South America's Battle With Droughts That Cause Wildfires

Over the last decade, South America has grappled with a number of harsh, frequent droughts. This upswing in dry spells has sparked an alarming number of wildfires across the continent.

Places like Brazil, Argentina, and Chile have faced some of their harshest droughts on record. Climate change is fanning these flames, along with weather-wreckers like El Niño that stir up long stretches of aridity—perfect for igniting fires.

The stunning Amazon Rainforest is under threat, crucially known as our planet's "lungs." On top of this, deforestation and changes to land use are only raising the stakes.

Lately, things have hit a boiling point with some catastrophic blazes roaring through areas such as the Pantanal, which crosses three different countries in South America.

These large devastating fires have destroyed huge areas of wetlands, and with it, the homes of countless animals. This in turn has put many different types of creatures and plants in great danger.

The impact of these droughts and fires is huge, making it hard for farms to operate, forcing people to leave their homes and way of life, and causing smoke-related health problems.

Droughts and wildfires in South America are closely linked and caused by a collection of factors, and now local and world bodies are fighting hard to find solutions to the problem.

Background on Climate Patterns in South America

South America has a wide variety of climate zones, and with it, weather patterns like El Niño. From the expansive greenery of the Amazon to the dry Atacama Desert and the cold, high Andes Mountains, each area has its own mix of ocean currents and air patterns that make up its regional weather.

The Amazon basin, which is hot and humid, with buckets of rain, making it a home for animals and plants not seen anywhere else on the planet. Down in the middle and south of the continent, like in Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay, the weather is hot in summer and cool in winter, and is considered subtropical.

Even further south, in parts of Chile and Argentina, they see noticeably cooler temperatures. At the southernmost point, such as Cape Horn, the weather can be frigid with extreme fluctuations, including variations in the length of days depending on the season.

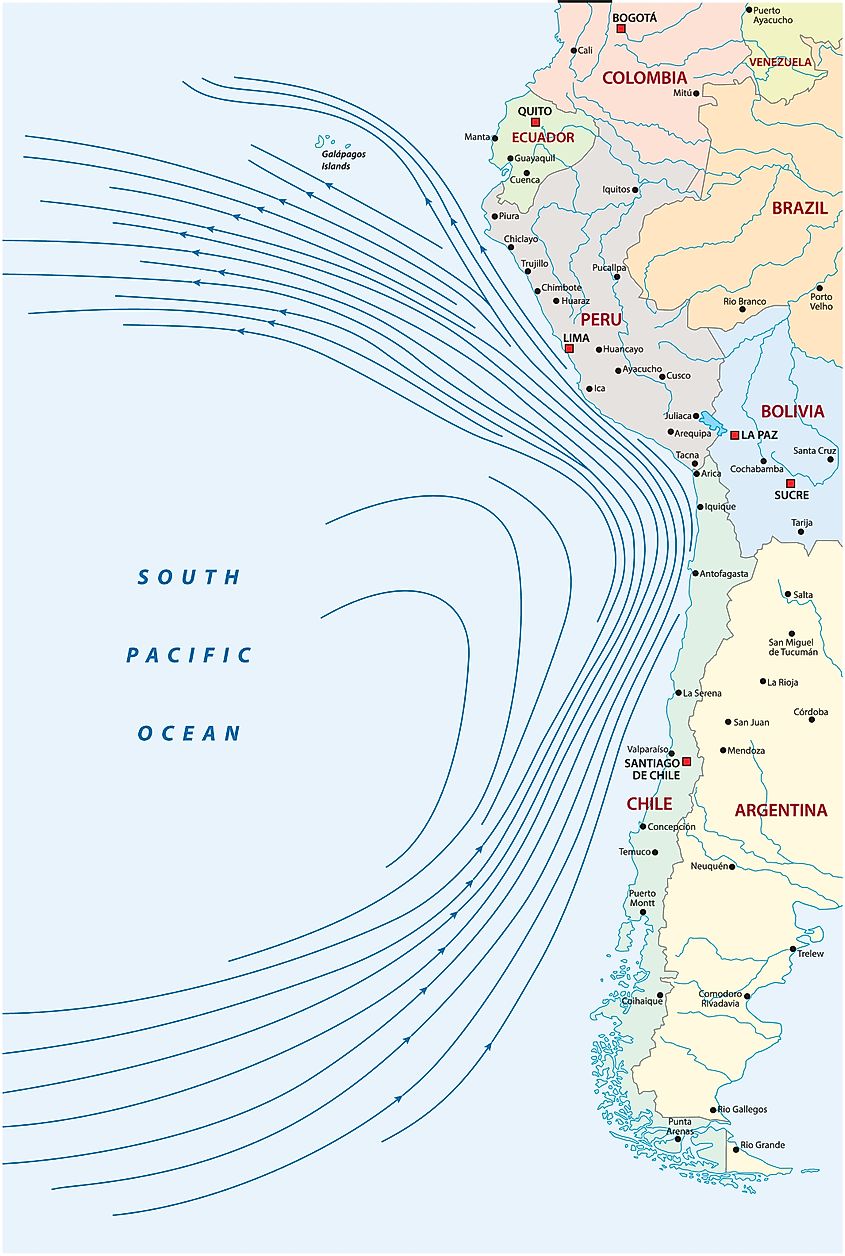

The Andes Mountain Range is an important part of weather all over South America. The range helps influence rainfall and regional temperatures. Another factor is cold ocean currents, like the Humboldt Current along the western coast. These currents help keep temperatures cooler and reduce rainfall by lowering the atmosphere's capacity to hold moisture, leading to lower humidity levels.

Historical records show that droughts in South America have come and gone, but the occurrence rate has risen. In the Amazon and Pantanal areas, a lack of rainfall is made worse by El Niño, which can make the Amazon both warmer and drier, leading to droughts and a high number of wildfires.

For example, between 2015 and 2016, El Niño was the main source of drought in the northern parts of South America. The resulting drought was particularly harsh on farming, water sources, and the natural world. It is not dissimilar to the recent fires in Pantanal, a huge wetland area, which experienced its worst dry spell in nearly 50 years. The dry spell helped lead to destructive fires harming much of the pristine wetland.

Environmental and Ecological Impacts

Brazilian Fires

Wildfires have a massive impact for all life in South America over the last decade. They cause harm to many plants and animals, impacting the incredible biodiversity the continent holds.

The Amazon Rainforest in particular is a crucial area for global biodiversity. According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), it has 9 percent of the world's mammals, 14 percent of the birds, 8 percent of amphibians, and 22 percent of plants with vascular tissues. When fires occur, they destroy their habitat, making it difficult for many species to adapt and survive and push others to extinction.

There is an interesting paradox with the Amazon's trees. Even though the expansive forests are full of lush greenery, the soil itself is not dense with nutrients. In the Amazon, the plants hold most of the important nutrients, not the soil, so when a fire rips through, that leads to a loss of those essential nutrients, making it harder for the forest to grow back.

While the nutrient composition of the Pantanal Wetlands differs, the damage is just as costly, both to the people and the very soul of the land where animals live and thrive. In 2020, the wetlands faced massive fires like never before, showing the long-term effects fires can have on the native land. About one-third of the wetlands were on fire. Extensive areas of the wetlands were burned, affecting a wide range of animals, including endangered species. This critical damage disrupts the natural balance and leads to a decrease in biodiversity. One species impacted by the fires is the Hyacinth Macaw, which saw significant portions of their habitat lost, putting this already endangered species at greater risk.

Over time, the damage from the fires can cause more problems like contaminated water and changes in water flow in the area. The Amazon creates "flying rivers," which are streams of vapor leading to other parts of South America. When forests in the Amazon are burned or cut down, these streams are disrupted. As you can imagine, this lack of vapor leads to lands that depend on that moisture teetering closer to drought.

Argentinean Fires

The fires in Argentina have been rough on the region's natural world, leaving a streak of devastation in areas including the grassy Pampas, faraway Patagonia, and the river-filled Paraná Delta. According to a 2020 report from the Argentine National Parks Administration, these blazes wiped out over 200,000 hectares of wetlands, home to animals like the capybara, marsh deer, and countless birds.

In places like the Pampas region of Argentina, the soil is rich with necessary components, like organic material and nutrients. But when wildfires come through, they burn away the top layer of the ground. This leads to both erosion and the loss of those nutrients. The Argentine Institute of Agricultural Technology (INTA) has found that fires can cut down soil fertility by as much as half, which can destroy a farmland’s productivity and the people’s livelihood.

Wildfires also have a big impact on water quality and the water cycle. With less vegetation, more water runs off into rivers and lakes, carrying more sediment along with it. The paper "Wetland Fire Assessment and Monitoring in the Paraná River Delta, Using Radar and Optical Data for Burnt Area Mapping" says this leads to a deterioration in water quality for both people and animals. For example, the Paraná River has become muddier due to wildfires in the nearby delta area due to the sediment.

Silvina M. Manrique and Judith Franco wrote in their article, "Native Forest and Climate Change — The Role of the Subtropical Forest, Potentials, and Threats," about how losing forests, like the Yungas and Andean woods, changes local weather patterns and lowers the forests' ability to store carbon.

It is no surprise, then, that reducing a forest’s ability to store carbon can have significant implications for climate regulation. This amplifies the effects of climate change and also reduces the variety of life, changes how water moves, and harms Indigenous people who rely on these forests to live and for their traditions.

Chilean Fires

Chile has been facing tough times with wildfires, especially in 2023. Wildfires spread out across approximately 500,000 hectares of land, far greater than the annual average area burned. The massive fires left dozens of people dead.

It seems odd at first, but part of the blame goes to the trees themselves. One cause of the increase in intense wildfires is non-native species, like pine and eucalyptus. A team led by Montana State University looked at the raging fires in Chile and identified several factors that contributed to these blazes.

The team found pine and eucalyptus tend to burn faster than the natural, local foliage. Because so many of these new trees have been planted, wildfires are escalating faster than they once did. This also makes it hard for various plants and animals to survive, reducing the biodiversity in these areas. Many animals and birds, which already struggle due to habitat fragmentation, are facing even more challenges now.

And it has profound impacts on soil health. Similar to other parts of South America, the soils in the affected regions of Chile lose essential nutrients during wildfires. This issue makes it harder for forests to replenish and for farms to produce food because the soil has lost its nutrients.

The Chilean fires have also increased soil erosion, which further depletes the land of its remaining nutrients and can lead to more severe flooding during the rainy season. According to a study "Forest Wildfires in Chile: Effects on Soil Degradation and Damage Mitigation" which looks at the effects of forest wildfires in Chile, these fires cause significant soil degradation. The soil degradation leads to more issues for the indigenous plants.

They also affect soil structure and hydrological properties. The high intensity of the fires leads to increased soil erosion, which is exacerbated by the loss of vegetation that normally helps to stabilize the soil. The Center for Climate And Resilience Research report Forest Fires in Chile: Causes, Impacts, and Resilience says the fires have changed the way water moves through the environment and how much water is available.

When trees are destroyed, it can disturb the natural water system, making it harder for the area to hold onto clean water. This problem does not just affect plants and animals but farming too, as less water is available for the locals.

Socioeconomic Consequences

South America has faced challenges due to wildfires and droughts, particularly in agricultural areas. These events hinder farmers' ability to grow crops and raise livestock, leading to reduced food production and increasing difficulties for people to afford the food they need.

According to the research in the article "Projected Increases in Magnitude and Socioeconomic Exposure of Global Droughts in 1.5 and 2 °C Warmer Climates," there is a potentially rough road ahead for tropical countries. It says that tropical countries like Brazil could see drought risks expand to 85 percent of the country at almost double the rate of past severe droughts.

The same study predicts that even with an ambitious goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C (around 2.7°F), about 70 to 75 countries worldwide countries will experience a situation where their entire population and economic output will be highly exposed to worsening droughts. An additional 0.5 degrees of warming would make this problem even worse, leading to a widespread socioeconomic vulnerability in 17 more countries.

In regions like the Amazon and the Pantanal, wildfires destroyed vast areas of farmland and natural habitats, exacerbating the economic burden. Local towns take a big hit too. When wildfires come along with dry spells, people have to pack up and move out, searching for places where they can be safe. Leaving home like that means many find themselves without jobs and facing tougher times than ever before.

In their analysis, the authors of "The Chile Challenge: Considerations for a Climate Finance Strategy in Chile" discuss the critical factors and strategies that Chile must consider to effectively finance its climate initiatives. They highlight the importance of integrating sustainable finance practices and developing robust climate policies to address environmental challenges.

They say that Chile's economic prosperity and advancement are intricately tied to climate change and, therefore, the wildfires that follow. By charting a course with low carbon emissions that is also sustainable, numerous benefits can be reaped towards a cleverly structured economy - one that is competitive yet inclusive while making efficient use of resources.

So, it is crucial that development and climate risk strategies not only coexist but also support each other. However, implementing this on a national level presents its own set of challenges and opportunities.

While the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) says while there have been stronger public health strategies when it comes to weather-based issues, there is still a lot of room for improvement.

Health issues are rampant in any country with wildfires. When the air fills with smoke from wildfires, it can cause irreversible damage and harm to people’s lungs. People who already have breathing issues, like asthma, will struggle even more in these conditions.

Numerous organizations like the American Lung Association and UCLA Health say wildfire smoke exposure is linked to a big increase in asthma-related emergency room visits and hospitalizations. People with chronic lung conditions such as COPD and bronchitis are also at higher risk of complications from smoke exposure.

Challenges to Predict, Stop, and Manage Wildfires

Stopping and handling wildfires in South America is no easy task, especially with climate change. The weather is getting harder to predict, with temperatures going up and dry periods lasting longer. These conditions make perfect conditions for more frequent and harder-to-fight wildfires.

For instance, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has found that in the last 50 years, droughts in South America have happened 30 percent more often and with more intensity. The increase in droughts goes hand in hand with more wildfires. Plus, traditional weather tools often can't keep up with the unpredictable impacts of El Niño on South America.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) says the Amazon, which has always been a massive carbon sink, is not absorbing as much CO2 because of the rate at which trees have been cut down. Not great news for both helping relegate world temperature and even worse for preventing fires. In fact, we have seen a loss of nearly a fifth of the Amazon's trees over the past half century, due to farming and timber cutting.

According to NASA, if there is not a change globally, temperatures could raise several more degrees by 2050. The paper “CO2 Physiological Effect Can Cause Rainfall Decrease As Strong As Large-Scale Deforestation In The Amazon” says with rising CO2 levels, rain levels could see significant drops, leading to longer fire seasons. The Pantanal faced some fierce fires in 2020, and if it gets any drier, it could become an even bigger fire hazard.

Governmental and International Response

In response, South American countries are getting serious about battling those fierce fires and tough droughts tearing through their lands. Take Brazil, which has invested in the National Institute for Space Research so they can keep a better eye on wildfires and swoop in faster when trouble sparks up. Plus, there is extra cash going to the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources, known as IBAMA, just for fighting future flames.

Argentina is not just sitting around either; it has a plan that brings different parts of the country together to put out fires, including the establishment of the National Fire Management Plan. Plus, it is investing in ways to know when a fire might start ahead of time and stop it before things get worse. Similarly, Chile has developed the National Fire Protection Policy, which includes strategies for fire prevention and restoration of affected areas.

It is not only about what each country does on its own - working together on a worldwide level is crucial. Groups like the United Nations (UN) and WMO have offered a helping hand by sharing technical advice. For example, the UN has mobilized resources to assist Brazil during severe wildfire outbreaks, and the WMO has provided early warning systems to predict and manage drought conditions.

There are also some pretty interesting international projects focused on tackling why these fiery nightmares happen in the first place. They share information between countries on how best to handle them, like the Global Fire Monitoring Center (GFFR) which helps send emergency teams when large-scale fires turn nasty.

The teamwork is regional too, as South American neighbors have promises like the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO) which make sure everyone works together while looking after the priceless value of the Amazon Rainforest.

All in all, when governments link up with international organizations, it is crucial to create joint plans to prevent wildfires and ensure a safe water supply.

Innovative Approaches and Research

Navigating the complex arena of an ever-shifting environment demands smart solutions and fresh research.

In South America, they are seeing some innovative tech step onto the scene, changing how countries watch over their natural resources. Satellites with high-quality cameras and live data collection can help keep a better eye on and predict fires.

For example, a team at MIT is using drones and tech that measures ground movements to collect nonstop information in difficult-to-reach places. This makes the forecasts of weather models and risk checks more precise.

Groups like the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) are working hard to come up with plans to deal with wildfires. They are trying to mix ways to adapt to the changing climate into how forests are looked after and support rules that make places stronger against disasters caused by the climate.

Even though it is really tough to predict, stop, and handle wildfires as the climate changes, new ideas and working together across countries provide hope for lessening the damage caused by these fires and making places more able to withstand them in the coming times.

These include integrating climate adaptation into forest management practices and promoting policies that enhance resilience against climate-induced disasters. While the challenges in preventing managing wildfires amid changing climate conditions are difficult at best, innovative approaches and international collaboration offer promising options.

Over the last decade, South America has been hit with extreme dry spells and massive wildfires. For the people who live there, and in fact all of us, it cannot be ignored.

Unpredictable weather is becoming the norm thanks to climate change, and curveballs like El Niño will make things increasingly uncertain. Countries like Brazil, Argentina, and Chile are perfect examples of countries in South America feeling the effects, with negative impacts on both nature and people's lives.

Places like the Amazon rainforest and Pantanal wetlands, home to vast amounts of plants and animals, have been severely impacted. This damage affects many aspects of life, including farming, water quality, and health. People have been hit hard, with some forced to leave their homes, struggling to find enough food, and more people falling into poverty.

To fight these issues, governments in the region have been improving their firefighting capabilities, establishing early warning systems, and creating detailed fire management plans. International groups like the UN and WMO have been crucial in providing technical assistance and funding.

By integrating climate change strategies with forest management and promoting sustainable land use, South America can better protect itself against wildfires and droughts. This is vital for preserving important natural resources and ensuring people can live well and healthy.

Works Cited

Amazon Cooperation Treaty.” OTCA, otca.org/en/project/amazon-cooperation-treaty/.

“Another Climate Record: Extreme Heat, Hurricanes, Droughts Ravage Latin America and Caribbean | UN News.” UN News, 8 May 2024, news.un.org/en/story/2024/05/1149516.

“Causes, Consequences, and Prevention of Wildfires in Chile | Columbia Global Centers.” Globalcenters.columbia.edu, globalcenters.columbia.edu/content/causes-consequences-and-prevention-wildfires-chile.

Connell, Jemima, et al. “Fire, Drought and Flooding Rains: The Effect of Climatic Extremes on Bird Species’ Responses to Time since Fire.” Diversity and Distributions, vol. 28, no. 3, 2022, pp. 417-38. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/48650465.

Dacre, H. F., et al. “Chilean Wildfires: Probabilistic Prediction, Emergency Response, and Public Communication.” Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, vol. 99, no. 11, 2018, pp. 2259-74. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26639225.

Del Valle, Héctor, et al. "Wetland Fire Assessment and Monitoring in the Paraná River Delta, Using Radar and Optical Data for Burnt Area Mapping." Fire, vol. 5, no. 6, 2022, p. 190. MDPI, https://doi.org/10.3390/fire5060190.

Drake, Paul W, and John J Johnson. “Chile | History, Map, Flag, Population, & Facts.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 25 June 2019, www.britannica.com/place/Chile.

“El Niño and Climate Change Impacts Slam Latin America and Caribbean in 2023.” World Meteorological Organization, 7 May 2024, wmo.int/news/media-centre/el-nino-and-climate-change-impacts-slam-latin-america-and-caribbean-2023.

Ferreira, G. W. d. S., et al. “Assessment of Precipitation and Hydrological Droughts in South America through Statistically Downscaled CMIP6 Projections.” Climate, vol. 11, no. 8, 2023, p. 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli11080166.

“Fires in Argentina: Wildfires in the Paraná Delta Threaten Lives - Latin America News Dispatch.” Latindispatch.com, 22 Nov. 2020, latindispatch.com/2020/11/22/fires-in-argentina-wildfires-in-the-parana-delta-threaten-lives/.

“Forest Fires in Chile: Causes, Impacts and Resilience | Center for Climate and Resilience Research - CR2.” CR2, 28 Jan. 2021, www.cr2.cl/eng/forest-fires-in-chile-causes-impacts-and-resilience/.

GFMCadmin. “Regional South America Wildland Fire Network - GFMC.” GFMC, gfmc.online/GlobalNetworks/SouthAmerica/SouthAmerica.html.

Gu, L., et al. “Projected Increases in Magnitude and Socioeconomic Exposure of Global Droughts in 1.5 and 2 °C Warmer Climates.” Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., vol. 24, 2020, pp. 451-472, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-24-451-2020.

Hansen, Kathryn. “Fires Scar the Chilean Landscape.” Earthobservatory.nasa.gov, 17 Feb. 2023, earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/150994/fires-scar-the-chilean-landscape.

Henrique, Bruno, et al. “Wildfires Jeopardise Habitats of Hyacinth Macaw (Anodorhynchus Hyacinthinus), a Flagship Species for the Conservation of the Brazilian Pantanal.” Wetlands, vol. 43, no. 5, 5 May 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-023-01691-6.

Keenan, Rodney J. “Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation in Forest Management: A Review.” Annals of Forest Science, vol. 72, no. 2, 14 Jan. 2015, pp. 145-167, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-014-0446-5.

Libonati, Renata, et al. “Rescue Brazil’s Burning Pantanal Wetlands.” Nature, vol. 588, no. 7837, 1 Dec. 2020, pp. 217-219, www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-03464-1, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03464-1.

Manrique, Silvina M., and Judith Franco. "Native Forest and Climate Change — The Role of the Subtropical Forest, Potentials, and Threats." IntechOpen, 30 Mar. 2016, www.intechopen.com/chapters/71867.

Martins, Luciano. “Brazil | History, Map, Culture, Population, & Facts.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 11 Mar. 2019, www.britannica.com/place/Brazil.

Matus, Francisco, et al. Forest Wildfires in Chile: Effects on Soil Degradation and Damage Mitigation. 27 June 2023, https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202306.1802.v1.

McWethy, D. B., et al. “Landscape Drivers of Recent Fire Activity (2001-2017) in South-Central Chile.” PLOS ONE, vol. 13, no. 8, 2018, e0201195, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201195.

NOAA Research. “Deforestation, Warming Flip Part of Amazon Forest from Carbon Sink to Source.” NOAA Research, 14 July 2021, research.noaa.gov/2021/07/14/deforestation-warming-flip-part-of-amazon-forest-from-carbon-sink-to-source/.

“Q&A: Climate Grand Challenges Finalists on Using Data and Science to Forecast Climate-Related Risk.” MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 7 Apr. 2022, news.mit.edu/2022/using-data-and-science-forecast-climate-related-risk-grand-challenges-0407.

“South America Ravaged by Unprecedented Drought and Fires.” Phys.org, phys.org/news/2020-10-south-america-ravaged-unprecedented-drought.html.

Spadaro, Paola Andrea. “Climate Change, Environmental Terrorism, Eco-Terrorism and Emerging Threats.” Journal of Strategic Security, vol. 13, no. 4, 2020, pp. 58-80. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26965518.

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “Pantanal | Floodplain, South America.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 9 July 2015, www.britannica.com/place/Pantanal.

UCLA Health. "Wildfire Smoke Dangerous to Those with Lung Conditions." UCLA Health, 16 Sept. 2022, www.uclahealth.org/news/article/wildfire-smoke-dangerous-to-those-with-lung-conditions.

“United Nations. “Mega-Drought, Glacier Melt, and Deforestation Plague Latin America and the Caribbean.” UN News, 22 July 2022, news.un.org/en/story/2022/07/1123032.

Úbeda, Xavier, and Pablo Sarricolea. "Wildfires in Chile: A Review." Global and Planetary Change, vol. 146, 2016, pp. 152-161, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2016.10.004.

Villagra, P., and Paula, S. “Wildfire Management in Chile: Increasing Risks Call for More Resilient Communities.” Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, vol. 63, no. 3, 2021, pp. 4-14, https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2021.1898891.

World Wildlife Fund. “5 Interesting Facts about the Pantanal, the World’s Largest Tropical Wetland.” World Wildlife Fund, www.worldwildlife.org/stories/5-interesting-facts-about-the-pantanal-the-world-s-largest-tropical-wetland#:~:text=At%20more%20than%2042%20million.

World Wildlife Fund. “The Amazon in Crisis: Forest Loss Threatens the Region and the Planet | Stories | WWF.” World Wildlife Fund, 8 Nov. 2022, https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/the-amazon-in-crisis-forest-loss-threatens-the-region-and-the-planet.

“Managing Wildfires in the Context of Climate Change." OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, https://www.oecd.org/climate-change/wildfires/.

“Environment, U. N. “Managing Wildfires.” UNEP - UN Environment Programme, 29 Mar. 2022, www.unep.org/explore-topics/forests/what-we-do/managing-wildfires.