The Arab Revolt of 1936-1939

The 1920s and 1930s were a time of tension in Palestine. Under British rule due to the League of Nations mandate system, this period saw conflicting developments between emerging Palestinian nationalism and the ever-expanding infrastructure for a Jewish state. When paired with anti-British sentiments amongst the Arab population, conflict was seemingly inevitable. Indeed, all these factors culminated in the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939.

Background

After World War I, the United Kingdom (UK) came to control Palestine under the League of Nations mandate system. The supposed aim of this system was to guide political entities that were not yet ready for statehood toward independence. However, during the war, the British also promised the Jews a state in Palestine via the Balfour Declaration. This meant that there were competing Jewish and Palestinian national identities during the mandate period.

Tensions initially flared in the 1929 Wailing Wall Riots, which saw violent protests by both the Jews and Arabs, as well as violent measures to quell the protests by the British. Despite initially seeming that some of the promises of the Balfour Declaration would be scaled back due to these riots, pressure from the Jewish Agency in London caused these plans to be reversed. When paired with increased Jewish immigration to Palestine in 1933 following the rise of the Nazis, as well as building anger towards the British due to their colonial practices, this set the stage for more Arab unrest.

The Beginning

In 1935, Izz ad-Din al-Qassam, a militant Palestinian nationalist and anti-Zionist, was killed by the British. This prompted a wave of violence and other protests against the Jews and the British. Around the same time, grassroots general strikes began in Jaffa and Nablus, contrary to the wishes of the Arab elite.

Indeed, the notables, wealthy landowning peasants under the Ottoman Empire who were subsequently put in positions of power during the mandate period, created the Arab Higher Committee in April 1936 to help negotiate with the British to end the demonstrations. This was largely for economic reasons. While some notables shared the demonstrators' anti-Zionist and anti-colonial inclinations, ending the strikes by October was crucial to ensure they had workers for the autumn harvest. British troops did manage to somewhat quell the violence by the end of the year. Regardless, assassinations and arson bombings occurred throughout the first half of 1937.

The Peel Commission

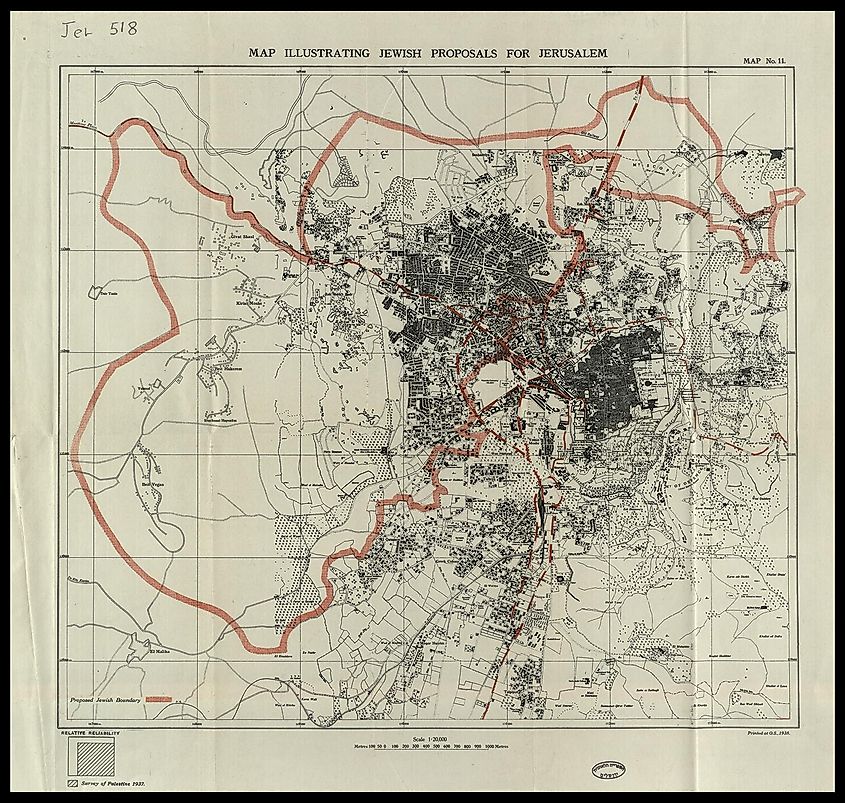

To discover the cause of the revolt, the British launched a commission. Run by Lord Robert Peel, it stated that the mandate was the root of the problem and needed to end. Fostering two different nationalist movements in the same territory had proved untenable, necessitating a land partition. The Peel partition plan aimed to create as much territorial continuity as possible for the proposed Jewish state. However, separating the Arab and Jewish populations on the ground was impossible, meaning that the Jewish state would have only had a 55% Jewish majority. Therefore, there were talks of population transfers.

Furthermore, since the Jewish state would have received most of the agriculturally viable land and the best infrastructure, the Peel Commission concluded that the Arab state should enter into a federation with Jordan. Once the Arab population heard about these plans, violent unrest reignited in the second half of 1937, lasting until 1939 when the British regained control through the usage of draconian martial law measures. Indeed, by the end of the revolt, one in ten Palestinian leaders had been killed.

The White Paper and Aftermath

The British created yet another commission in 1938. Known as the Woodhead Commission, it stated that the Peel partition plan was not feasible due to the impossibility of enacting a voluntary population transfer. This thus led to the White Paper in May of that same year, which stated that Jewish immigration would be limited to 75,000 for the next five years, after which it would be subject to the decision of the Arab majority. Furthermore, Jewish land purchases were to be restricted to particular areas of Palestine. Finally, influenced by Wilsonian ideas and the recent independence of Egypt and Iraq, plans were made for an independent Palestine in ten years. In short, the White Paper marked the seeming end of plans for a Jewish state in the region.

Final Thoughts

The Arab Revolt was a seismic event. Emerging from the tensions inherent in colonial rule and having two competing national identities vying for statehood, it ultimately caused a reversal in British policy towards the creation of a Jewish state. However, the ramifications of this reversal never became clear due to the enormous shift in the international landscape caused by World War II and the Holocaust.