Pinnacles National Park, California

It may be the ninth and newest of California's national parks, but Pinnacles National Park has been 23 million years in the making. Forged on the back of an extinct volcano system, twisted and turned by earthquakes, pummeled by falling boulders, and refined by eons of wind and water erosion, Pinnacles has evolved into a paradoxically peaceful place. Here, visitors can hike across the undulating shrubland, delve into the talus caves, or climb high onto the very spires after which the park takes its name - all the while keeping an eye on the sky for an occasional California condor sighting. Pinnacles is already a popular getaway (especially on summer weekends), but is objectively overlooked relative to the other of California's heavy hitters. So, let's wander through the arid mountainscape, get to know the flora and fauna, and peel back the layers of history and prehistory pertaining to this centralized nature haven.

Geography

Pinnacles National Park sprawls for 26,000 acres across west-central California, just east of Salinas Valley. Its west entrance occupies a sliver of Monterey County and is a mere 12 miles removed from the city of Soledad. Its eastern portion (i.e. the more developed of the two hemispheres) belongs to San Benito County and can be reached from Hollister (the closest major city to the north) in about 40 minutes (i.e. 30 miles) via Highway 25. Because there is no through road, the quickest way to connect Highway 101 in the west with Highway 25 in the east is via King City and the Bitterwater Road (G-13) to the south.

Geological And Human History

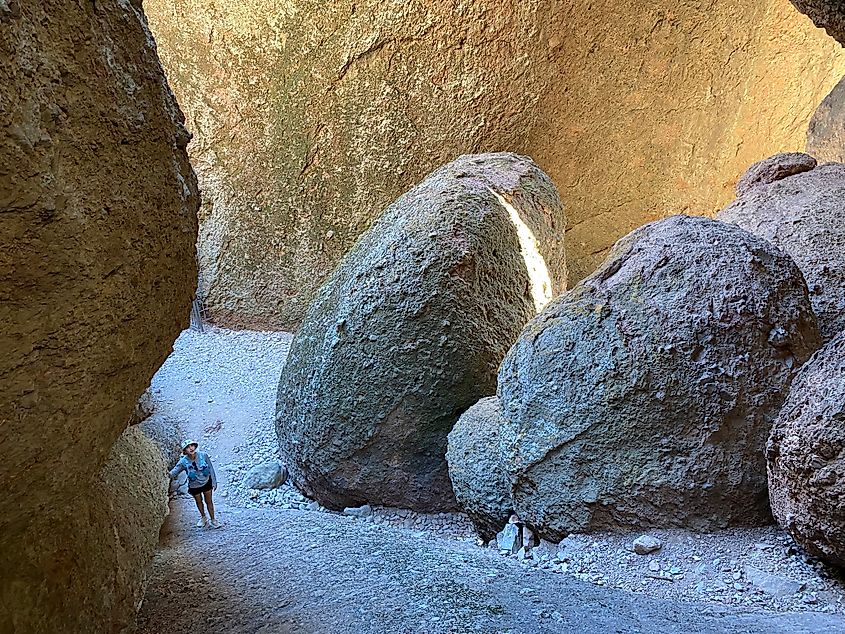

Like all great national parks, the history of what we now call Pinnacles is one of vast periods of formative natural forces followed by relatively recent human interventions. Approximately 23 million years ago (a period now known as the Pinnacles Volcanic Foundation) the San Andreas Fault caused significant seismic and volcanic activity near present-day Lancaster, California. In the process, it split the now-extinct system known as Pinnacles-Neenach Volcanic Field. Then, as it grinded against the North American Plate, the Pacific Plate carried what became the rocky backbone of the park 195 miles northwest. Once the violence abated, the everyday elements set to work with their steady chisels, eventually forming the marquee monoliths seen today. All the while, sporadic earthquakes kicked boulders down steep cliffs, where they wedged themselves rather artistically (though often precariously) in the slot canyons below - thereby giving us the talus caves that modern day visitors can grunt and climb their way through.

Evidence of human presence in the vicinity of modern day Pinnacles National Park dates back 10,000 years. These Indigenous people appear to have hunted animals and harvested plants (for the purposes of both subsistence and craftsmanship) - even evoking brush fires to increase subsequent yields. At the time of the Spanish settlers, who erected 21 Catholic Missions along El Camino Real in the late 1700s through early 1800s, the people now known as the Chalon Indians and Amah Mutsun were living in the region. Sadly, their populations were severely impacted by novel diseases. Many of the survivors were installed in the missions and converted to Christianity.

California, as a whole, was involved in tumultuous disputes through to 1847 - being tugged between Spain, Mexico, and ultimately, the United States. After the dust settled, westbound American homesteaders began to materialize in the Pinnacles region (at this point, still unnamed, and unsecured). In 1891, Schuyler Hain (aka the "Father of Pinnacles") arrived from Michigan. When he saw that people were coming to admire his backyard (so to speak), he was motivated, with the help of his ranching neighbors, the Bacon family, to preserve the land. While in the process of petitioning the public, Hain took up the helm as unofficial caretaker. Then, in 1908, the local enthusiasm was rewarded by President Theodore Roosevelt with the establishment of Pinnacles National Monument. To encourage public access, between 1933 and 1942 the Civilian Conservation Corps erected infrastructure and blazed trails through both forest and rock.

Pinnacles picked up its next conservational boost in 2013, when President Barack Obama turned the monument into a national park. At the moment, over 16,000 acres (i.e. ~65% of its total boundary) are designated as Hain Wilderness under the 1964 Wilderness Act - affording those sections with even stricter federal protections.

Of its eight older cousins in the California National Park index, Pinnacles only edges out Channel Islands in annual visitation (as of 2023). In fact, with 341,220 entries, Pinnacles National Park claimed less than a tenth of Yosemite's cumulative crowd. That said, when Irina and I visited last October, we were only able to get one weekend campsite on short notice. So people are well aware of the appeal of the pinnacles, and the attendance is probably appropriate relative to the park's capacity (more on this in a moment).

Nature

Pinnacles National Park constitutes the southern reaches of the shrub-covered Gabilan Range (itself a member of the California Coast Ranges). Beneath the rolling hills and skyward titular spires sprawl oak woodlands and blankets of chaparral, compelling canyons, and daunting, yet alluring boulder caves. Spring wildflowers brighten the landscape between March and May, while the rest of the year is graced by a soft and charming arid aesthetic.

In terms of wildlife, Pinnacles is utilized by 400 species of bees, 48 mammal species, 14 species of bats (including multiple cave colonies), eight lizards, fourteen snakes, and a turtle species to boot, and as many as 200 species of birds. During their stay, bird watchers may catalog the speedy peregrine falcon, the beloved golden eagle, and perhaps even a local favorite: the California condor. On that note, Pinnacles staff, in conjunction with the Ventana Wildlife Society have been instrumental players in the California Condor Recovery Program, which seeks to reestablish this critically-endangered raptor. Since 2003, captive-bred condors, which can grow to reach a wingspan of nine feet, have been released in the park.

Activities

The aforementioned bird watchers are well-served by Pinnacles National Park, but hikers, rock climbers, and casual campers all have a home here too. Pick up a trail map at either the East or West Visitor Center to see which of the 13 named routes (collectively covering 32 unique miles) suits your fancy and skill level. I don't think you can go wrong with any, but my personal recommendation is to take the Old Pinnacles Trail (which, by the way, if you're in a group and can work the shuttle car system,it does bridge the park's two roads) out to the Balconies Cave Trail, which can then be looped via the Balconies Cliffs Trail. This singular outing (of about 4-5 miles depending on how you slice it) shows off forest, subterranean structures, and mountain vistas.

Those with the right gear and experience can bolt into hundreds of routes up the crags and spires. There are toprope and multi-pitch options that tailor from relative beginner all the way up to beast mode. Just be aware that because of the volcanic structure, the rock here is more vulnerable than, say, the granite walls at Yosemite.

One of my favorite parts of my own visit to the park was simply kicking back at the Pinnacles Campground. Located on the east side, this is the only option for overnighting (satellite towns notwithstanding). And while there are ample RV sites, drive-in tent spots, and even a collection of tent-cabins, as I found out last fall, it doesn't hurt to reserve in advance. The fact that backcountry camping is not permitted at this time might disappoint some readers (I myself am a bit of a backcountry buff), but the light-touch community approach is still a great way to go. There is a camp store, a little public pool, nice showers, and I found the various sections to be spread out and decently secluded. Actually, just a few minutes into my morning run, I felt like the only person on the planet.

Parting Thoughts

Between the beauty of California's Pacific Coast and the magic of Joshua Tree, Pinnacles National Park made its own lasting impact during my trip across the Golden State. The hardy vegetation and expressive rocks of this centralized wilderness perfectly married those ocean and desert biomes. Better yet, Pinnacles felt like an achievable undertaking. Across a single, sunny (then starry) weekend, the trails, caves, scrambles and general bounty of the Hain Wilderness were all made available - resulting in a satiating experience, yet also, the urge to return.