Have We Explored the Ocean or Space More?

It's a common belief that humanity has explored more of outer space than its own oceans. But is this truly accurate? The comparison between ocean exploration and space exploration is more complicated than it initially seems. Understanding the difference involves examining what "exploration" really means and how deeply we've actually ventured into each domain.

Ocean Exploration

As of 2025, ocean exploration has been significant but remains surprisingly limited. While technology has rapidly advanced, allowing detailed mapping of the ocean floor, only about 25% of the ocean floor has been mapped with sonar techniques. This method provides a detailed view of the seabed's contours and geological features but still leaves three-quarters of our ocean floors largely unknown. Even more startling, human-led exploration through diving, submersibles, and remote-operated vehicles accounts for only about 5% of the ocean. These numbers demonstrate just how vast and unexplored our own planet remains beneath the waves.

Space Exploration

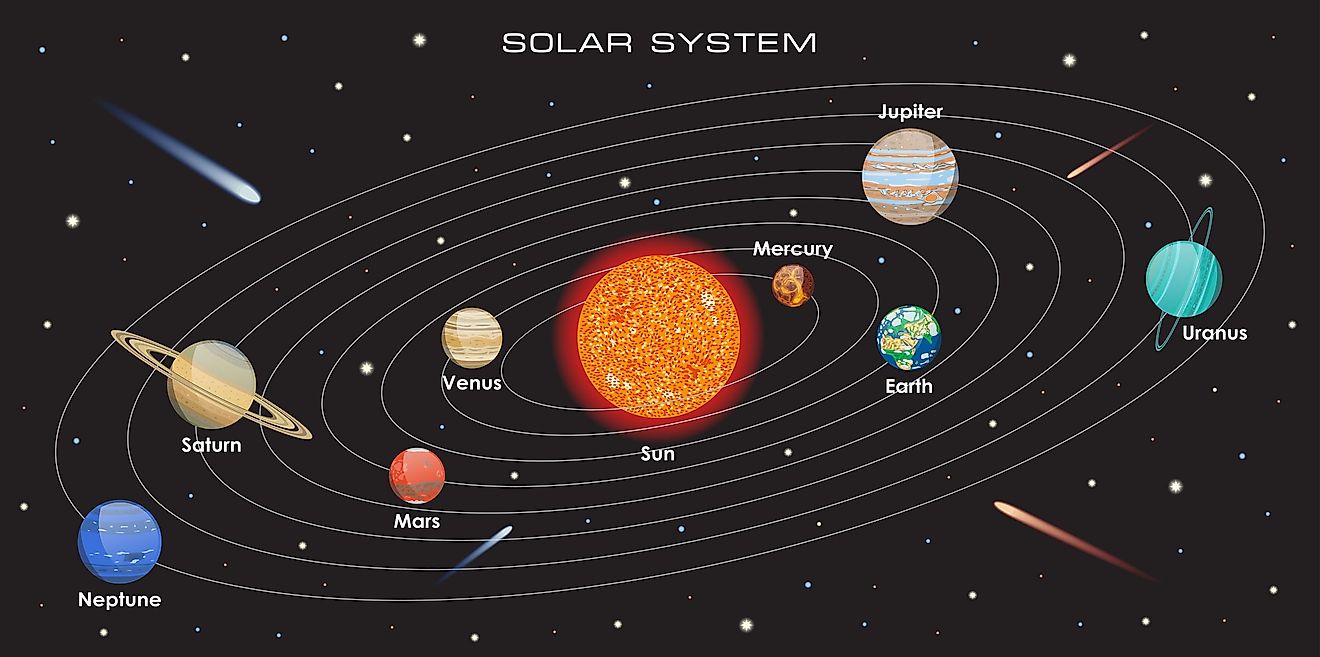

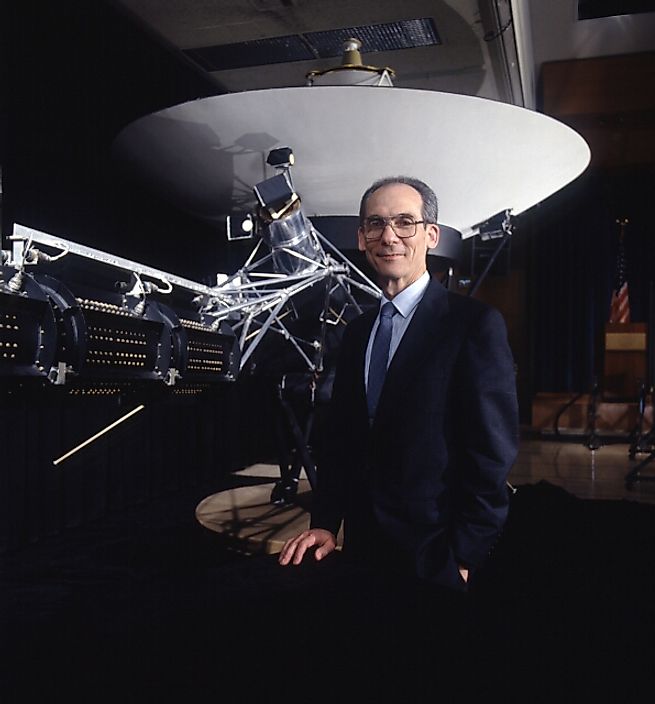

By comparison, space exploration appears to have taken humanity much further. We have built telescopes that capture stunning images of distant galaxies, stars, and planets. Our spacecraft have traversed significant distances, with Voyager 1 currently the farthest man-made object from Earth, approximately 16 billion miles away. But does this mean we have explored space more comprehensively than our oceans?

What Is Exploration?

If exploration means physically reaching and directly observing new locations, then ocean exploration clearly outpaces space. Humans have physically visited ocean depths, including the Challenger Deep, the deepest known point in Earth's oceans. This direct contact, although limited, provides tangible exploration results, including detailed observations, physical samples, and firsthand encounters with marine life.

Space exploration, meanwhile, has predominantly occurred remotely. While we've sent human missions to the Moon and robotic missions to Mars and various asteroids, our physical reach into space is remarkably small compared to the scale of the cosmos. Voyager 1’s 16 billion-mile journey is impressive in human terms but minuscule when considering the observable universe. To put it into perspective, if the observable universe were scaled down to the size of Earth, Voyager 1’s distance would equate to roughly 300 nanometers, smaller than a typical bacterium. Thus, our physical exploration of space remains incredibly limited in comparison to its immense scale.

Moreover, much of what we know about the universe comes from observational astronomy, capturing images and data from Earth or near-Earth orbit. This type of remote sensing has dramatically expanded our understanding, allowing us to catalog billions of galaxies and comprehend phenomena billions of light-years away. Yet, observing from afar is fundamentally different from physically exploring. We can see, study, and theorize about these distant worlds, but our direct exploration remains confined largely to our solar system.

In contrast, while our oceans may feel familiar because they are part of our home planet, the reality is that vast areas remain inaccessible or unexplored due to technological, financial, and logistical limitations. Even satellite imagery of Earth’s oceans, though helpful, is limited in resolution and depth penetration. We know the general shape and contours of the ocean basins, but countless ecosystems, geological formations, and biological organisms remain undiscovered. Each year, scientists discover thousands of new marine species, suggesting we have only scratched the surface of oceanic biodiversity.

Similar Challenges in Ocean and Space Exploration

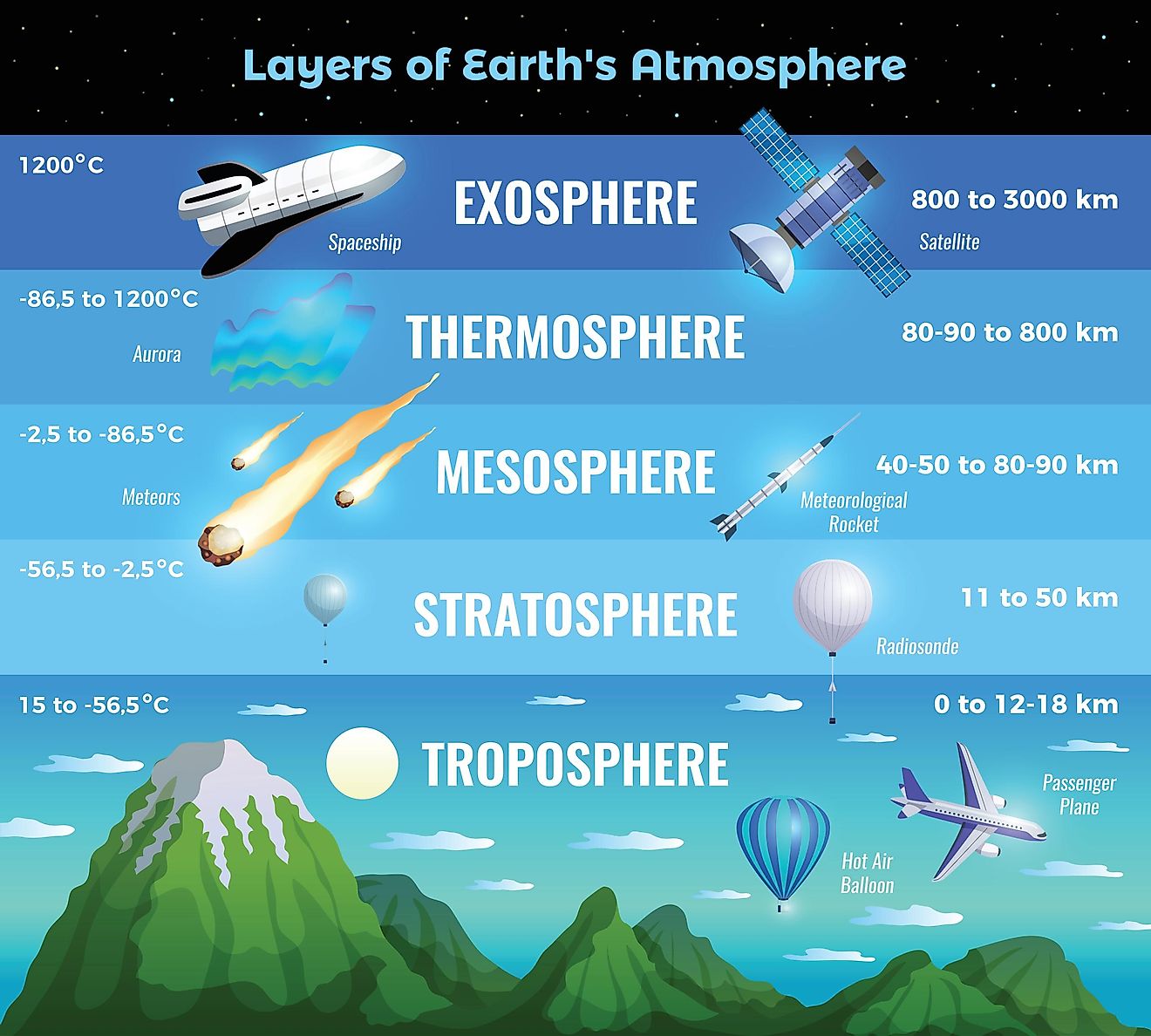

Interestingly, space and ocean exploration share many similarities in challenges. Both involve environments hostile to human life, requiring sophisticated equipment, extensive funding, and significant safety measures. The pressures experienced at deep-sea levels rival the harsh conditions encountered in space. Both fields also heavily rely on robotic or remotely operated missions due to the inherent risks and limitations of human presence.

The Verdict

Yet the perception persists that we understand space more comprehensively than our oceans. This misconception arises primarily from the extensive imagery and astronomical data available about space. Beautiful, detailed images from telescopes like Hubble and James Webb offer visually compelling evidence of deep-space exploration. Conversely, the depths of our oceans remain dark, hidden, and visually mysterious, amplifying perceptions of their unexplored nature.

If we frame exploration purely as physical, direct interaction, we have unquestionably explored more of our oceans. But if exploration is defined as a comprehensive understanding through observation and indirect study, space might appear to have the edge, given the vast volume of astronomical data we've collected. Ultimately, both definitions hold validity, underscoring the complexity of directly comparing these two frontiers.

However, considering human physical reach and tangible data, ocean exploration still surpasses space exploration. The ocean floor mapping, direct submersible dives, and collection of physical samples represent exploration in a profoundly direct way that current space exploration methods cannot yet match on a similar scale.

In conclusion, despite our incredible technological advancements, both space and ocean exploration remain largely in their infancy. We've made substantial strides in understanding both, but vast mysteries remain. While we know more about the visible universe from observation, our physical exploration of space is incredibly limited compared to the expansive direct exploration conducted in Earth's oceans. Thus, counterintuitive as it may seem, humanity has physically explored more of our oceans than space. However, the journey of discovery in both fields has barely begun, promising endless opportunities for exploration and discovery in the future.