Wolves And Humans Giving A Tough Time To Wyoming’s Mountain Lions

There was a time when humanity's intrusion into wild landscapes was minimal - the ecological balance was undisturbed, and pumas and wolves both thrived in North America. Human disturbance, especially indiscriminate hunting, however, completely exterminated wolves, an apex predator, from America's oldest national park - the Yellowstone National Park, by the 1920s. Several decades later, an effort was made to correct the 'human error' and manage the rising elk population by reintroducing wolves to the park in 1995. But the results were, in many ways, unexpected- as evident in a recently published scientific study exhibiting the effects of reintroduced wolves on the puma population in the southern Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) in northwest Wyoming. This article explores the current status of pumas and the implications of the scientific study in puma and wolf population management in the study area. Dr. Mark Elbroch, Panthera’s Puma Program Director, provides an insight into the study in an interview with World Atlas.

Pumas On The Radar

Pumas have the most extensive geographic range of any native terrestrial mammal in the Western Hemisphere. These animals are known to inhabit a wide range of habitats including every forest type, open steppe grasslands, and even montane deserts across their range. However, despite their distribution across 28 countries from southern Alaska to the southern tip of Chile, puma populations are declining overall. Multiple factors including habitat loss and fragmentation, overhunting, human-puma-conflicts, road mortality, and disease are held responsible for the disappearing pumas.

With pressures on puma populations increasing by the day, concerns have been raised about the future of pumas, currently listed as a "Least Concern" species on the IUCN Red List. Thus, conservation organizations like Panthera, the global wild cat conservation organization, have pioneered efforts to protect the future of the species to ensure it does not cross the red line into the threatened category like the tigers, lions, and leopards of the world.

The Puma Program of Panthera is one of the most enterprising initiatives in this direction. Due to their elusive nature, pumas have often been misunderstood as vicious predators, fuelling their persecution by humans. With the help of scientific research into the behavior and ecology of the species, Panthera is creating a new image of these big cats as an integral component of ecosystems and landscapes in the Americas. Previously unknown behaviors of these predators are coming to light giving scientists and conservationists a better understanding of the pumas. Panthera is also keeping an eye on the population of pumas across the species' range with the help of studies like the one mentioned below.

Pumas In Trouble, Study Reveals

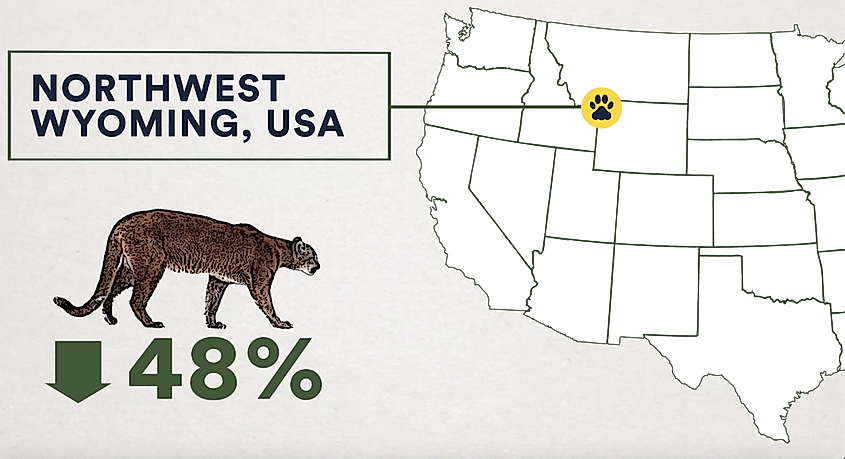

From late 2000 to 2017, a group of scientists led by Dr. Elbroch began monitoring wild pumas in the southern GYE in northwest Wyoming - a multi-use landscape. The results of the study surprised conservationists. Dr. Elbroch answered some vital questions related to the study:

Why was the study conducted?

The original objectives were to launch a new project that complimented the northern Yellowstone mountain lion project led by Toni Ruth, and which ended just as wolves were re-introduced into Yellowstone National Park. Thus, our study area was selected for two reasons—it was far enough south to get ahead of wolf recolonization (there were just 5 wolves in the system when we began) and because it was a multi-use landscape that allowed for human hunting (the northern project was for the most part in Yellowstone NP and therefore a protected area without hunting).

What are the major findings of the study? Were the results expected?

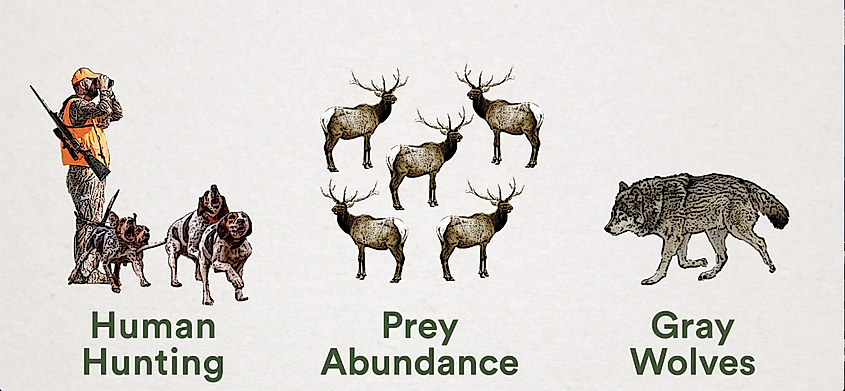

Over the course of 17 years, starting in 2000, we monitored the lives of 147 pumas across 2,300 square kilometers of northwest Wyoming, and witnessed the region’s mountain lion population decrease by 48 percent. Primarily, we sought to understand whether human hunting, declining prey availability, or recolonizing gray wolves, had the greatest impact on mountain lion survival and abundance.

And the results were indeed surprising. While mountain lions in the study area clearly molded themselves around wolves, I don’t think anyone would have predicted that wolves curbed mountain lion numbers more than human hunting.

While wolves are responsible for the decline in puma populations, is it true the other way round?

Yes, mountain lions sometimes attack and kill wolves. This seems much less frequent than wolves killing mountain lions, but it does occur, especially in areas where packs are small and the terrain favors mountain lions. In our study, we only documented a mountain lion killing one wolf—it was a roughly 6-month old wolf pup. The mountain lion was an old female called F109.

Can reintroduced wolves completely wipe out mountain lions from places where their range overlaps?

There is no reason to believe that wolves alone will drive mountain lion numbers down so low that they will wink out, but certainly, we can expect that mountain lions will exist at lower abundance where they share landscapes and prey with wolves.

In fact, we can hope that the recovery of wolves in the region will initiate greater and stronger ecosystem health in the Yellowstone Ecosystem—a resilient system in which both apex carnivores thrive.

What is the role played by human hunters in this context?

Without a doubt, hunting is among the strongest influences on both wolf and mountain lion survival, social behaviors and abundance. More than this, hunting carnivores is driven by historic cultural priorities for deer and elk we value that demonize carnivores, and prejudices built on old mythology and fear about living with large carnivores.

There is no evidence that hunting wolves supports their conservation. Some mountain lion hunting, however, does. Hound hunters, specifically, are among the most influential actors in mountain lion conservation across the West, because they are active, recognized constituents of state wildlife agencies. This is in part because the current wildlife management system generally excludes participation from non-hunters interested in mountain lion conservation. I hope, with time, we can change this system to be more equitable and inclusive.

Also, these state wildlife agencies have little contended with mountain lion populations that live with wolves. Our research highlights that mountain lion populations can decline rapidly where wolves are recovering or being reintroduced if human hunting is not simultaneously reduced to compensate for new pressures on local mountain lions.

However, since we ended this project, Wyoming has initiated wolf hunting in our study area. Wolf hunting (which aimed to remove about 12% of wolves in our core study area) shattered wolf pack dynamics and their numbers in the study system have dropped significantly. This has resulted in a redistribution of wintering elk in the study system—more of the Jackson herd is wintering in the mountains again, and without doubt this is good news for the local mountain lion population.

Does that mean wolf hunting will solve the issue?

No, the findings of our study should not be misconstrued as a scientific endorsement of the hunting of gray wolves. Instead, if we are to protect these apex carnivores whose survival is so critical to that of their ecosystems and surrounding human communities, the science clearly indicates that the way forward is to reduce or eliminate the hunting of mountain lions, or at least be very conservative where they share their homes with wolves. Our study demonstrates the interconnectedness of ecosystems and the need within the fields of conservation and wildlife management for a broader, multi-species strategy, as opposed to single-species management.