists), who wanted the country to remain in the United Kingdom (UK), and the Catholic Republicans (or nationalists), who desired independence and reunification with the rest of Ireland, the conflict saw over 3,500 deaths. However, the roots and causes of the war go back hundreds of years. Thus, to truly understand the nature of the Troubles, investigating their origins is necessary.

Background

In 1609, Scottish and English settlers began to immigrate to what would eventually be known as Northern Ireland. Being predominately Protestant, they clashed with the local Catholic population. The resulting tensions led to the Irish Confederate Wars of 1643 to 1653 and the Williamite War of 1689 to 1691. Thereafter, the failed Irish Rebellion of 1798 saw Republicans, influenced by the American and French Revolutions, rise against British rule. Nonetheless, the Act of Union 1800 saw Ireland formally incorporated into the UK. This event was followed by the rise of the Irish Home Rule movement in the late 1800s, which pushed for independence from the Crown.

Rising Tensions

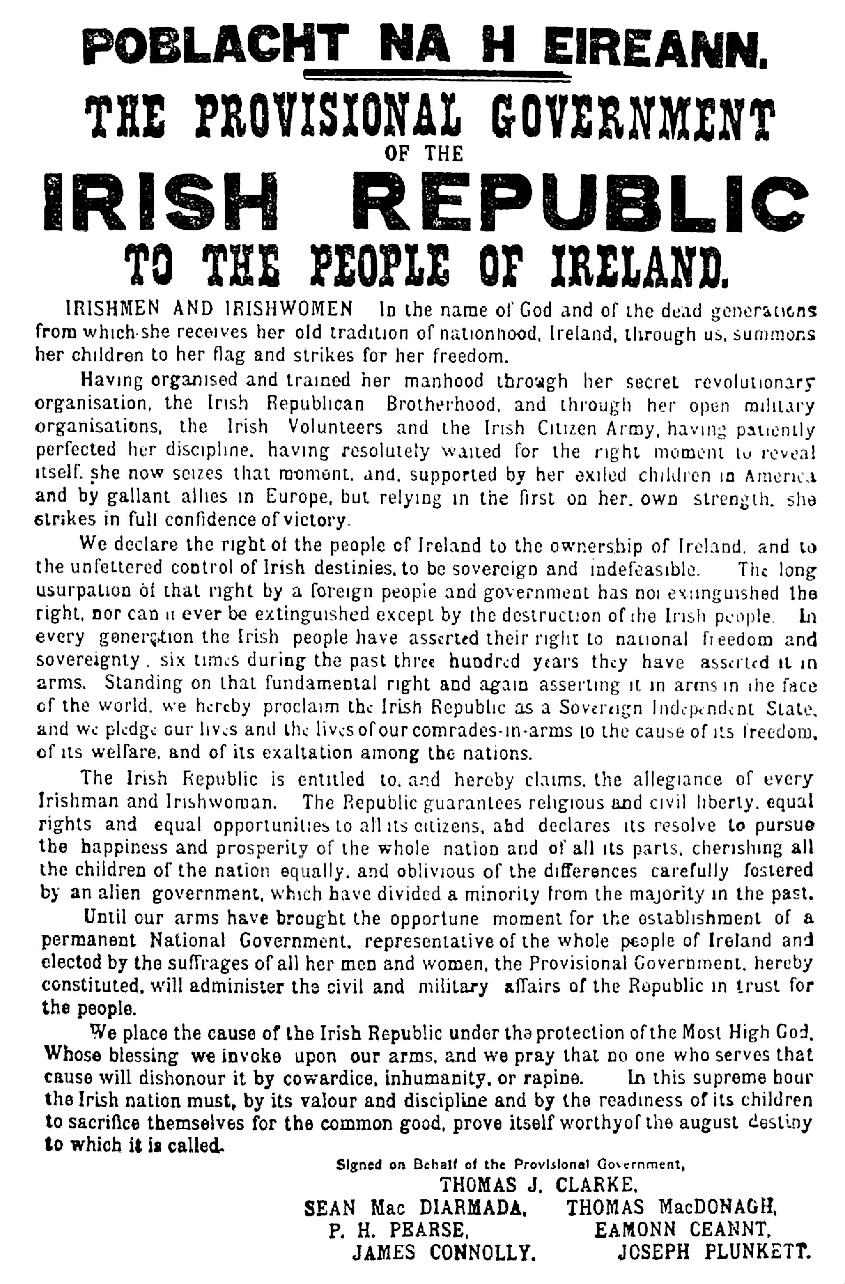

As World War One broke out in 1914, Ireland found itself divided between Loyalists, who fought for the UK, and Republicans, who refused to go to war. Since these nationalists stayed home, they were able to launch an uprising in April 1916. Despite this "Easter Rebellion" failing, the separatist party Sinn Féin won the 1918 election. The Irish War of Independence subsequently broke out between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and British forces from 1919 to 1921, resulting in an Irish victory. A brief civil war then ensued due to disagreements over the independence treaty, ending in a victory for the pro-treaty side.

Crucially, in the 1918 election, Sinn Féin did poorly in the north. Therefore, as allowed for by the independence treaty, Northern Ireland opted out of the newly created Irish state. However, many Catholics in the north were angered by this division, leading to sectarian violence. One of the most notable instances of this anger manifested itself on July 10, 1921, when over 200 Catholic homes were destroyed or damaged by grenades and Molotov cocktails. Incidents such as these occurred over the next fifty years before finally escalating in the late 1960s.

The Beginning Of The Troubles

There is much debate over exactly when the Troubles began. Some assert that they started with the rise to prominence of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), a Protestant extremist paramilitary organization, in the Shankill region of Belfast. Indeed, in March and April 1966, Republicans paraded throughout the city in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the aforementioned Easter Uprising. Partially in response to these demonstrations, the UVF, led by former British solider Gusty Spence, burned several Catholic homes, businesses, and schools. Soon afterward, the UFV declared war on the IRA.

The next few years saw rising tensions between Unionists and Republicans. For instance, in June 1968, several Republicans, including the member of Parliament Austin Currie, squatted in Caledon to protest housing discrimination against Catholics. Their subsequent arrest prompted widespread protests. Then, Unionists bombed electricity installations in March and April 1969 and blamed them on the IRA. These attacks weakened support for Prime Minister Terence O'Neill, a moderate Unionist, and he thus resigned on April 29, 1969.

Tensions culminated on August 12, 1969, when the Protestant Apprentice Boys marched by the Catholic Bogside neighborhood in Derry, commemorating a battle in the Williamite War. Such a display insulted the residents, leading to onlookers throwing stones and nails at the passersby. This soon escalated into a full-on riot known as the Battle of Bogside. Before long, riots had engulfed the entire country, and British troops were deployed to restore order. The Troubles were now unambiguously underway.

The next three decades were a period of constant conflict. For example, January 20, 1972, known as Bloody Sunday, saw British troops kill 14 unarmed Catholic protestors. The 1980s and 1990s also saw numerous shootings, bombings, and kidnappings, among other atrocities. Ultimately, the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 ended the Troubles, with power-sharing between Catholics and Protestants being established as a key principle moving forward. However, despite this relative peace, centuries of conflict persists in the Northern Irish historical memory.