What Gives Matter Mass?

In a historic discovery on July 4, 2012, scientists announced the observation of the Higgs boson, the elusive particle that grants mass to nearly all other particles. This breakthrough underpins the structure of matter that forms us and everything we see in the universe.

Physicists have discovered that matter gains its mass from a special field called the Higgs field. In the Standard Model, the electromagnetic and weak forces merge at high energies, leaving all particles massless. When this energy drops, the Higgs field "switches on," breaking the symmetry and giving particles like the W and Z bosons their mass while leaving the photon massless. Quarks and electrons also interact with this field and acquire their mass. This process is known as the Higgs mechanism. It also explains how the invisible Higgs field shapes everything around us, from atoms to entire galaxies and beyond.

Symmetries and their violation play a critical role in modern physics. A symmetry is a transformation that changes the system but keeps the observable quantities the same. The Standard Model of particle physics is a theory of many symmetries, where every part of the description admits a different kind of symmetry. While symmetries sound fundamental, perhaps one can say that their violation leads to more exciting outcomes.

In this article, we will discuss one particular pattern of symmetry breaking: that of the electroweak symmetry that governs the unification of electromagnetism and weak interactions. We will see how this phenomenon generates mass for almost all the particles we observe in the universe.

The Higgs Mechanism in the Standard Model

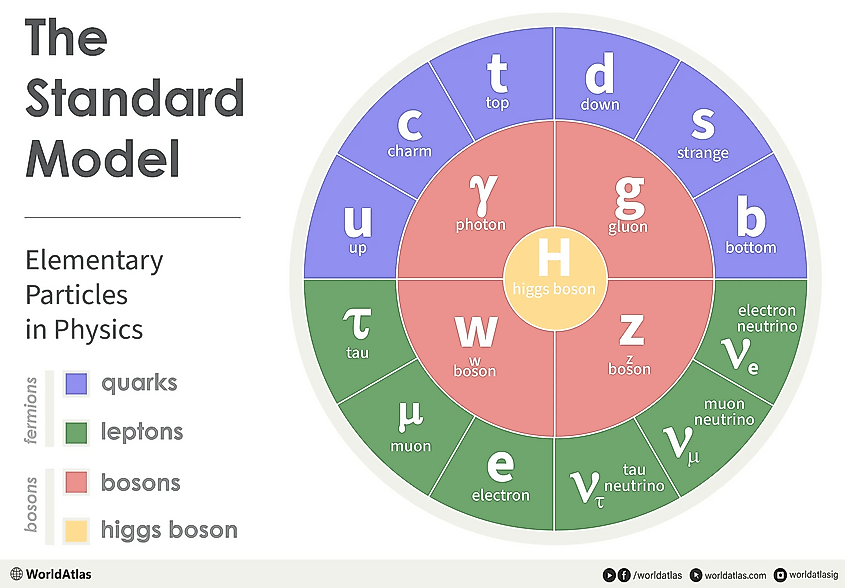

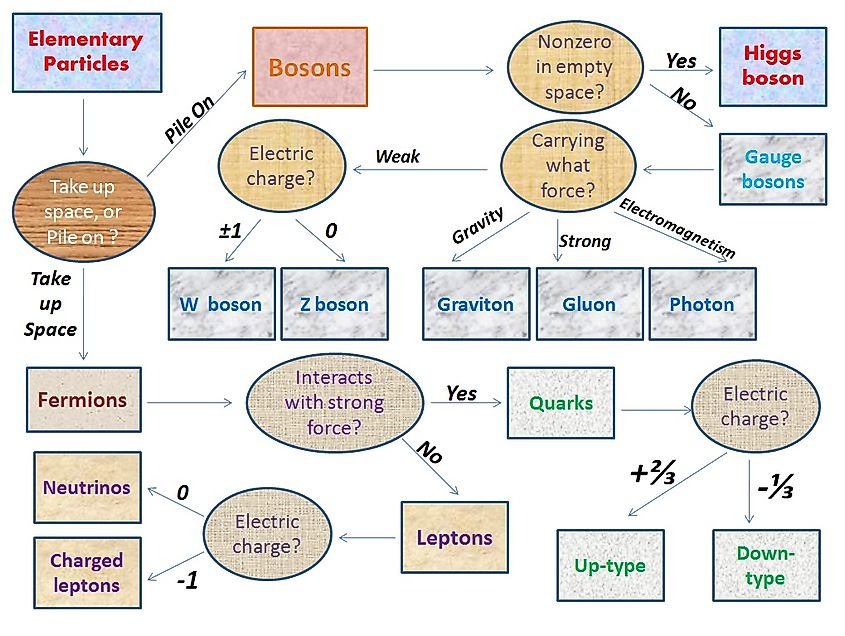

While the Standard Model was the topic of another article, it will be helpful to review some elements of it for the purpose of rendering this one self-contained. The Model describes all the fundamental particles like photons and protons and their interactions with all the forces of nature except gravity. The two most important interactions here are the electromagnetic force, which concerns charged particles and light, and the weak force, which concerns radiating objects and massive cousins of light: the W and Z bosons. The two have been shown to be two sides of the same force at sufficiently higher scales, where they become mixed into one entity: the electroweak symmetry or interaction.

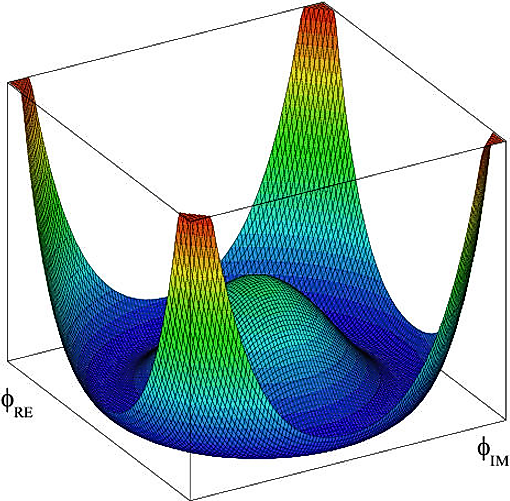

The two forces are indistinguishable above this energy scale. This means that even the W and Z bosons of the weak force have to be the same as the photon, which means they are massless. However, the masses of these bosons have been measured and experimentally verified to be non-zero. The puzzle is solved by realizing that we only measure their masses at scales below the electroweak unification scale. In other words, there must exist a mechanism that breaks the electroweak symmetry into the two sides below the unification scale.

The mechanism that gives rise to the electroweak symmetry breaking is called the Higgs mechanism, which was proposed theoretically in 1964 by three independent groups and was verified experimentally in 2012. The idea is that there is an additional particle, called the Higgs field, which is really a collection of four particles that respects the weak symmetry. It is subject to an interaction that makes its vacuum state non-trivial, breaking the symmetry. The boson then forfeits three of its constituent particles to give rise to the massive W and Z bosons. The remaining particle is what is conventionally referred to as the Higgs boson.

Mass for (almost) all

The Higgs mechanism explains how the electroweak symmetry gets broken by means of the excitations of the Higgs field, giving rise to the W and Z bosons. The question is, what does the electroweak symmetry get broken down to? The answer is just the usual electromagnetic symmetry, which explains how the photon does not gain a mass by the mechanism. For particles to gain mass by the Higgs mechanism, they need to directly interact with the Higgs field. This is true of the W and Z but not the photon, as the Higgs field is not electrically charged. Thus, we have seen that the interactions in the Standard Model dictate who gets mass or not.

The particles that we know interact with the Higgs field include quarks, which are constituents of protons and neutrons and thus all of matter, and leptons, which include electrons. The mass generated this way is proportional to how strong the interaction with the Higgs field is, so the stronger they couple, the heavier the particle. For example, the top quark is much heavier than its siblings because it strongly matches the Higgs field.

Electroweak symmetry breaking is one of the most important processes leading to the generation of mass for matter. Via the Higgs mechanism, the W and Z bosons gain mass while the photon does not, distinguishing the weak and electromagnetic forces, while fermions get mass through their interactions with the Higgs. This elegant mechanism not only unifies our understanding of two fundamental forces but also provides leverage to go beyond the Standard Model with more intricate symmetry-breaking patterns. Many mysteries in the Standard Model and Higgs physics remain, though, inviting us to further explore the fundamental nature of the universe.