Spotlight On The Royal Bengal Tiger: An Ageless Chronicle Of The Soul Of India

“In the first decade of the 20th century, the most prolific serial killer of human life the world has ever seen stalked the foothills of the Himalayas……. A serial killer that happened to be a Royal Bengal tiger."

...............No Beast So Fierce, Dane Huckelbridge

More than two centuries after the killing of this “man-eater” called the Champawat Tigress by the celebrated hunter Jim Corbett, an acclaimed American author Dane Huckelbridge retells her story, a story that is very different from those told in the past and by Corbett himself. A story that endeavors to investigate the “making of the man-eater.”

In this article, we present you with a comprehensive history of the Royal Bengal tiger. We attempt to travel through time with the tiger to understand how this magnificent beast braved the test of ever-changing landscapes and a rapidly mutating environment to emerge as the wildlife guardian of India. We explore how, despite numerous efforts to malign its reputation with a "man-eater" tag, the tiger succeeded in captivating the hearts of millions in the world's largest democracy.

On this timeless journey of the Royal Bengal tiger, we have with us Dane Huckelbridge and India’s leading wildlife conservationist Dr. Anish Andheria to provide us an insightful view of the life of the tiger as it unfolded during the colonial and post-colonial times in India respectively.

When It Was The Time Of The Tigers

Before the sahibs from the "empire on which the sun never sets” arrived in India, the world of the Royal Bengal tiger was vastly different, unrecognizable from its current state.

In his highly illustrious book entitled “India’s Wildlife History,” Mahesh Rangarajan paints the picture of India’s wilds as it was before the ravages of colonialism left it permanently scarred and battered.

Knowledge about the state of wildlife in the pre-Mughal era India is scarce and primarily comes from mythological tales, ancient Sanskrit texts, traveler accounts, and archeological remains. If the information on ancient Indian wildscape documented in Rangarajan's book is summarised, it can help put a picture of the primitive wilderness into a frame.

As the picture emerges, it can be seen that from about 1,500 years back when Valmiki's Ramayana assumed the modern shape that we read today, and until the Mughals invaded India, the aranya or the forest was both feared and revered by early inhabitants of the land now called India. Dense forests teeming with life covered enormous swathes of land at a stretch. Hunting was always prevalent and popular and tales of Indian maharajas (Indian kings) from this period almost always mentioned their hunting skills as symbols of their bravery and prowess. Often, liaisons were formed between forest-fringe dwellers and the king's men to organize hunt parties when the king expressed his desire to go on a royal hunt. Wildlife was also hunted for meat and other body parts by the locals living in and around forests. However, it is quite understandable that given the low human populations, poor accessibility to dense forests, and old-fashioned infrastructure and weapons, the rate of hunting of wildlife was definitely a minuscule display of what is possible today.

Under such sound ecological conditions where habitats were both secure and providing, the Bengal tiger ruled. It ruled as it would never rule again in the future. The tiger was then the desire of the maharaja. It held the position of utmost importance and reverence as its killing gave a bravery badge to its killer. The tiger was then truly the 'king of the jungle' whose position could only be usurped by another king, a human one albeit.

Indeed, it was "the time of the tigers."

The Tiger Vs The Mughals

The tiger continued to bask in glory as the foreign invaders, the Mughals, raided the land, conquered Hindu kingdoms, and settled down to rule India from the 16th to the 18th centuries. Fortunately for us, the Mughals recorded their observations and activities in great detail and a much transparent vision of the Royal Bengal tiger and its homeland emerged before us from this time onwards.

Back then, tigers were still numerous and sightings of these predators near the premier cities of Delhi and Agra were not uncommon. The Mughals also reveled in tiger hunts. Accounts mention Emperor Jahangir slaying 86 tigers during his lifetime. Elaborate hunts organized by the Mughals often came with political connotations. Wild meat was highly prized.

Although the Mughals hunted tigers and other wildlife, Mughal-era India was still replete with forests that had abundant wildlife populations. Hunting at that time was never indiscriminate. Deforestation rates were not entirely non-existent but low.

Enter The Tiger Slayers: Beginning Of The Near End

Everything changed when the British came.

The Royal Bengal tiger now had an unequal enemy, one that held so much power over it that its nature-gifted predatory abilities were no match in front of British bullets and lust for its blood.

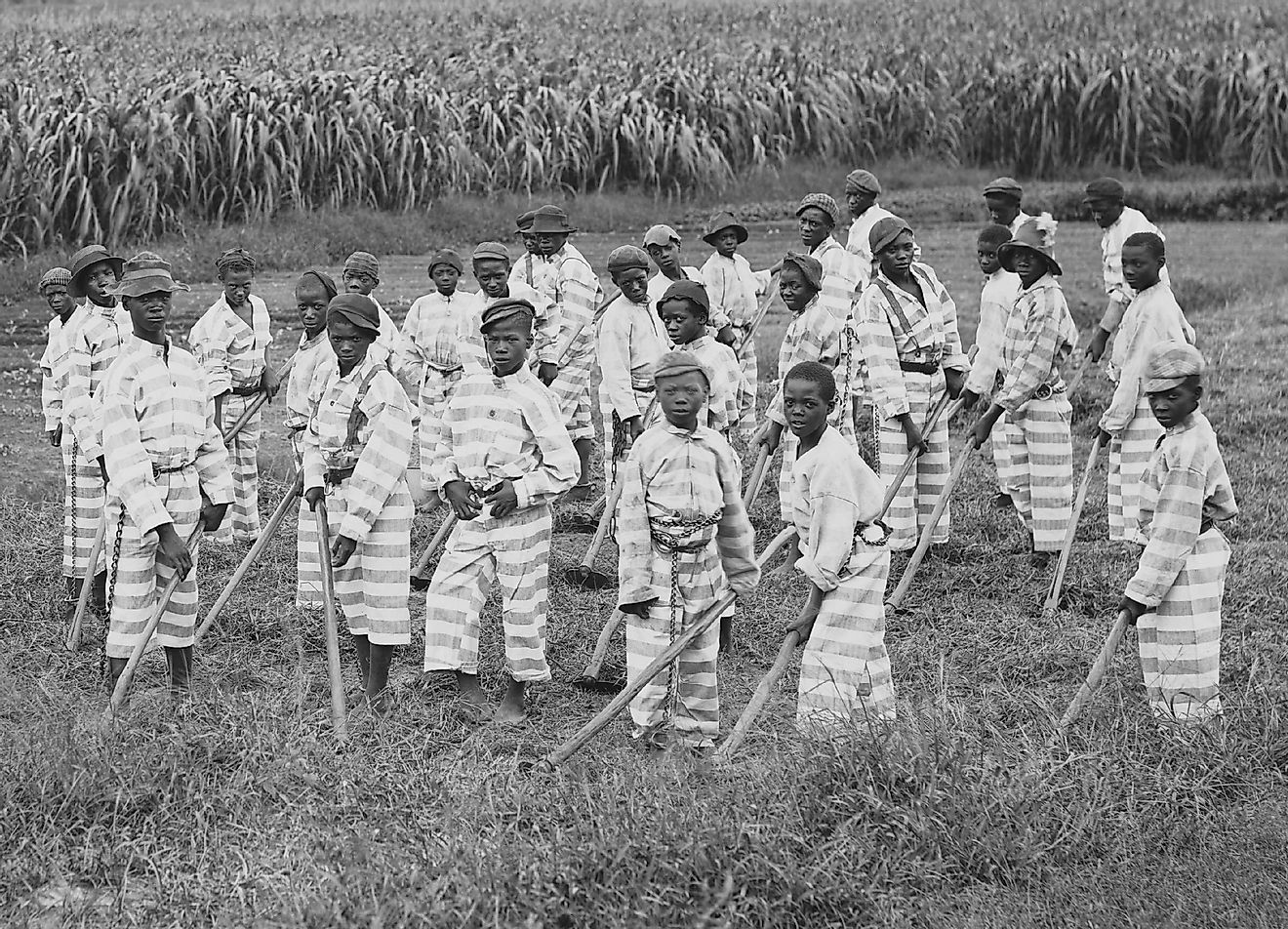

For the first time in history in the country came a ruler that killed tigers to exterminate the species completely.

The hatred of the colonizers for flesh-eating beasts was not new. In their country back in the British Isles, they had already perfected their skills in finishing off the wolf, the primary predator there.

Soon after establishing their rule in India, they started offering handsome rewards to those who were ready to execute their killing spree. Larger rewards were given off for killing tigresses, the bearer of cubs.

To please the new rulers and gain their favor, many Indian kings also now joined the gory sport of tiger hunting in its new avatar.

Protective hunting also developed during this time where hunters from the white community went to villages supposedly terrorized by "man-eating" tigers to kill the beast and attain "godhood" in the eyes of the "weak" natives.

As the massacre continued and the forests were cleared off tigers, it served the economic interest of the new rulers who had now predator-free forests to exploit to the fullest extent. The remaining tigers now got cornered to smaller and smaller patches of forest.

Human-tiger encounters, however, instead of abating, increased manifold. Devoid of stable habitats and lack of sufficient natural prey that instead landed on the plates of the new rulers, the tigers were left with no choice but to enter human-dominated areas where hunting of cattle and sometimes even humans became their last resort to survival.

It was under these dire circumstances that the story of the Champawat tigress who allegedly killed over 400 humans, came into being.

A Fearless Fighter Born In An Unfortunate Time

Perhaps no member of the tiger species has inspired such awe and fear as the legendary Champawat tigress of 20th century India. Her name finds mention in the Guinness Book of World Records as a tiger responsible for the highest number of human deaths!

Convicted for the death of at least 435 people, she became the ‘apple of the eye’ of Jim Corbett, a hunter who shot to fame by executing the impossible. He hunted down the indomitable Champawat in 1907, bringing an end to her ‘reign of terror.’ In doing so, he saved hundreds of ‘helpless, native Indian villagers from a gruesome death in the jaws of the vicious tigress.

At least that is the picture of Champawat and her hunter that we have been trained to imagine over all these years and across generations.

Now, in the 21st century, Dane Huckelbridge decided to ravage through the pages of history to bring forth a more accurate picture of the happenings that led to the untimely death of the Champawat tigress in British India.

Responding to World Atlas’s question about what prompted him to write "No Beast So Fierce, Dane answers:

“I've always had an interest in apex predators in general, and my original idea was to write a broader book about such predators that turn to human predation, with one chapter focused on the Champawat Tiger. My editor thought that might be a little too broad, however, and later on, he came up with the idea of just focusing on the one tiger, for a more precise and clear message. I think in general, when it comes to man-eating predators, the story is usually the same: environmental destruction and loss of habitat and prey species. But the story of the Champawat Tiger teaches this lesson very well on its own.”

Indeed, to truly experience what this unfortunate tigress went through to earn the abhorred title of a man-eater, we must first understand the era in which she was born - a time when the human rulers of the land where she lived had only one aim - to remove all traces of members of her kind. Dane explains in detail the extreme survival challenges confronting the Bengal Tiger when Jim Corbett set out to hunt his first “man-eater.”

“In the early years of the 1900s, there were probably 100,000 wild tigers in the world, with three-quarters of those almost certainly in India. But the steep decline of wild tigers had already begun, even though people didn't realize it at the time. The true extermination of wild tigers would occur from the late 1800s up until the mid-1900s.”

And the Champawat was just one of the earliest victims of this act of butchery. In fact, upon silencing her, Corbett mentions how he discovered that the upper and lower canine teeth on the right side of her jaw were broken — the result of a past gunshot wound. Corbett concluded that it is these broken canines that prevented her from killing her natural prey and resort to humans, a relatively easy catch for a tiger.

Dane also explains why the man-eating problem was more a product of British policies than nature's ways gone weird.

“In the pre-colonial era, tigers were protected as "royal game" in much of India, and hunting tigers was a ritualistic activity reserved for the noble elite. Village populations would hunt a tiger if it became problematic, but large-scale tiger hunting of the sort seen during the colonial era was rare. At that time, due to the availability of habitat and prey, there was less pressure on tigers to find food and territory, and thus less human-tiger conflict. There certainly are accounts of human predation going back to the pre-colonial and early colonial era, but the real explosion in man-eating, at least in the northwest region where Corbett lived, seemed to have begun when the species was most threatened, in the 1910s and 1920s, following a few decades of mass-hunting and timber felling by the colonial government. Prior to the Champawat Tiger, human-tiger conflict was relatively rare in Kumaon, it was one of the first incidents Corbett had encountered. But in the decades that followed, Jim Corbett would be called on time and time again to hunt problematic leopards and tigers. Essentially, the predators had run out of habitat and food, and out of desperation, had begun hunting people. Something very similar happened to the last remnant populations of wolves in Europe in the 1700s and 1800s. The more cornered they were, the more aggressive they became.”

People Or Puppets?

Another thing that strikes us most about the Champawat tigress is the extreme disgust with which she was treated by the people of her own - the natives of the land. Jim Corbett recounts in his book how the village men wanted to carry the corpse of the tigress around the village to ensure their wives and children that their 'dreaded enemy' had been put to silence forever. He also narrates how the entire village watched in awe as he skinned and dismembered the tigress - a truly ghastly sight - and later held a grand feast and dance in honor of their savior, Jim Corbett.

However, when we delve into history, both ancient and recent, we find that it always glorifies the role of the Indian culture in preserving and protecting the country's flora and fauna. In fact, Dane mentions in his book about how the Tharu community of the Himalayan foothills, the primary victim to the predation by Champawat, revered tigers as benevolent guardians and protectors of the forest on which they depended for their livelihood. Even today, the belief that tiger attacks on humans are a form of divine punishment persists in this community. What then changed during British rule that these very people turned thirsty for the blood of their "protector?" Were they under a more powerful influence that forced them to suspend their cultural memory temporarily? Dane has an answer.

"I think rural populations that negotiate their existence alongside tigers have always viewed the animals with respect and awe, and when appropriate, even fear. But for any farmer reliant on grain crops to feed their family, having tigers in the area to keep deer and wild pig populations in check was tremendously beneficial. The very real threat of having crops destroyed by an overpopulation of deer was much more troubling than the very rare chance that a tiger would attack a human. Also, in pre-colonial times, rural populations had far better means to protect themselves in the event that a tiger did turn problematic. Hunting and the ownership of weapons were largely banned in the latter part of the colonial era, leaving many villages unable to defend themselves in the event of a tiger attack. That, coupled with bounties placed on tigers and the arrival of increasingly aggressive tigers due to habitat destruction almost certainly did help to vilify tigers. But even today, when I speak to the Tharu who live in areas where human-tiger conflict still occurs, the farmers generally fear aggressive elephants and crop-eating wild pigs far more than tigers. The odds of being attacked by a tiger are just too small, while the chances of having a bull elephant harass their house, or having a herd of wild pigs eat their crops, is quite high. Seeing a tiger is so rare, it's actually considered good luck in most cases."

While it becomes quite clear that the natives were definitely mere puppets in the hands of the British Raj, what about the hunters who acted on behalf of the rulers? As we know, Jim Corbett is today praised for his role in the conservation of Indian wildlife, one of the firsts to usher in the welcome change that valued the worth of wildlife and focussed on the need to conserve. However, one cannot deny that he was also a prolific hunter in the earlier years of his life who climbed the social ladder in British society through his successful "man-eater" hunting expeditions. So, the question that arises is whether he was truly a hero, a selfless figure who saved innocent villagers from the jaws of death or was he just another perpetrator of Eurocentric paternalism?

Dane shares his views on this legendary hunter turned conservationist:

"Jim Corbett was a complex and tremendously brave man with a profound love for India and a very strong sense of duty. But having grown up within the colonial system, he was certainly conflicted at times about what that sense of duty meant. I don't think Corbett was simply a tool used by the British per se, because he was very much a part of that same colonial system, and invested in it. However, I think he definitely had the best interests of the local Kumaoni population in mind as well. He truly did want to save his fellow Kumaonis from tiger attacks; some plaudits did come with killing such a tiger, and while that may have been a consideration, I don't think it was his primary motivation. But while Corbett was in many ways ahead of his time, he was also a product of his time, and I don't think he realized how destructive colonial forestry and hunting policies were until later in his life. But when that revelation did hit home, he did everything in his power to protect tigers and change government policies. Had he known as a young man that tigers would be driven to the brink of extinction, I doubt he would have ever hunted them at all except in extreme cases, or have assisted people who did."

From the above discussion, it becomes clear that the story of the Champawat tigress is more than just her story. It is the chronicle of a country and her people under troubled times going through profound changes under foreign administration of a power that wanted to extract all that was possible to fill in their coffers back in their homeland, Britain.

A Change In Fate For India, But Not Her Tiger

Although India earned her independence from British colonial rule in 1947, it did not bring any sign of relief for her Royal Bengal tigers who continued to be heavily exploited, a result of colonial hangover that showed no signs of disappearing anytime soon.

As per National Geographic's "A Concise History of Tiger Hunting in India," the killing of tigers escalated after 1947. Now, worse than ever, hunting became a sport free for all. Hunters from across the world were lured to the country by travel agencies offering the best trophies possible. The Indian Maharajas who were yet to be stripped of their titles now set up staggering hunting records. Since trophy hunting selects for the biggest and the most impressive individuals for hunting, India's tiger gene pool became weaker than ever before.

The demand for cat skin coats for the Western-world models and Hollywood starlets flaunting them further fuelled the demand for tiger skins from India. In the 1950s, a tiger felt was valued at $50 in India, a massive sum at that time.

The Tiger Finds A Savior In The Iron Lady Of India

The Royal Bengal tiger's fate drastically changed for the better when India got her first female Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, also popularly known as "the Iron Lady of India" in 1966. Living up to her name, she implemented her "iron will" to stop any further exploitation of India's tigers.

In 1969, upon recommendations by the World Conservation Union, and amid much hue and cry from the trophy hunting industry that was plundering $4 million a year by stealing the lives of India's tigers, the Indian Board of Wildlife asked states to ban tiger hunting for five years.

In 1972, Gandhi set up a group of specialists chaired by conservationist Karan Singh to assess the situation further. This task force submitted its report, often referred to as the blueprint of Project Tiger, in August 1972.

In 1973, Project Tiger, the world’s most comprehensive tiger conservation program, was conceived for six years from April 1973 to March 1979 (and later extended) to protect and conserve India's tiger population for future generations. Initially, nine tiger reserves were set up - Manas, Palamau, Simlipal, Corbett, Ranthambhore, Kanha, Melghat, and the Sundarbans. The number of tiger reserves grew to 15 by the early 1980s.

Now, things looked to be on the brighter side for the tiger. After centuries of exploitation and neglect, the tiger found a friend in India's new conservation strategies. But the struggle was far from over.

Unfortunately for the tiger, life is never a bed of roses, and soon the newfound hope faded away. When Indira Gandhi was assassinated in 1984, tiger numbers were considered to be growing steadily. However, by the late 1980s, tigers started disappearing again.

India’s Tigers At The Turn Of The 20th Century

Joining The Dots, a report by the Tiger Task Force set up in 2005 by the Indian Ministry of Environment and Forests to review the management of the country's tiger reserves, gives us an insightful view of tiger conservation in India at the turn of the 20th century.

And the picture painted by the report was really concerning.

The Bengal tiger appeared to be doomed once more. Retaliatory killings, poaching, habitat destruction, and general apathy towards the tigers caused the tiger population to plummet once again. The report states how a lack of political will, poor coordination between central and state governments, economic interests, faulty relocation policies, and a disconnect between tiger conservationists and the general public, acted in cohesion to push tigers to the brink.

Another major shock jolted the nation in December 2004 when it came to light that the Sariska Tiger Reserve had lost all its tigers. The Wildlife Institute of India (WII) reported in March 2005 that no trace of tiger remained in the reserve that initially claimed to host an estimated population of 24 to 25 tigers. What happened then?

A report by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) revealed that since July 2002, Sariska's tigers had been brutally poached one after the other.

The secrecy behind the killings and the mismanagement of the reserve roared aloud about the dismal state of India's national animal and questioned the very effectiveness of Project Tiger.

There were lessons to be learned from this tragedy and time was limited. Urgent action and effective, novel strategies to save India's national animal were the need of the day.

As one of the earliest steps in this direction, and on the recommendation of the Tiger Task Force, the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) was founded in December 2005. This body was constituted by the then Indian Prime Minister and tasked with the reorganized management of Project Tiger and India's Tiger Reserves.

The Rise To Stardom In 21st Century India

Thus, in the company of the NTCA, and after overcoming monstrous challenges, India's tigers survived into the rapidly evolving 21st-century world.

To know about the world of the tiger in India in the present era, World Atlas interviewed Dr. Anish Andheria, a large carnivore specialist with deep knowledge of predator-prey relationships. President and CEO of Wildlife Conservation Trust, India, Dr. Andheria is also a member of the Maharashtra State Board of Wildlife, and the NTCA.

"In the first decade of the 21st century, tiger conservation in India was riddled with a multitude of hurdles and threats," says Dr. Andheria.

Talking about these challenges, he mentions:

"Until 2006, in the absence of reliable data on tiger population size, we did not have accurate figures to know exactly how many tigers we were protecting and how many had been lost. There was also a great disparity in the protection protocols followed across different tiger reserves of India. Although buffer zones existed, they were not notified. Poaching was rampant in areas outside the Protected Areas and in several parks, even inside. Most of the easily accessible wild tigers of other countries had fallen victim to poaching and now, the poaching mafia turned their attention to India. As comprehensive compensation payment policies for crop and livestock depredation by wildlife were lacking, the forest-fringe dwellers would often turn against the tigers and other wildlife, and retaliatory killings were not uncommon. Prey populations were also inadequate in many tiger reserves and adjoining areas."

From the above account by Dr. Andheria, it becomes clear that conserving the tiger was anything but easy for the 21st-century conservationists. The 2006 All India Population Estimation exercise that used a much more robust method based on camera trapping, the most accurate one till then, presented the Royal Bengal tiger population as 1,411. The figure was a shudder down the pride of a country that had designated the tiger as one of her national symbols.

However, the determination of the nation was stronger now than ever before. Media became flooded with "Figure 1,411." There was uproar from all corners of India to save the tiger. Media campaigns were conducted to raise public voice on this issue. The government and conservationists also became more active than ever before.

The tiger was now a star in India.

Under such circumstances, tiger protection improved and the population exhibited a steady growth.

Consecutive All India Estimation Programmes conducted in 2010, 2014, and 2018 confirmed an increase in tiger numbers to 1,706, 2,226, and 2,967 respectively. India was now flooded with applause for its success.

But what were the exact factors that influenced the rise in tiger population? Once more, we turn to Dr. Andheria for a response.

"A great number of measures were adopted and implemented to ensure success in tiger conservation," says Dr. Andheria.

"Management Effectiveness Evaluation (MEE) was adopted by the NTCA in 2010-11 to assess the management system of tiger reserves in India. NGOs active in conservation were invited to actively participate in tiger conservation. Village Eco-development Committees were rejuvenated. The tiger habitat under analysis was increased with every estimation cycle. Protection was beefed up in the tiger reserves. Voluntary relocation programs funded by the State and the NTCA were implemented. Water conservation measures in tiger habitats were implemented. All tiger deaths began to be treated as "poaching" by the NTCA unless otherwise proved. This helped keep the management team of the tiger reserves ever-vigilant. New forest staff ranging from guards to IFS officers were recruited at a more steady pace to create a younger, more dynamic workforce. STPF or Special Tiger Protection Force was set up by some states on the recommendation of the NTCA to focus on the protection of tigers. These above factors acted in cohesion to stabilize and raise tiger populations in the country. However, it must also be remembered that there was a disparity in the performance of states across the country," informs Dr. Andheria.

Yet, The Struggle Was Far From Over

Despite its star status, threats to the tiger, however, never got diluted. While better protection and management reduced the poaching incidents significantly, a new kind of menace loomed over India's tigers - a tug-of-war between the tiger and its own people...where the loss of the former was imminent without a change in the attitude of the latter.

"Indian culture has always been pro-environment. Animals including tigers are often revered or worshipped by the people. But the people's perception of tigers or their prey as threats to their livelihood arises when they do not receive proper communication from the concerned authorities and compensation for their losses. Such circumstances create the perfect battleground for human-tiger encounters. People are not the problem, but inadequate and counterproductive policies are," says Dr. Andheria.

And just like Tigress Champawat of the 20th century, the killing of Tigress T1 (popularly known as Avni meaning "Earth") of the 21st century also teaches us a lesson in the new era about how tigers are still vulnerable to the human whim.

Tigress T1: Champwat Of The New Century?

On November 3, 2018, a tigress named T1, popularly known as Avni from Yavatmal, Maharashtra, was unceremoniously killed by Asghar Ali Khan, son of independent hunter Nawab Shafath Ali Khan. Held responsible for the death of 13 people between June 2016 and August 2018, Tigress T1, was on the target of the forest department for long. The news of her death created a furor across India. Tiger lovers ranging from members of the public to the then Women and Child Development Minister of India and noted animal activist Maneka Gandhi lashed out at the Maharashtra Government claiming T1's death as nothing short of a "ghastly murder."

So, why was there such a hue and cry upon the death of a tiger that was proven to prey on humans? Was her death justified?

Dr. Andheria agrees that killing of tigers that get repeatedly involved in negative interactions with humans often becomes a necessary evil, however, he also mentions that Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) must be followed in achieving this goal.

In the case of Tigress T1, they were not. Concerns were raised by many including Gandhi that T1's life could have been spared if she was tranquilized, captured, and quarantined following standard protocols. The involvement of the team of private shooters in killing T1 was also heavily criticized by the people of India.

More importantly, a committee appointed by the Maharashtra state government to investigate the death of the tigress found several flaws in the procedure harnessed to capture her or put her down. The committee determined that Asghar Ali Khan was guilty of shooting the tigress without being authorized to do so. Details of the investigation by the committee found in this news report here exhibits how T1's death was the product of utter mismanagement and chaos. Experts also mention that several human victims of T1 and possibly she could have been saved had early interventions been made assisted by clear-cut policies and their judicious implementation.

And so, just like Tigress Champawat who fell prey to grisly British policies in 20th century India, the controversial killing of Tigress T1 represents the inadequacies of the tiger protection policies in the 21st century in protecting the majestic predator. And experts claim that more cases like hers are to follow as tiger populations grow amidst an ever-growing number of Indians.

Summing Up The Existing Threats

Thus, the case of Tigress T1 wakes us up to the fact that tigers in India continue to be on the brink. As old threats fade away, new ones emerge strong. Dr. Andheria sums up some of the biggest threats facing India's tigers in the present day:

"So, while India has enough habitat to support a growing tiger population of up to 10,000 tigers, the lack of sufficient wild prey and social acceptance by local communities are the biggest hurdles in this direction," he says. "Retaliatory killings of tigers by people through poisoning or electric shocks using illegally tapped overhead transmission lines threaten the species more than ever before. Also, the fragmentation of viable tiger corridors due to the construction of linear infrastructure through such areas, habitat loss, and forest degradation threaten the healthy intermixing of populations."

India Needs Her Tigers

In the end, we all need to discuss a very basic question. Why do we need tigers?

"There is charisma in the name and form of the tiger. Even somebody who has never seen the tiger is awed by the mention of the species. It is this universal appeal of the tiger that has been harnessed to protect habitats where they live which, in turn, has saved many other species sharing the habitat from exploitation. It has also preserved the natural resources like rivers that arise from forests where tigers dwell," explains Dr. Andheria.

"Tiger also greatly benefits the economy through tourism," continues Dr. Andheria. "Such kind of tourism attracts both domestic and foreign visitors to India and supports the livelihood of countless families in rural India. However, there is an even greater scope to explore the true potential of tiger tourism in India."

He also explains how tigers benefit the village economy by maintaining the balance of nature. As an apex predator, the species keeps the herbivore population in check, which reduces crop depredation by wild herbivores.

In the case of India that is home to over 70% of the global tiger population, the national animal also means more than just an endangered species in need of protection.

"The tiger is synonymous with India. It is India's symbol of pride," says Dr. Andheria. "And we must save it for future generations," he concludes.